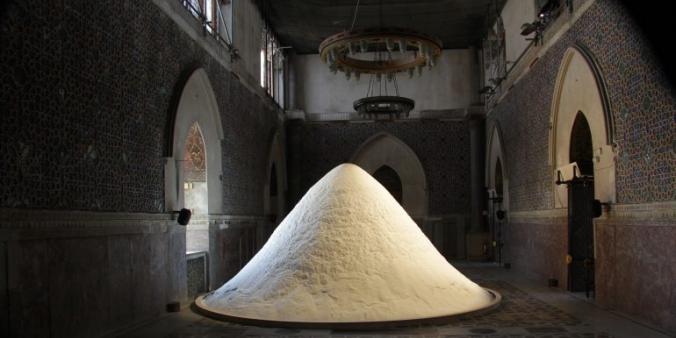

We spoke to Staal at the nomadic Transeuropa Festival, organised by European Alternatives in the city of Palermo. Jonas Staal’s artwork New Unions was set up as an artistic and political campaign launched in 2016. In a site-specific exhibition developed for the festival, the artist transformed Palermo's Teatro Garibaldi offering a retrospective of the work done by the campaign while simultaneously constructing a space to host debates and meetings.

From a large-scale floor carpet that maps progressive parties and platforms across the European continent to video works visualising alternative parliaments in abandoned stadiums and oil rigs, from national flags, turned into Pan-European symbols to large constructivist stars emerging from the floor; Staal’s projects turned the theatre into the festival’s focal point. In addition, MIT Press recently published his book Propaganda Art in the 21st century, an expansion of his PhD dissertation at the University of Leiden. The artist elaborated - over pizza in Palermo - on his campaign for the political imagination.

What is 'New Unions' about and what is the significance of the city of Palermo, the Transeuropa festival and this particular theatre as the sites for this artwork?

"The New Unions map was made specifically for the Teatro Garibaldi, and it is the fourth in a series of alternative maps of Europe. By mapping out various internationalist and transnational political parties, it imagines future political compositions. The 'Union' part is the more interesting component when we talk about the EU because it requires us to think about what it means to unionize transnationally from a social, ecologist and feminist point of view.

For me, the setting of Palermo is almost instinctive, because emancipatory forms of culture always thrive in emancipatory political landscapes, and Palermo certainly stands out within that category in its defence of the rights of migrants and refugees. The festival enjoys support from a progressive municipality here that takes the discussion around the arts and culture very seriously. During the opening press conference, we discussed the meaning of art in the municipal council, and, moments later, we discussed politics in an artistic context at the festival’s ‘headquarters’ that I created right here. At the best of moments, the imaginary of art and politics can further one another. They might not be the same, but shape one another in the process of bringing into being new egalitarian worlds.

This dynamic can be seen all over the Transeuropa Festival and the coinciding BAM Biennale where the political engagement of artists is explicit. Other than that, a large part of the programming takes place in public spaces – and not only within the historical centro, but throughout the entire city. It reflects a strong recognition of the public ownership of culture, by which its collective value is emphasized."

In your book, you discuss the need to develop propagandistic art to replace so-called ‘master narratives’, such as the neoliberal or ultranationalist ones. What does your installation 'New Unions' do to counter them?

"Let me give an example: the municipalist movements – in which Palermo plays a key role – are a great model to follow but at the same time, the systemic scale of the global crisis cannot be faced by cities alone. A city like Barcelona cannot tackle the climate crisis by itself. The New Unions project aims to demonstrate that all these political efforts are not isolated attempts, as it projects new imagined unions through the map. My aim is to contribute, through art, to alternative visions of transnational unions that go beyond the Leave/Remain dichotomy; beyond ultranationalism and neoliberal austerity.

An artistic campaign like the one I made goes beyond such dichotomies. They represent two forms of politics that should be rejected simultaneously. The artistic task, in this case, is to navigate between reality and potentiality to enable alternatives. Concretely, the campaign proposes different kinds of interventions, such as the transnational parliaments set up in decommissioned oil rigs or in stadiums that were abandoned in the Greek economic crisis. We use these speculative models of future politics to enable new political possibilities in the present.

Wherever there is power, there is propaganda. Whether it takes an oppressive or emancipatory form, depends on the kind of power in question. In my book, I examine the role of propaganda in socialist, anti-colonial, feminist and radical ecological movements, which does not manifest as a manipulative force, but as a liberatory one: collective propagandas that agitate and mobilize new imaginaries of egalitarian worlds to come. Yet, the connotation with totalitarianism is so strong that the term propaganda tends to be discarded quite quickly."

Are there any elements that you incorporated into your work after studying the propaganda of totalitarian regimes? Is there anything that the propaganda artist can learn from, say, Mussolini or Goebbels?

"Dictatorships such as Italian fascism employed techniques of extrapolation and grotesque imagery, and they were very effective. But these strategies and forms result directly from their authoritarian and anti-democratic convictions, with an expressed desire to impose violence upon minorities and political opponents – which stands radically opposed to the agenda of emancipatory politics. What we can learn is to recognize particular desires for order and control, often structured on a false construction of an enemy, and fight and resist them at every step.

Different than the authoritarian fascist imagination, an emancipatory politics should be collective and transparent; you’re building processes in which you create new stories. Not the false mythology of a return to a sovereign and “pure” People that never existed in the first place, but a future yet to be won as a people-in-the-making: a conception of a people in a constant process of articulation. You cannot take an authoritarian fascist strategy and fill it up with nice progressive ideas. The forms of authoritarian fascist propaganda are the direct result of its convictions and aims. Emancipatory politics enables fundamentally different stories, other narratives, other visual forms and other forms of life."

In these very fluid times, and as an artist operating almost only internationally, what does being Dutch mean for you as an artist? Is it an empty shell for you?

"In my view, transnationalism does not imply the negation of cultural specificity. The transnationalism that is celebrated here at the Transeuropa festival, is of a very different kind than the one exhibited by corporate bankers and the empty mailboxes of the Zuidas (banking district of Amsterdam, ed.). What we would propagandistically call the 'globalist order of transnationalism', results in a very generic type of culture, as exemplified in modern cities. The city centres of the world increasingly occupied by upper classes, tourists and chain stores. It makes them interchangeable and pushes people out of their situatedness: who can still live in the city centres of Amsterdam, London or Paris?

The idea of transnationalism that I share with Transeuropa affirms the importance of this situatedness, of cultures that emerge from a place-based understanding in the world. We do, however, emphasise shared collective interests as well. The protection of workers’ rights, access to education, health care and a safe ecosystem: they all have a different impact on different local contexts, but they are shared problems. And that is what a transnational union should be based on."

This requires a bigger union than anything we know so far.

"Absolutely. This is a time when planetary politics are more needed than ever. But everyone has a placed-based understanding of the world, at least most people still have. It is shaped by culture through language, ritual and symbolism, but also through the lived experience of having emerged from a colonizer culture, or one that has faced colonization – these particularities and differences cannot and should not be denied. They define our place and role in a bigger political project, and articulate the kinds of justice we need to seek together."

So what role do nation-states have in that sense? What message should they propagate, and what role can national cultural institutes play in this?

"The national funding structures of art mirror global inequalities. Affluent countries propagate their artist disproportionately across the world, compared to countries with less financial means. The Mondriaan Fund plays a prominent role in subsidising the presence of Dutch artists abroad, which is fantastic for those registered in the Netherlands, but risks overrepresentation. It would be important to match funding to national artists when working abroad to the long-term strengthening of the local institutions that host them, so that cultural funds become part of a project of fundamental redistribution.

I have to think about what you write about neutrality in your book: what is the danger of having a neutral outlook on cultural activities?

"By definition, I don’t believe in artistic neutrality, as there is always a relation between art and power. A former colonial power such as the Netherlands still benefits in terms of its capital and position in geopolitics from this brutal heritage. The belief in neutrality is a very useful propaganda tool for liberal democracies because it preserves the status quo, while not having to address historical injustices and the way they continue to shape our present and future.

We need a real discussion on the principles based on which we propagate our cultural apparatus, To give you an example: many of my Turkish and Kurdish friends – artists, activists and academics – are persecuted because they protested the Erdoğan regime’s war against the Kurds and other abuse of state power. Our support should be first and foremost with these progressive opposition forces in Turkey, and we must speak out and act against the regime every step of the way. Now, the fake-neutralism prioritized in “keeping good relationships” effectively provides cultural legitimacy to dictatorships that structurally incarcerate, torture and murder."

Duly noted... Among artists, the climate is an increasingly salient issue. What is the changing role of the artist with regard to the climate, both practically and in terms of the climate as a subject? What kind of art is needed in climate catastrophe?

"I am very opposed to the individualisation of the climate crisis. This doesn’t mean that we should disregard our individual choices on how to act ethically in our communities; it is important to be existentially rooted in a place in the world and that you do the right thing in your own direct environment. But those individual choices – however important they might seem – have no actual bearing on the climate catastrophe, which for two-thirds can be accounted for by the fossil fuel industry. They need to be broken up and their CEOs should be immediately persecuted. They belong in jail for committing intergenerational climate crimes, not at Davos.

In this process towards climate justice, it is important to acknowledge that across the world our present is not equal. In the Western context, you often hear people exclaim: “we only have ten more years to act!” But there are many communities, for example in Brazil and the Philippines, where the devastating effects of climate catastrophe are already fully experienced: they never had “ten years to act” in the first place. In these contexts, climate activists work at the highest possible risk.

Enforcing intergenerational climate justice demands a fundamental change; to recognize climate crimes of the past, present and future. Climate criminals employ a form of cognitive dissonance, in that the consequences of their crimes in the present will only fully manifest in the future. We need to make them accountable to the full extent for their war on the future.

For artists, this requires to push for the transformation of our institutions. We seem to presume that there will be an art history of the future, but nothing in the present points to that: it’s the very possibility of the future that is being undone. To reclaim the possibility of a future, we are in need of a new master narrative in which politics, justice and culture are practised intergenerationally. I think art plays a key role in the process of popularizing such a narrative."

What are some positive examples of artists who are paving the way in this regard?

"Forensic Architecture’s project on Herbicidal Warfare in Gaza is a good example. They're a collective from London who shows how climate is being weaponized in certain areas around the world. Climate change is embedded in global geopolitics in a different way than most people assume. The fact that regimes accelerate processes of desertification against their enemies makes clear that we are in the midst not just of a climate crisis, but a perpetual climate war.

On the topic of intergenerationality, Patricia Kaersenhout brings into being new canons of underrepresented or actively repressed narratives of knowledge and resistance. In Guess who’s coming to dinner too, - that responds to Judy Chicago’s famous Dinner Party (1979) – she organizes an intergenerational assembly of black women and women of colour from various eras, from spiritual guides to liberational icons, from artists to activists. Here, pasts and presents congregate, in the process of evoking an egalitarian future.

Generally, sometimes you only need a micropolitical practice of possibility to bring about change. Look at when people in Iceland were rewriting the constitution after the crisis; many continue to reference this moment as an example of transformative democracy. A small case – even without having had any planetary application – can inspire real action in the now: it was possible there, then why not here? Building a new intergenerational and transnational consciousness in this way, joining dots throughout time and space, mobilizes the imagination of alternate futures, enabling real action in the present."

Thank you, Jonas, I do think you’re playing an important role in this regard as well, by showing Unions where people might not expect them. I hope you continue to do so.

"Thanks for the compliment; and no, I’m not entertaining any retirement plans just yet."