'They call me babu': giving a voice to untold stories

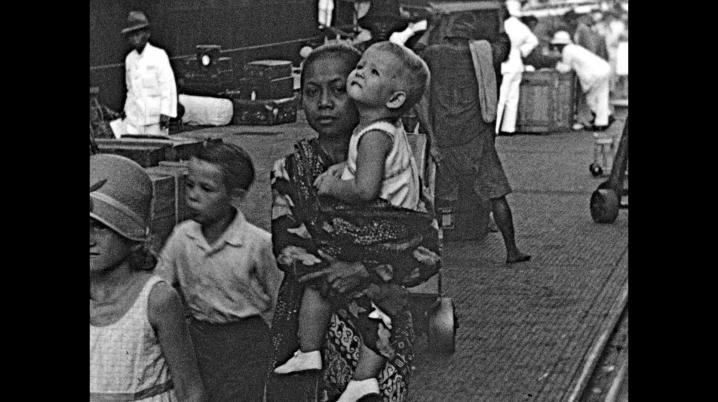

They call me babu (or Ze noemen me baboe) is the story of the Javanese Alima, the babu of a Dutch family in the former Dutch East Indies. Babu was the word used by Dutch families to refer to their Indonesian nannies during Dutch colonial rule. Their real names, as well as their stories, are still often unknown.

The director Sandra Beerends depicts Alima’s story through archival footage, while Alima, the narrator, tells her stories to her deceased mother. Alima’s story coincides with the turbulent period between 1939 and 1949, that witnessed WWII, the Japanese occupation of the former Dutch East Indies and the Indonesian stride for independence from the Netherlands. In this rapidly changing world, Alima’s story is one of courage, conflicting loyalties, and new hopes.

Anticipating the première of the documentary, we recently interviewed Sandra Beerends to learn more about this historically and emotionally charged documentary.

What inspired you to make a documentary about the figure of the babu?

"I have a Dutch-Indonesian background, my father is Dutch and my mother was born in the former Dutch East Indies. When I was growing up, she used to tell me many stories about her childhood, amongst which about her "babu". And about how from the moment she woke up until she went to bed, the babu was always there to take care of her. When I became a bit older, I realised that many people I knew that had been brought up in the former Dutch East Indies, had heart-warming stories about their babus.

Most of these stories stopped with WWII, when many Dutch people were interned in camps during the Japanese occupation and many ended up returning or going to the Netherlands for the first time. After these events, many of the families weren’t able to reconnect to their babus; not only because of the politically complicated situation, but also because they never knew their babu’s real name.

This made me realise something about their position – although they were cherished by the Dutch families (and especially the children), they weren’t an equal part of the family. In a sense, they were invisible. And considering the lack of information about them – with the exception of the memories of Dutch families – their stories continue to be invisible today. That’s why I wanted to tell the story of the babus, for those families who lost contact with them, but especially because I wanted to know what happened to them after the independence of Indonesia and after the (often) forced farewells. I also wanted to know how they had experienced this time shared with Dutch families. I wanted to try and tell the Indonesian side – their side – of the stories."

What was your starting point when searching for stories of the babus?

"My starting point was archival research. More specifically, I started with amateur film materials from different families that were kept at the EYE Film Museum. Many films were made by Dutch families in the Dutch East Indies, since they wanted to show to their families and friends in the Netherlands what their lives were like there. I hoped that through these films I would be able find out more about the babus. But I soon realised that that wasn’t the case. Often the films barely showed the babus or they were completely absent, since they’re weren’t the focus of the film.

Altogether I watched 500 films, 179 of which are partly shown in the documentary. Besides the amateur family films, I also used other sources, such as films made by Dutch factories, anthropological film materials and Dutch, Indonesian and Japanese political propaganda footage. This means that the films used, sometimes just for just a few seconds, present very different angles. And they came from different archives, including the NHK Archives (Japan) and Beeld en Geluid (the Netherlands). A lot of the materials I used were organised and digitalised in the context of this project, which means that they are now more easily accessible to others."

What other sources did you use?

"To complement the archival materials, I carried out interviews with many people in the Netherlands who had a babu during their childhood, growing up in the former Dutch East Indies. And also with the children and the grandchildren of former babus, who stayed in the Netherlands after the war. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, I was able to find testimonies of former babus, collected in the context of various oral history projects carried out from a sociological perspective.

I also travelled to Indonesia to try and find former babus whom I could talk to, based on information provided to me in the Netherlands. With a lot of effort, and the support of an Indonesian guide, her driver and many helpful neighbours, I was able to find two former babus in Bandung and a woman in Surabaya who was coordinating an oral history project amongst former babus. They told me a lot about their experiences as babus, but also about historical events at the time. As much as possible, I used these oral histories to inform the narrative of the documentary."

Who is Alima?

"Alima, the narrator of the documentary, is a fictional character. But almost all the stories she tells, and the feelings, thoughts, doubts, fears and hopes she shares with her mother, were based on first and second hand accounts of former babus and of Dutch family members. In this sense, Alima gives a name and a voice to the many women who worked for Dutch families in the context of the former Dutch East Indies.

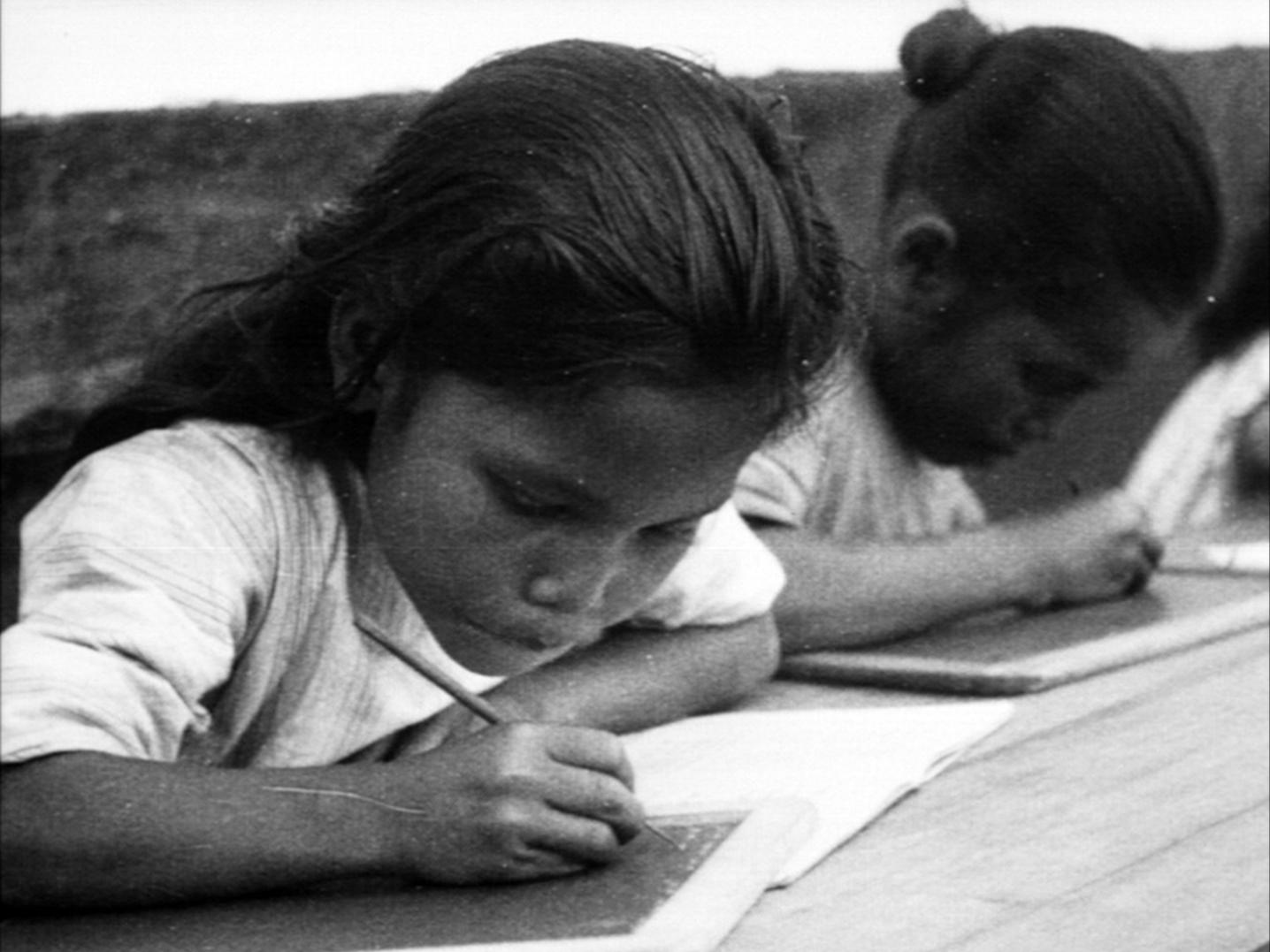

Alima – or rather, the many Alimas – were extremely brave women. I learnt about how some babus would travel to the Netherlands with their Dutch families, a country whose language they didn’t speak, whose weather they weren’t familiar with, and they fought hard to adapt. I heard one story of a former babu who, having had the chance to learn how to read and write in the Netherlands, upon returning to Indonesia and after independence, decided to strive to ensure that other girls would have access to education like she had."

What did you learn in the process of creating this documentary?

"I was quite surprised to learn that for the women whose testimonials I read or collected, the 'Dutch period' (as they called it) was seen in a relatively positive light, since for them working for Dutch families meant living stability and security; unlike the 'Japanese period' (as it was called), a time of war during which they often didn’t have work. I also realised that many babus had struggled with a loyalty conflict, since they felt part of the Dutch family for whom they worked, but at the same time they were not, and this became clear with all the (political) changes between 1939 and 1949. For the Japanese during WWII, the Dutch were the enemy and the Indonesians were Asian, therefore they didn’t understand the babus who wanted to visit and help the Dutch families in the Japanese camps. In doing, they too became the enemy.

After the Japanese capitulation and the Indonesian proclamation of independence (17 August 1945), there were violent actions from Indonesian independence fighters against the Dutch (known as Bersiap). And during the Dutch 'Politionele Acties', the violent actions carried out by the Dutch to regain their colony, the babus’ former Dutch employers became the military enemies of the Indonesian people. These actions (carried out between 1945 and 1949) are known in Indonesia as Agresi Militer Belanda (or Military Aggression from the Dutch). And the period is called by Indonesians 'the revolution' or 'independence war'. I thought that the use of the different terms for the different periods was very interesting, as it revealed something about the babus’ perspectives on these developments.

Another important thing I learnt was that the stories of the babus were often also stories of emancipation, of finding their own space and their role in a changing world – the world of independent Indonesia. By focusing on people – and a specific group of people – rather than the wider historical events, I was able to gain a better understanding of this difficult period of time. I realised that different people experienced this period in very different, personal ways. They call me babu is really a story about the human side of this period of time."

'They call me babu' will be premiered during IDFA (20 November – 1 December 2019) on Saturday 23 November at Eye. It will be shown at several cinemas in the Netherlands from 28 November 2019 onwards. The production team is working on making the release of the documentary also possible in Indonesia.

This project was supported by the Shared Cultural Heritage Matching Fund of DutchCulture.

All images courtesy of Pieter van Huystee Film.

Update:

'They Call Me Babu' wins the Special Mention Award at the Jakarta Independent Film Festival 2021, which showcases stories of different genres, styles, and from different countries to capture the imagination, talent, and diversity of independent filmmakers. This Special Mention Award is a recognition of having met the highest standard of excellence.