Resilience, creativity and solidarity – Recap of Infected Cities #14: Madrid

On 21 January 2021, artists and professionals from different backgrounds connected through Zoom for a conversation from Pakhuis de Zwijger led by moderator Georgios Lazakis, joined by journalist Maartje Bakker. From Madrid, the participants reflected on the impact of the COVID crisis, the resilience, creativity and solidarity of the Madrilenians, and how the cultural sector is moving forward. (video below)

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, Spain was one of the hardest-hit countries in Europe, with Madrid as the epicentre of infections. The capital of Spain has more than 3 million inhabitants, and its surrounding Community of Madrid over 6 million, making it one of the largest cities in Europe. To date, there have been almost 3 million registered COVID-19 cases nationwide, and over half a million in Madrid alone. Here, nearly 13,000 people have died since the beginning of the pandemic, the highest number within Spain.

After three months of one of the world’s most stringent lockdowns, the country enjoyed a rapid reopening over the summer, but it has since struggled to contain a second wave of infection. In October, a new national state of emergency was declared. Spain is one of the EU member states most affected by the economic fallout from the pandemic. With Madrid not only the political and economic centre of Spain but also the cultural and artistic heart of the country, what are the consequences of this crisis? What is the role of culture in this unprecedented situation and what innovative projects have artists and cultural institutions initiated in the capital? Professionals from different art disciplines discussed their hardships and inspirations, and how they can create hope, connection, empowerment and solidarity.

Hunger queues

At the beginning of the debate, a clip was shown of La Gran Fila (The Big Line), a video shot in Madrid last May and June by Spanish artist Santiago Sierra. The black and white film slowly and silently moves past a line, counting more than 800 people, who are standing in a so-called colas del hambre, or hunger queues.

Maartje Bakker, who just returned to the Netherlands from Madrid, where she lived and worked for five years as a correspondent for Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant says she's familiar with the phenomenon of the hunger queues. “It is one of the most striking visible impacts of the economic crisis. There are many people with irregular jobs, who don't have any social security. If they cannot go to work, they lose their jobs and immediately find themselves without any income. Now, for the first time in their lives, they find themselves without enough money to buy even staple ingredients like rice and potatoes. The film shows them lining up for food, without showing their faces, which is a very interesting perspective. In a way, it represents their sense of shame for being there.”

Photographer Carmenchu Alemán was in Pamplona at the time of the first lockdown, and upon her return to Madrid felt shocked by what she saw. “Madrid is such a vibrant city. I live in the city centre, just off the Puerto del Sol square, and there are always hundreds of thousands of people around. But when I saw how empty the streets were, I couldn’t believe my eyes. The city felt like a shadow of its former self, and its silence hurt me. I had to go out every day with my camera. It was as if the city was calling me: the windows and the walls…”

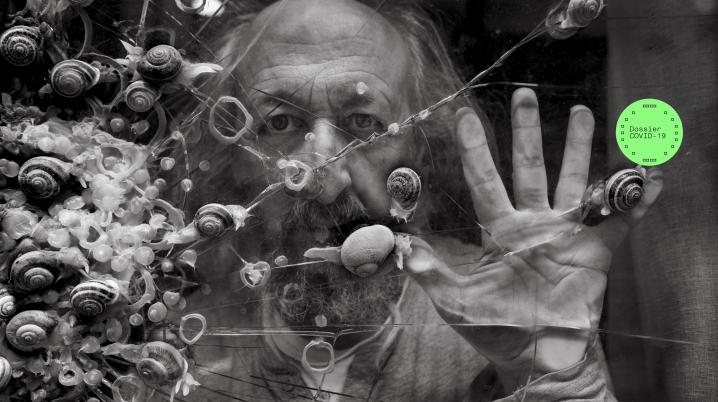

The result was a collection of photographs shot during the lockdown, called Stop Madrid. Alemán recalls: “The first picture I took was on 14 March 2020. I saw a window full of snails and when I peered inside, I saw a man. He came up to the glass and spoke with me through it, explaining that he didn't have enough money to fix the broken window, so he decided to just glue it with silicon. It was so horrifying – the glue and the snails – that to me it was symbolic of the situation and how we all felt during those days. We were all like snails glued to a window, trying to escape. Another one of my pictures shows a couple collapsed on the ground, talking on the phone. I took this picture outside the train station, where they had just received a call that her mother had died of COVID. There were all these terrible scenes playing out, not just in the hospitals, but even on the streets.”

Thriving in the face of difficulty

Video artist, installation artist and sculptor Fernando Sánchez Castillo feels there is a fine line between showing the atrocities of the pandemic for artistic purposes and for sensation. His work is an attempt to rewrite history’s accounts, or at least to raise awareness about its complexities and traces, and to show that it is constructed from many positions of power. “As artists, we need to be critical and sensitive to people’s pain,” he says. “Some things are simply too real and too cruel, and we don’t want to turn them into a kind of pornography. But at the same time, we have a duty not to forget. There is still a lot of work to be done. On the upside, because of the events in 2020 and 2021, our lives have become very introspective. We have had to deal with an economic crisis, we were faced by an invisible enemy and risked losing our lives. We’ve had a lot of time to use our minds and to use culture as a positive tool. This has helped us to stay alive.”

Inmaculada Ballesteros is the director of the Observatory for Culture and Communication of thinktank Fundación Alternativas, an organisation that follows the evolution of inequality in Spain, publishing reports on topics including culture and inequality. “COVID-19 has brought issues in our society to the surface,” Ballesteros says. “In Madrid, many people are balancing on the edge of poverty and this pandemic has made it more visible. The work of artists like Santiago Sierra helps us to face the reality. This project is also characteristic of people working in the cultural sector, which has been hit hard by the pandemic. And yet, it has shown resilience and creativity largely thanks to generous creators and companies working for free. Some are making good use of the digital environment and even thriving in the face of difficulty, like small bookshops. At the beginning of the crisis they suffered terribly, but then they decided to create their own platform with 800 booksellers in Madrid joining forces. This has become incredibly successful.”

Solidarity

Laura Fernández of Medialab Prado agrees that the solidarity amongst Madrilenians is one of the most positive aspects of the COVID crisis. Medialab Prado is a citizen laboratory for the production, research and dissemination of cultural projects. It explores forms of experimentation and collaborative learning that have emerged with digital networks. Fernández explains that they are being used to working face-to-face and taking advantage of encounters in the physical space to activate collaborative processes. "Of course we are unable to organise face-to-face encounters now," she says, "so we had to come up with something new. During the first weeks of the lockdown, we joined forces with other initiatives in Spain in the same situation. Together, we worked on a digital platform where different local initiatives could connect with one another. An interactive map was created using Ushahidi: software originally developed in Kenya and used worldwide to help support people during catastrophes. The map was made by citizens and for citizens, to ask for or offer help. Simple things, like going out to buy food or get medicine for your neighbour who is frightened of the virus.”

At Teatro de La Abadía, artistic coordinator Ronald Brouwer believes some creative alternatives are here to stay: “The essence of theatre, of course, is performing live in front of an audience. During the months of lockdown, we had to close the theatre for thirteen weeks. We ended up going online, to perform via Zoom, and in the end, invented a way of doing something that comes very close to real theatre. All in all, we put on ten different performances: some of them a monologue of an actor reciting Lorca texts to the camera or a play by Simon Stephens, others tailor-made for this medium, making use of the ability to share images, share the screen, live commenting in chats so that the audience could interact with the performers. Our theatre reopened in September with reduced seat capacity, so we are able to hold performances again. But these new languages have helped us connect with a brand-new audience, and the theatre is now in a process of transformation. It’s a positive development.”

With Madrid and other cities around the world slowly opening up again, most people are breathing a sigh of relief at the prospect of a return to normalcy. But some feel that there have been positive changes, and the lessons learned during the pandemic are not to be forgotten.

Maartje Bakker: “Of course the lockdown has been incredibly difficult, but there were beautiful aspects to it as well. Less noise and less pollution. People took to the streets with their bikes and cycled down main roads in the centre of town, which are normally filled with cars. There have been wonderful initiatives of solidarity, with so many people helping each other. The pandemic has forced us to break from our routines and reinvent ourselves – both on a personal level and in the cultural sector. This fills me with happiness because it proves that even in the most difficult times there can be beautiful ideas. Creativity has brought a spark of light to a really dark time.”

If you are a cultural professional interested in an international collaboration with Spain, feel free to contact our Focal Countries Desk.