Brazilian film industry: Current situation and prospects

Our cinema is not young because of our age (...) [but] because Brazilian Man is young; Brazil's problems are new; our light is new – so from the outset our films are quite unlike European cinema. GLAUBER ROCHA

Brazil is a country of superlatives: the world's 5th largest land area, 7th largest gross domestic product, and 5th largest population, with over 200 million. Its numerical magnitude is reflected in its culture. In his inaugural speech as Minister of Culture in January 2003, Gilberto Gil said:

“(...) Brazilian cultural multiplicity is a reality. (...). If there are two aspects of Brazil today that irresistibly attract international interest, intelligence and sensitivity, one is the Amazon with its biodiversity – and the other is Brazilian culture, with its semio-diversity. ”

Music, the visual arts, theatre, dance, expressions of traditional culture, and many other forms of artistic expression thrive in all five regions, and cinema is no exception. Expressive works, wealth of talent and large-scale market integrate the whole we call Brazilian Cinema. Writing about this sector poses complex issues in both symbolic and economical terms that will be merely outlined in the following discussion.

Brief history of our cinema

Moving images were first projected in the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1896. As Brazil's federal capital at that time, Rio's downtown area boasted a proliferation of exhibition venues with inventions auguring the early days of cinema. “Cinematography was just one of several paid amusements brought to Rio de Janeiro by foreign visitors.”

The history of cinema's early period in Brazil is still disputed despite progress made in terms of systematically arranging and analysing data. Brazilian cinema's much-vaunted belle époque may well have actually happened in Rio de Janeiro, but nothing remains to be seen today and further research has yet to come up with any conclusions. The fact is that, even in the early 20th century, Brazil's fluctuating output had to compete with imported foreign films and was unable to so on an equal footing. Filmmaking and exhibition centred mainly in the city of Rio de Janeiro, while the city of São Paulo was only beginning to build up its economic clout with the bare outlines of a certain level of cinema activity.

Outside of Rio and São Paulo, filmmaking spread to other locations from 1925 onwards. There were regional cycles in a number of cities such as Recife (Pernambuco), Pelotas (Rio Grande do Sul) and Cataguases (Minas Gerais). The latter produced one of Brazilian cinema's most significant directors: Humberto Mauro, who was actively involved making classic Brazilian silent films such as Tesouro perdido (Lost Treasure) (1926) and Sangue mineiro (Blood of Minas Gerais) (1929), followed by a fruitful series that provided some of the major points of reference for the Cinema Novo movement, as discussed below. Mauro was one of several leading figures emerging at that time who would continue to make films in the next period. This was also the case of the actress, director and producer Carmen Santos, who later joined Adhemar Gonzaga, who in his turn became part of the history of our cinema with the founding of Cinédia Studios, in 1930.

The 1930s, 40s and 50s were the heyday of one of Brazilian cinema’s most popular genres, the chanchada, a comedy of manners satirizing everyday-life and often featuring carnival-related settings with musical performances. Chanchadas eventually engaged in an important dialogue with viewers. The Rio de Janeiro film studios Cinédia, founded by Gonzaga, and Atlântida Cinematográfica founded by Moacir Fenelon and José Carlos Burle in 1941, left their footprint on the period with countless hits that are still significant points of reference today. Many talents migrated from radio stations and theatre stages to cinema through these films. One of the great discoveries of the period was Carmen Miranda, whose first film was made by Cinédia.

Atlântida in turn joined forces with Luiz Severiano Ribeiro Jr., one of Brazil's leading exhibitors to verticalize production and make box-office hits. While mirroring the American studios' production model, his comedies parodied Hollywood too. Nem Sansão nem Dalila (Neither Samson nor Delilah) and Matar ou Correr [Kill or Run Away] were parodies of their U.S. originals, Samson and Delilah and High Noon. Some of his characters that became highly popular and are still seen as major icons of our cinema included the remarkable duo Oscarito and Grande Otelo featured in a series of films.

In the 1950s, a number of tentative film-industry ventures emerged in São Paulo. Foremost among them were the Companhia de Cinema Vera Cruz and Companhia Maristela studios, which invested heavily in infrastructure, equipment and foreign technical and artistic talent needed to continually roll out films that would meet the industry’s standards internationally. Vera Cruz and Maristela employed many Brazilian talents, such as the directors Anselmo Duarte and Lima Barreto, and the actor Cacilda Becker. Vera Cruz cast Amácio Mazzaropi in his first role at the beginning of his film career. In the following decades, his Jeca Tatu hillbilly character was immortalized in a series of hits that he himself produced. However, the industry's ambition was soon to be dented by box-office numbers that could not sustain this production model, so the major local studios were wound up.

Much criticized by other Brazilian filmmakers who had avoided this business model, the cinema of the 1950's also prompted a period of heated debate. Critic and director Alex Viany posed important questions concerning the aesthetics of this imported "industrial" filmmaking. In the context of the 1950s, a film that set a new pointer for Brazilian Cinema and its future was Rio 40 Graus (Rio, 100 Degrees), directed by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, who was involved in those discussions. A precursor of Cinema Novo, the film was a symbol not only of Brazilian cinema, but also of the nation’s culture as a whole. Its narrative featuring young black men and the dramas of their everyday lives in the city of Rio de Janeiro wed something to the influence of Italian neorealism. As the title suggests, Rio itself was also one of the leading characters. Rio 40 Graus (Rio, 100 Degrees) is quite unlike the city portrayed in chanchadas or other Brazilian or foreign studio films . Its realist aesthetic, along with the elements it engendered, laid the groundwork for the next trend.

The 1950s-60s, a period of transition with several important events, have been labelled "golden years" for their democratic aura, but this term ignores such major political shocks as President Getúlio Vargas' suicide and a number of attempted military coups. Bossa Nova emerged and a number of social changes were underway while there was talk of prosperity and progress. One slogan of the period referred to compressing 50 years of growth into just 5 years – “50 anos em 5” – and the nation’s capital was transferred from Rio de Janeiro to Brasilia.

In this context of far-reaching transformations, Cinema Novo arose as a high-powered and complex aesthetic movement that some theorists have rated the most significant development in Brazil's cinema history. Its influences came from neorealism, as mentioned above, but also nouvelle vague, cinema-vérité, and Nelson Pereira's films, while dialoguing with Brazilian modernist literature of the 1930s and 40s, and later with Tropicalismo. The movement's leading filmmakers included Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, Glauber Rocha, Cacá Diegues, Ruy Guerra, Leon Hirzman, Paulo César Saraceni, and Walter Hugo Khouri, and their approach to making films in Brazil was based on a new and different vision of the country. Not persuaded that the Brazilian cinema's "industrial" period methods predominant in hegemonic countries should be the standard way of making films, this group sought to compose a different image of the country while making the most of precarious or makeshift technique to forge new aesthetics. Glauber Rocha, who was hailed as the movement's leader due to the active stance seen in his films, writings and political approach, defined the group and its cinema in his well-known "manifesto" Eztetyka da fome (Aesthetics of Hunger):

“From Aruanda to Vidas Secas (Barren Lives), cinema novo has narrated, described, poeticized, discussed, analysed, and agitated the themes of hunger (...); this gallery of starving people that identified cinema novo with the so-called obsession with poverty (miserabilismo) scathed by government and critics in the service of anti-national interests, by producers, and by members of the public – who cannot bear images of their own abject poverty. What made cinema novo an important international phenomenon was precisely its high level of commitment to reality. It was its focus on poverty (miserabilismo), previously found in 1930s literature, now being filmed for 1960s cinema. Poverty had previously been denounced as a social question; now it was to be discussed as a political problem. ”

When the 1964 coup ushered in a new period of dictatorship with repressive legislation (AI-5) , this group's cinema dissipated but one of its strands re-emerged as cinema marginal [outcast cinema]. The new group’s radicalization was expressed more aesthetically with grotesque elements and social outcasts such as prostitutes, delinquents, and aspects of kitsch horror in José Mojica Marins' Zé do Caixão (Coffin Joe). Opposing the ‘aesthetics of hunger’, this group explored ‘trash aesthetics’ with influences from Tropicalismo and mass-media artifices used in transformations then underway in television and the culture industry.

Despite the difficulties of that period, censorship and repression were unable to prevent Brazilian directors producing valuable works for the cinema: O Bandido da Luz Vermelha (The Red Light Bandit) (Rogério Sganzerla, 1968), Matou a família e foi ao cinema (Killed the Family and Went to the Movies) (Júlio Bressane, 1969), Macunaíma (Macunaíma) (Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, 1969), Brasil Ano 2000 (Brazil Year 2000) (Walter Lima Jr., 1969), Os Deuses e os Mortos (Of Gods and the Undead) (Ruy Guerra, 1971), Como era gostoso o meu francês (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman) (Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1971); São Bernardo (Leon Hirszman, 1972), Toda nudez será castigada (All Nudity Shall Be Punished) (Arnaldo Jabor, 1972), Câncer (Cancer) (Glauber Rocha, 1968/72), Xica da Silva (Xica) and Bye Bye Brasil (Bye Bye Brazil) (Cacá Diegues, 1976 and 1979, respectively), A Dama do Lotação (Lady on the Bus) (Neville de Almeida, 1978), which was one of Brazilian cinema's biggest box-office hits, and many others.

The abundance of films produced was not accidental. Although a very hostile period in Brazil, the 1960s and 70s were very relevant in institutional terms for Brazilian cinema. From 1966 to 1975, the National Cinema Institute (INC) attached to the Ministry of Education took steps to support local cinema. A quota system sought to ensure exhibition for Brazilian films; box-office numbers were controlled; awards were geared to revenue and quality; and remittances of takings from foreign films screened in Brazil were taxed for the proceeds to be invested in local cinema. However, the same initiatives revisited many years later by ANCINE were unable to obtain much space in the market for Cinema Novo films. An exception was Joaquim Pedro's 1968 box-office hit Macunaíma (Macunaíma), which was taken as benchmark for mainstream cinema in Brazil at the time.

The situation took on new proportions when EMBRAFILME was introduced in 1969, as the State recognized that culture and communication involved power relations. New institutions were designed to manage culture in line with the development of capitalism in Brazil: the Ministry of Telecommunications (1967), Telebrás (1972), Funarte (1975) and Radiobrás (1976) . A point to note is that Brazil did not have a Ministry of Culture until 1985.

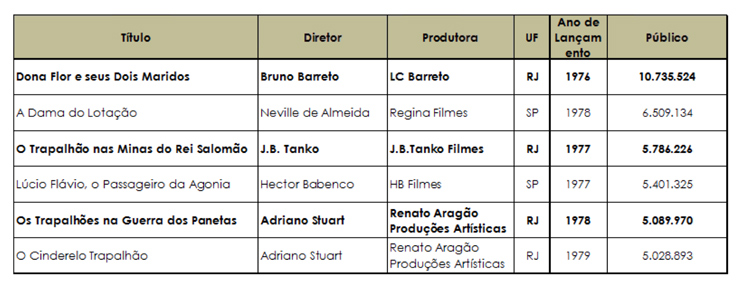

In the 1957-1966 period, an average of 32 films a year were made in Brazil. From 1966 to 1969, the annual number rose to 50 and then to over 80 in the 1970s and 80s. Embrafilme intervened in production and distribution and audiences watching Brazilian films reached 30%, their highest level to date. Exhibition was also affected by policy requiring locally made films and regulating box-office reports to ensure systematic statistical data. In the same period, the number of theatres in Brazil reached its highest level ever at 3,276 in 1975 and Brazilian film was buoyed by this growth with features on programs all over the country. In the late 1970s, the era of the 'economic miracle', many local films drew large audiences, including:

In the early 1980s, a few films had their box-office numbers counted in the millions and Brazilian films retained a large market share. However, high revenues from the early 1980s failed to inoculate the industry against the severe economic crisis that gripped the country in the wake of the so-called 'economic miracle'. Rampant inflation, high unemployment and a shrinking economy earned the 1980s their "lost decade" epithet. On the political side, the dictatorial regime agreed to start a transition to civilian government in 1985. Subsequent direct elections in 1989 saw the rise of President Fernando Collor and his ideology of cutting back the role of the state. His administration's dismantling of the state apparatus axed EMBRAFILME, Concine (National Film Council), the Brazilian Cinema Foundation and the Ministry of Culture. Regulatory frameworks and industry databases were dropped too, so by the early 1990s feature-film production in Brazil had been all but annihilated. The period was one of remarkable hardship for filmmakers in Brazil.

In the wake of mobilizations organized by artists and filmmakers, new legislation enacted in 1991 and 1993 sought to address this scenario: the Rouanet Law and the Audiovisual Law. By the mid-90s, local film production was beginning to revive and there was talk of Brazilian cinema's "resurgence" – a word that led to controversy since there was no new movement emerging. The iconic film of the time was Carlota Joaquina, princesa do Brasil (Carlota Joaquina, Princess of Brazil), made by director and actor Carla Camurati, who set up an independent distribution system that drew over 1.2 million viewers.

This new funding model prompted the Brazilian State to invest in cinema again to drive its growth, but this time working indirectly through private-sector partnerships. Although controversial and criticized to this day, this new form of funding did succeed in raising production to higher levels by 1999.

Stabilizing the economy's price levels was the highlight of 1994 and the new currency led to positive expectation of change. Cinema cashed in on this trend with exhibitors’ takings picking up as they opened multiplex cinemas in shopping malls and targeted up-market audiences in theatres gentrified by higher ticket prices.

By the second half of the 1990s, some Brazilian films were winning acclaim internationally. In 1997, director Bruno Barreto's O que é isso companheiro? (Four Days in September) was nominated for a 'Best Foreign Film' Oscar. In 1998, Walter Salles' Central do Brasil (Central Station) took the Berlin Film Festival's top award, the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film, besides two nominations to the Oscar Awards that included that of Fernanda Montenegro, for Best Actress. In addition to international recognition, films for children and teens were successful. Stars such as Xuxa and Renato Aragão had been signed by TV Globo, the country's biggest television network, and from 1997 to 2001 both made several films that drew a combined total audience of over 10 million, thus economically sustaining part of the domestic cinema industry. Their success displayed the formula of using Brazilian television talents for cinema too, which Globo Filmes (TV Globo's film division) drew on from 1997 onwards.

Although the market had substantially improved by the late 1990s, its representatives pushed for a more comprehensive policy that would build a solid industrial base for Brazilian cinema. The film industry and government held conferences and set up working groups in the early 2000s to draft legislation and found the Agência Nacional de Cinema (National Cinema Agency) – ANCINE in 2001, thus flagging a new phase for the State’s involvement in Brazilian cinema.

Given the new agency and sources of support, the 2000s were starting with much more promising prospects than the 1990s. Having ANCINE as an agency focused on cinematographic activity was a big step forward that recognized the sector as strategic for the country and pointed to a more robust framework for government initiatives in this sector. Provisional Measure 2228 of 2001 enabled ANCINE to foster the sector's activities and provide regulatory framework and oversight. As a separate entity attached to the Ministry of Culture, ANCINE determines audiovisual policy together with the Conselho Nacional de Cinema (National Film Board) and the Ministry's Audiovisual Department. ANCINE also runs Brazil's cinema archives (Cinemateca Brasileira) in São Paulo and the Audiovisual Technical Centre in Rio de Janeiro as part of federal audiovisual preservation policy. In the course of the 2000s, the agency arranged new sources of funding as a robust basis for this sector, and the consequences were soon felt.

Many outstanding films were made in this new period, but the highlight both nationally and internationally was undoubtedly Cidade de Deus (City of God) directed by Fernando Meirelles and co-directed by Katia Lund (2002). Shown hors de concours at Cannes, the film won great acclaim that transformed its career in Brazil and internationally with unprecedented accolades for Brazilian cinema – four Oscar nominations for best director, adapted screenplay, editing and cinematography. Although the film was the butt of harsh criticism in Brazil at the time of its release campaign, its audience numbers of over 3 million made it one of the biggest ever Brazilian films internationally and an important reference for world cinema too. Several standout Brazilian films followed in the aftermath of its success.

From the 1990s "resurgence" through 2003, some 20 to 30 full-length feature films were released to theatres every year. From 2009 onwards, the annual total rose significantly to over 80.

By the end of the decade, Brazilian films were winning major international awards. Ten years after Central do Brasil (Central Station), another Brazilian film took the top award: José Padilha's Elite Squad, which was released in Brazil in late 2007 to hostile reviews due to its portrayal of controversial issues such as drug use and violent policing. Nevertheless, the film headlined in Brazil when pirated copies leaked from official sources led to huge box-office numbers (over three million) while informal-market sales of pirate DVDs showed its popularity. Some characters' lines became household catch phrases.

Continue reading Mapping Brazil - Cinema: Artistic Diversity Behind the Figures I