The story of the Erasmus Huis #2: 1960-1971

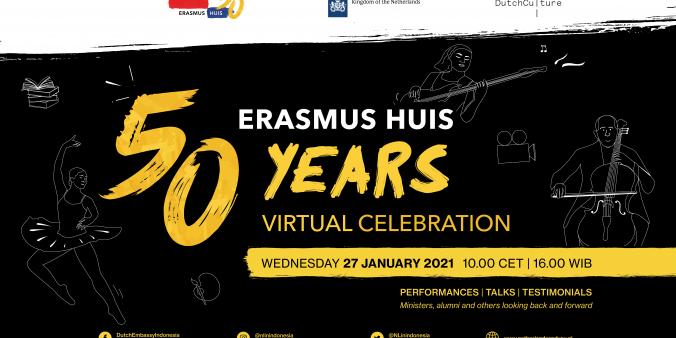

In a series of three articles, we sketch the story of Erasmus Huis, the cultural centre of the Embassy of the Netherlands in Jakarta, in the context of cultural and diplomatic interactions between Indonesia and the Netherlands. This second article covers the significant diplomatic shifts taking place in the 1960s in which the base for the current bilateral relationship was laid, and the opening of the Erasmus Huis in 1970.

“[We] hope […] for fruitful cooperation and renewed friendship with Indonesia. There are still many personal ties between the Dutch and Indonesians and in our country, there still is a wide circle of interest in the ups and downs of Indonesia”. In March 1963, Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Joseph Luns expressed his wish on national television. For a little less than three years (1960–1963) there had been no diplomatic contact between the Netherlands and Indonesia. This was considered an absolute low in the countries’ post-independence bilateral relationship. The conflict between both countries only de-escalated when the Netherlands, pressured by the United States, transferred Western New Guinea to the United Nations in August 1962, which in turn transferred the territory to Indonesia in early 1963. The air between both countries was cleared, and a process of gradual rapprochement followed. Their cultural bond was part of the glue that re-established and even helped improve the bilateral relationship, which was symbolized by the opening of the Erasmus Huis in 1970.

Small steps

In May 1963, the countries re-established diplomatic representations. But it was clear that small and cautious steps had to be taken. The Dutch diplomat Carl D. Barkman, the new charge d’affaires in Jakarta, would later describe the situation as one in which “the official attitude on both sides remained cool and expectant, not to say suspicious. Recent history had been too eventful, and too much had happened and been said, to go straight to the order of the day. There were many expressions of friendship on the personal level, but these were not yet representative of the whole” (Barkman, 1993).

Barkman and his small staff initially had to work from a couple of hotel rooms in the recently opened Hotel Indonesia. This was Jakarta’s first large hotel, located on the new Jalan Thamrin, the city’s first highway. They were both part of President Sukarno’s vision for Jakarta as a modern, global metropolis, called Lighthouse Project (Proyek Mercusuar). The High Commissioner’s Offices at Merdeka Square, along with all other diplomatic Dutch buildings, had been confiscated by the Indonesian government. Barkman was not allowed by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs to rent or buy offices or residences, because he had to wait until any of those confiscated possessions were returned.

Evidence of friendship

Barkman’s interactions with Indonesian ministers and even Sukarno were, one may say surprisingly, friendly, with a big dose of humour and often held in Dutch. Barkman noted that when establishing new ties, it made more sense for both parties to look forward rather than to look to the past. Even with regard to the very recent past, many of his interlocutors showed a remarkable realism and sporting attitude. The surprise among diplomats from other countries was therefore, according to Barkman, all the greater when gradually more evidence of friendship and respect emerged between the ex-colony and the former mother country. The increasing workload coming towards the charge d’affairs and his staff made their hotel room offices too cramped. He repeatedly diplomatically addressed the topic of housing with the Indonesian cabinet.

Eventually, Sukarno granted Barkman a residence at Jalan Diponegoro 39 in Menteng. The house was designed by Dutch architect Han Groenewegen in 1948 in the New Realism style and was previously owned by the Javasche Bank. It functioned as an office for Barkman and his staff, with consulate services in its guesthouse. Only in 1967, the Indonesian government restituted a building on Jalan Kebon Sirih 18, just south of Merdeka Square, previously owned by the Dutch State and built in 1954 as an apartment building for lower staff of the High Commissioner’s Office. It was renovated and served as the Embassy of the Netherlands for almost 15 years. The residence at Jalan Diponegoro was refurbished to become the Ambassador’s residence and has been so until today.

A new era

The capacity of the Netherlands’ Embassy in Jakarta was growing and the bilateral relationship under the new President Suharto was strengthening. Suharto had come to power in 1967 after the mass killings of 1965–1966 against the Communist Party and its (alleged) supporters, and he opened Indonesia for foreign investment and businesses to restore the country’s wrecked economy. “Indonesia has returned to the Western block”, as was said out loud in The Hague. The previous government under Sukarno had promoted an anti-foreign capital attitude under the motto of berdikari (standing on one’s own feet) (Dick, 2002).

However, the approach of Suharto’s New Order government was fundamentally different, convinced that the national economy would experience accelerated growth with the support of foreign investment. The Foreign Investment Law (UU PMA) was passed on 10 January 1967. Nevertheless, some key sectors closely linked to public necessities, such as shipping, ports, electricity, telecommunications, air travel, drinking water and railways were, and are still today, closed for foreign investment. Meanwhile, the plantation and mining sectors, which had been dominated by Dutch and Western capital during the colonial era, were once again opened to foreign investment. With the introduction of the UU PMA, many foreign companies, Dutch among them, began to re-enter Indonesia’s economy (Suryadinata, 2019; Dick, 2002).

The UU PMA opened the country’s doors to obtain support and assistance for local development programmes. Initially, Indonesia had difficulties obtaining international funding to meet its development needs. President Suharto then formed a team of economists, dubbed the ‘Berkeley Mafia’ by critics because its members were graduates of the University of California Berkeley (Suryadinata, 2019; Dick, 2002). With the basis of the ideas conveyed by these economists and the lobbying efforts by Indonesian diplomats, the Inter-Governmental Group on Indonesia (IGGI) was formed. The group involved the United States, Japan, the Netherlands, and other developed countries. IGGI was formed to provide financial assistance for Indonesia. The Netherlands was one of the IGGI’s largest contributors.

Strategic cultural cooperation

The improving relations between Indonesia and the Netherlands provided not only economic opportunities but also opportunities for cultural exchanges. The Indonesian government saw cultural cooperation as a medium to reduce political tensions and economic competition. The Dutch diplomats’ focus was expanding from political and economic matters towards cultural and educational activities. The Embassy opened small Dutch libraries in Jakarta and other Indonesian cities, which were frequently visited by academics, journalists and students.

Though other Western nations such as Australia, West Germany and Japan constructed hyper-modern embassy compounds in Jakarta’s sprawling suburbs, the Dutch stuck with their old diplomatic accommodations, as one Dutch ex-pat living in Jakarta observed in the Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant in 1967. He even referred to these buildings as “old junk”, and suggested the building of a ‘Holland House’, which could promote the Dutch business community, Dutch education and culture. In the circles of the Netherlands’ Embassy, however, the motto was that 'modesty suits us, to get work done more efficiently behind the scenes, and also considering our history'.

In his address to Dutch television back in March 1963, Minister Luns had specifically addressed the cultural aspect of the bilateral relationship, emphasizing that “knowledge of each other's culture is still widely spread. In the Netherlands, for example, there are unique treasures of knowledge and experience and very extensive documentation about Indonesia. Possibly fruitful contacts can be made on this basis in the future as well. The restoration of official relations will undoubtedly stimulate development in this direction. If the government can lend a helping hand, it will gladly consider any initiatives it deems useful, and which would also have the approval of the Indonesian government”. This attitude would materialize when Minister Luns and the Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Adam Malik, signed the agreement on cultural cooperation on 7 July 1968.

The first cultural collaboration materialized just one month after the agreement was signed. Kompas, a leading Indonesian newspaper, reported in 1968 that the Dutch government had donated an information bus to Indonesia as part of a government project for illiteracy eradication. To operate the vehicle, “Indonesia has sent four people to get training in the Netherlands”. In 1969, cooperation increased. On 26 April that year, then-Dutch ambassador to Indonesia Hugo Scheltema inaugurated the Indonesian Graphic Centre in Jakarta, the institution that was established to continue the illiteracy eradication project and specifically aimed at improving the quality of Indonesian publishing.

Opening of Erasmus Huis

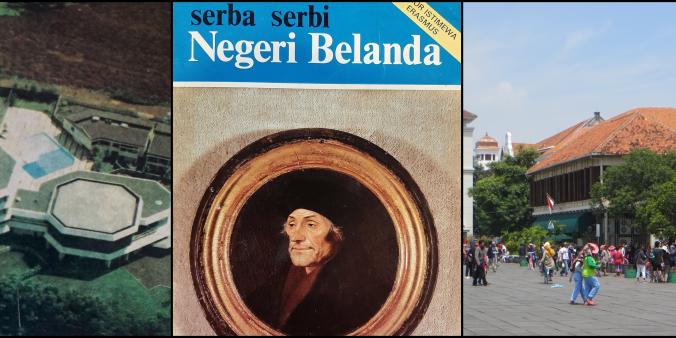

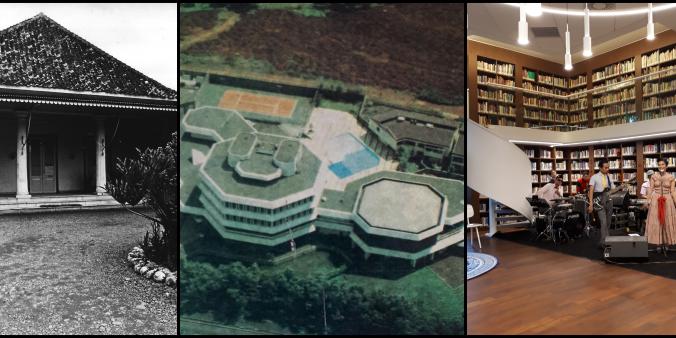

On 27 March 1970 the new cultural centre of the Netherlands Embassy, called Erasmus Huis, opened its doors in a modest colonial residential house on Jalan Menteng Raya 25, just southeast of Merdeka Square, close to the new Embassy on Jalan Kebon Sirih. The cultural centre was named after the Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who examined the world, according to ambassador Scheltema, “always maintaining a moderate attitude, sound mind and appreciating human order of all ages and every social association”, which he considered fitting regarding the open attitude of Indonesian people. The opening was performed by Prince Bernard, the husband of Queen Juliana, who was in Indonesia at the time for a semi-official visit.

According to the Dutch newspaper De Waarheid the visit was approved by the Dutch cabinet, and could be regarded as a trial run for the, then still denied upcoming official state visit by the Queen and Prince to Indonesia a year later. Another Dutch media outlet, Vrij Nederland, refers to the Prince as “Holland’s best salesman”, commenting that “the goodwill which the prince […] acquired in official Indonesia will not be unwelcome to the Dutch business community”.

The Erasmus Huis, which was the expansion of a small reading room opened a few years earlier in the same location, was intended as “a meeting centre for Indonesian and Dutch people and to give Indonesian fans the opportunity to learn about Dutch culture”. It offered books, gramophone records, newspapers and magazines. There were daily film and documentary screenings, regular lectures and music and cabaret performances. To borrow books, those interested could become a member, with the number of members growing from 1.000 in 1969 to 4.000 in 1971.

The Erasmus Huis’ first director, Cyriel van Dijk, was charged with expanding the centre’s programming, including inviting both Dutch and Indonesian artists to perform together at Erasmus Huis. In an exchange with a Member of Parliament in May 1971, Minister Luns informed that the Erasmus Huis at the time was not the only Dutch culture centre in Indonesia, listing major cultural centres in Bandung and Yogyakarta, and a new reading room in Makassar, whereas new reading rooms in Surabaya, Medan, Manado and Semarang are planned. In these venues, Dutch literature was provided, and Dutch language classes were taught.

New enthusiasm and new relationships

In August 1971, Queen Juliana and Prince Bernard visited Indonesia on the first state visit by a Dutch head of state to the Indonesian archipelago. It seems hard to believe, but the only Dutch royal who ever visited the Dutch East Indies was Prince Henry ‘the Navigator’ (Hendrik 'de Zeevaarder’), the third son of King Willem II and Anna Paulowna, as part of his naval education in 1837. Queen Juliana and Prince Bernard’s 12-day state visit was perceived as a huge success, and everywhere the royal couple went they were met with large crowds of enthusiastically smiling people waving Indonesian and Dutch flags.

In the Indonesian newspaper Abadi, Mohammad Roem, a former Interior Minister, shared his observations of the arrival of the royal couple, revealing that never before a foreign head of state had received such a lively welcome, as if they were long-time acquaintances. Roem also described himself as a son of the colonial era. In his mind, the royal visit caused a lot of reflection. When the Dutch national anthem, the Wilhelmus, was played, elderly Indonesians present recognized it instantly, as it had been the national anthem of the Dutch East Indies: as such it did not feel like the anthem of a foreign country, Roem stated. “Because we had known the Wilhelmus since our childhood, we sang along in our hearts, now with a sincere heart”, because Indonesia and the Netherlands were now equal nations.

During a banquet at the Merdeka Palace, President Suharto reflected on the Dutch-Indonesian relationship: “Remembering past history often makes people emotional. However, the ability to reassess past history also often gives new strengths to build a future with a new face. Our two nations are actually filling this new era with new enthusiasm and new relationships”. Queen Juliana returned during the same banquet that “I see the profound wisdom of your older culture as a valuable complement to the passion of our Western movement […] I believe that we from these complementary contradictions can learn to understand, and even receive many good things from each other. Thus, we think of each other more broadly, in beneficial influences, without exaggerating our own character”. During a visit to the University of Indonesia campus, she addressed the assembled students, saying that “You, the young ones, have played an important role in Indonesia’s history and will play an important role in its future as well”.

Roem also attended the banquet. He sat next to the commander of the Greater Jakarta regional police, Widodo Budidarmo, and asked if there were any difficulties the police had faced while securing the royal visit. Budidarmo then replied that there had not been any incidents. There was no group of people, however small, who did not congratulate the visit of Queen Juliana, he said (Roem, 1997). Perhaps, this proved the assessment of a renowned Indonesian historian, Ong Hok Ham, who stated that “Indonesian people may hate the colonial government, but they respect the queen”. Living in the transition from the colonial period to the independence period, Ong himself once said that the only Dutch person his family respected was the Queen of the Netherlands (Ong Hok Ham, 1989).

Former Batavia as cultural heritage area

Earlier in 1971, the governor of Jakarta, Ali Sadikin, announced his plans to restore the city’s historical inner city, Kota Tua, to attract tourists. Kompas conveyed that the Jakarta government decided to use the 18th century as a reference for the restoration because the government held the most complete historical sources on 18th-century Jakarta. The restoration effort was said to have received a good response from the public, both at home and abroad because Sadikin was known for his persistence even outside of Indonesia.

In the memories of Jakarta’s older generation, this governor occupies a special place. Sujono, a 78-year-old Jakarta resident who was interviewed by the research team at the University of Indonesia campus in 2022, said that Sadikin arguably was the best governor of Jakarta and that the programmes he initiated, such as the restoration of Kota Tua, had proven to be beneficial for Jakarta residents to this day. He added that Sadikin has laid the foundation for Kota Tua to become an icon of Jakarta and that it has become an important tourist destination: “Today, who does not know Jakarta’s Kota Tua?”

According to NRC Handelsblad, the restoration was to be led by the American UN advisor Sergio Dello Strologo, and the restoration costs estimated at 2.5 million dollars would be contributed by American, English, and Dutch businesses with interests in Indonesia. Also, the Rockefeller Foundation and World Bank were mentioned as potential investors. The newspaper also announced that Governor Sadikin wants to lay a wooden replica of a Dutch East Indies Company ship in Kali Besar (the area’s main canal) and that he wanted to give a less attractive building on the former town hall square a historic camouflage façade. “It does remind of Disneyland, but in which country have no compromises of what is historically valuable been made between tourism and restoration?”

According to the Limburgsch Dagblad, an Indonesian newspaper wrote about the restoration efforts: “Our country is independent and sovereign. We are able to look back on these things as part of our history. That is all. Out of sheer curiosity, it is just fun to breathe new life into this piece of history”. In 1976, Dutch journalist and historian Paul van ‘t Veer observed in Het Parool that the old 17th-century city hall with its surroundings had been restored as a Dutch museum, adding that for most Indonesians, that time lies in a grey past. “Yet I have spoken to a lot of young people who had no idea that there had ever been such a thing as a Dutch time,” he continued. Those same young people, as addressed by Queen Juliana as representatives of the future of their country, are key for sustaining the relationship between Indonesia and the Netherlands. For this reason, they were, and still are, an increasingly important target group for the Erasmus Huis.

With the signing of the agreement on cultural cooperation in 1968, the opening of the Erasmus Huis in 1970, the state visit by Queen Juliana and the restoration efforts in Kota Tua in 1971, the bilateral relationship between Indonesia and the Netherlands received a new boost with a strong cultural character. The colonial past, during the first years of independence under Sukarno an obvious cause for conflict, became a fertile ground for future collaboration during the Suharto regime.

The story of the Erasmus Huis #1: 1945-1960

The story of the Erasmus Huis #3: 1970-present

This article has also been published in Indonesian on Historia.id. You can find this article here.

Sources and further reading

Barkman, C.D. Bestemming Jakarta: het herstel der Nederlands-Indonesische betrekkingen. Amsterdam: Van Soeren, 1993.

Blackburn, Susan. Jakarta Sejarah 400 Tahun. Jakarta: Masup, 2011.

Dick, Howard (et.al). The Emergence of a National Economy: An Economic History of Indonesia, 1800-2000. Cross Nest NSW, Australia: Allen and Unwin, 2002.

Hanna, Willard A. Hikayat Jakarta. Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia, 1988.

K.H., Ramadhan. Ali Sadikin, Membenahi Jakarta Menjadi Kota yang Manusiawi. Jakarta: Ufuk Press, 2012.

Kanumoyoso, Bondan. Nasionalisasi Peusahaan Belanda di Indonesia. Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan, 2001.

Leifer, Michael. Politik Luar Negeri Indonesia. Jakarta: Gramedia, 1986.

Malik, Adam. Sepuluh Tahun Politik Luar Negeri Orde Baru. Jakarta: Yayasan Idayu, 1976.

Ong Hok Ham. Runtuhnya Hindia Belanda. Jakarta: Gramedia, 1989.

Suryadinata, Leo. Politik Luar Negeri Indonesia di Bawah Suharto. Jakarta, LP3ES, 2019.

Wie, Thee Kian. Industrialisasi di Indonesia. Jakarta: LP3ES, 1994.