In our new article series NewGen - Above and Beyond, DutchCulture asked young writers from around the world to catch impressions of the ripples created by young creatives, makers, artists and cultural professionals in their cities. In this series of articles, we will travel to Warsaw, Casablanca, Paramaribo, Lyon, Shanghai and Bristol to see the world through the perspective of a new generation of artists and cultural professionals. What is specific about the way they shape and create their work? What themes are they putting forward and what's their take on working across borders?

Episode #1: Casablanca

Chama Tahiri Ivorra is a creative director, producer, and journalist based in Casablanca and Paris. She wrote this article for this series, as well as ahead of the opening of the exhibition The Other Story, curated by Abdelkader Benali in the CoBrA Museum in Amstelveen. Many of the artists mentioned in this article are exhibited in this important ensemble of Moroccan modernism. The exhibition will open on April 14 with a live event at the museum, moderated by our Morocco advisor Myriam Sahraoui.

The Casablanca School: a first counterculture movement

The artists of the Casablanca School, a modernist art movement in the 1960s led by painters Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Melehi, and Mohamed Chabâa, are now among many on display at the Cobra Museum. They were among the first Moroccan artists to express a cultural claim on their native city from a post-colonial narrative. Sixty years later, does their heritage carry on? Knowing that political colonialism shifted to a more intellectual and cultural hegemony of the West, what story of the city is the young generation telling?

Crushing or inspiring

“We can’t separate Casa from her colonial past. But the way the city evolved is another story,” explains artist and architect Aïcha El Beloui, dedicated in her practice to highlighting forgotten and unwritten historical narratives about her city. The intense rural exodus and constant growth of its population have made Casablanca a laboratory for modern architecture - yet it was also where the French word for slum, bidonville, was invented. “Casa’s identity today is the result of very violent frictions where everyone’s trying to make it. Then it’s up to you what you do with this energy. It’s either crushing or inspiring,” pursues El Beloui. The real identity of the city, made by and for locals, therefore begins to be shaped in the late fifties after the end of the period of French military occupation of Morocco - an extension of the colonial regime that lasted until 1956.

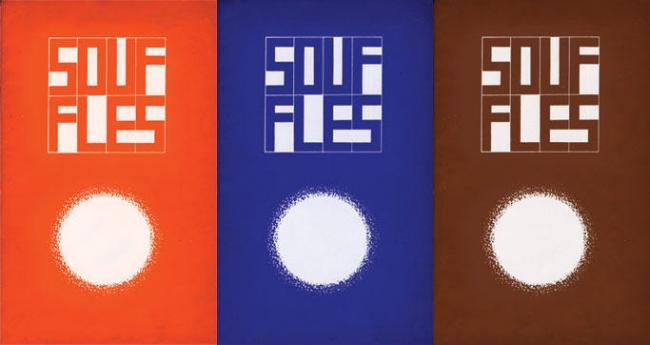

The School of Fine Arts of Casablanca, founded in 1919, traditionally required that all instructors were French. Moroccan students weren't allowed to exhibit their works and were pushed to pursue craftsmanship and design. They could not develop further than to become technicians to assist the French, who were encouraged and nurtured in the fine arts. “The story of Moroccan art has been a European speciality for over half a century, a monopoly of the western science,” as poet Abdellatif Laâbi wrote in Souffles magazine in the late 1960s. Souffles became a key intellectual and countercultural space of experimentation and political statements that held the hopes of a cultural revolution in Morocco.

The end of a social and artistic utopia

In this vein, a radical change had also come at the School of Fine Arts, where Farid Belkahia took over in 1962. He broke free from Western perspectives and fashion, drawing inspiration from local crafts and traditional practices, integrating calligraphy or Amazigh heritage for instance. The Casablanca School expanded to different areas of the creative scene in Morocco, bringing together a large community of artists and activists.

Much of this creative energy came together in the manifest-exhibition Présence Plastique in 1969. Souffles-founders Laâbi and Mohamed Melehi gained international recognition and shone a new light on Morocco and especially Casablanca, mostly known back then for its art deco heritage and the famous movie Casablanca (Michael Curtiz, 1942). In a documentary filmed by Shalom Gorewitz, Mohamed Melehi stated that “North Africa has been a source of inspiration and revelation for many Western artists.”

In 1972, the magazine Souffles - having slowly turned into a platform for the Moroccan Marxist-Leninist movement - was banned, and its founders were jailed and tortured. The rise of such repression marked the end of what seemed to be a social and artistic utopia, having laid the groundwork for Moroccan modern art.

The new 'Casaoui' scene: looking inward

Nowadays, although the art scene is rather scattered and eclectic, artists and creatives mostly share that conflictual love-hate relationship to the city that both inspires and frustrates them. As far as Aïcha El Beloui is concerned: “Living abroad is what allowed me to see Casa differently on the daily basis. To keep a healthy relationship with the city you need to leave regularly and come back.”

A vision also shared by self-taught street photographer and hip-hop dancer Yassine Ismaili Alaoui, aka Yoriyas, whose gaze on Casablanca totally shifted after his first trip away for a competition. “The specificities and vibrant energy of the city I had always known, struck me. This is when I understood that our creative inspiration should come from where we come from,” he says. Berlin-based curator and ifa-Gallery director Alya Sebti goes even further. “There’s a tendency from our cultural institutions to look at the North like it’s the only horizon, when we need to look more inwards and question what we do and where we come from.” She remains admirative of the people who managed to stay but claims she’d rather love from a distance - a quintessential diasporic condition.

Reclaiming the city's heritage

For artists like Mohamed Fariji Hassan Darsi or Zineb Andress Arraki (ZAA), creating a new narrative first comes from reclaiming the city’s heritage, both material and immaterial, and working towards its preservation. In 2002, Darsi’s model of the Hermitage park, later acquired by the Centre Pompidou in Paris, shone a light on the state of abandonment of one of the very few green spaces of the city which led to its restoration in 2010. “A city should be negotiated,” he claims, implying that we often take and destroy unilaterally, ironically falling into the same perverted colonial schemes of appropriation and destruction without permission.

As so many social and cultural landmarks in Casablanca are falling into oblivion, burying with them parts of history, what can artists do? The slaughterhouse of Casablanca was the first brownfield turned into a cultural space in the Arab world in 2008. Citizens and activists, including Aïcha El Beloui, who wrote her college thesis about it, tried to keep it alive through the non-profit Casamémoire, but it ultimately was left to fall into ruins due to a lack of management and institutional support.

For ZAA, coming to terms with a shared past as a society first needs archiving. She resents the fact that the memory of the city is being erased as if nothing ever existed, and as if there's no proper identity. “We’re tearing all our heritage down and building a new globalised architecture from scratch that has nothing to do whatsoever with our culture,” she says. Her series of photographs of abandoned places is a way for her to deal with this frustration: “I want to photograph it all so that we don’t forget.”

Mohamed Fariji Hassan Darsi's Collective Museum of Casablanca also works on preserving the memory of the city, collecting objects and documents bound to disappear and exhibiting them in nomad and ephemeral public spaces. “It is meant to offer a shared process of creating a narrative that allows a negotiation with the city and the construction of a critical mind for its inhabitants,” explains co-founder Léa Morin at a conference in 2018.

This nostalgia and will to preserve the past are also found in more abstract and poetic approaches. Take for example Deborah Benzaquen who photographed the remains of an amusement park that is incidentally the subject of the current Collective Museum’s exhibition. In her latest works though, she shifts her focus to more intimate stories about misfits and marginalised people with the series Super Héros, and later Sweet Surrender, a portrait of a non-binary liberated youth.

From preserving material heritage to celebrating pop culture

Replacing the subject at the centre of the artistic approach is probably an essential process to rehumanise the city and let go of the scientific focus inherited by the French. Morocco’s pioneer pop art artist Hassan Hajjaj was the first to play with the popular culture codes, including counterfeit goods, and to reverse the western gaze placing the people at the centre of his compositions, disrupting the codes of fashion and magazines that used cities like Marrakech solely as an exotic background. Boosted by the culture of Instagram and self-staging, fashion has been a natural way of expression for Casaouis (inhabitants of Casablanca) for decades. Joseph Ouechen started fashion street photography in the early 2010s and managed to propel himself from the slum of Sidi Moumen to Elle Magazine.

Casablanca counts many similar success stories as social media empowered young creatives to get a voice and tell their own stories, offering a new, fresh and edgy perspective on a still over-folklorised country and culture. From Hay Mohammadi, Karim Chater, through his @style_beldi feed - literally: popular, traditional style - is defining the very essence of Moroccanness and what makes someone a true Casaoui. His quirky outfits and deceiving confidence got him features on GQ and Hype Beast Arabia.

Little magic moments

While most movies have been depicting a rather miserabilist portrait of the city for the past 20 years, these artists tend to look for the little magic moments in the cracks of the unmerciful concrete. While the roughness of Casablanca is real, they manage - sometimes with a dash of humour - to gracefully highlight what brings people together and makes the city so endearing with effortless ease. Their profound attachment to Casa led them to maybe unintentionally shape a post-colonial narrative to reclaim their city. Yoriyas's first series that made him famous was titled Casablanca, not the movie in an attempt to document Casa as it is here and now, for future generations to be able to look back and know what it was like to live in the biggest city of the country in the 21st century.

Although his compositions are always very thought through and might have to do with some sort of magic of the moment, his goal isn’t to show Casa as pretty or ugly, but as it is. Coming from the suburbs as well, he belongs to that generation who stand for their neighbourhoods and defy classism and determinism that are directly connected to how the city was built as it mushroomed during the French protectorate. As claims Mohammed Amine Bellaoui, aka Rebel Spirit, School of Fine Arts alumni and celebrity street artist (amongst other talents): “It’s the energy of the ‘scary’ suburbs, beyond the highway, that holds the very spirit of Casablanca.” He also makes a reference to the movie in the design of his graphic novel Le Guide Casablancais, where he details the specificity of the Casaoui way of life, through the daily struggles of a mundane antihero.

The claim on public space

In other respects, street art is nowadays very far from its subversive origins, commissioned and instrumentalised by institutions incapable of providing actual content. Whole buildings of social housing are now covered with gigantic vibrant frescos, as a way to draw the attention away from the lack of actual cultural offers, and social solutions. PhD in sociology, Cléo Marmié, explains: “Integrated into Casablanca’s urban strategy and marketing, street art also participates in the country’s soft power. It shows a modern and open image of the country and at the same time, the pieces lose their virulence and anti-establishment edge. As street art makes its way into art galleries, the political statements of the works get even more diluted to meet the commercial needs of the contemporary art market.” As such, it has become a way to control an artistic expression that once was regarded as underground and dissident.

Therefore, one of the major stakes that artists share is the mediation with the public and the possibility to occupy and claim public space, which is not a given in a country where freedom, not only of speech, is not always guaranteed. The times when Melehi had an open studio in a very popular neighbourhood in order to keep a constant dialogue with the viewers are over, but the need for genuine connections and open dialogues is pressing more than ever. For instance, in the exhibition Ce qui s’oublie et ce qui reste, curated by Meriem Berrada from the MACAAL at the Museum of Migration in Paris during the Cultural Season African 2020, the viewer is repeatedly made aware of their responsibility towards the narratives that are being presented to them, mobilising them into the duty of memory and conservation of the works. A heavy burden to carry for a population in Casablanca that is still too often in survival mode and has no tools and no art education due to a lack of plans from the government, despite some institutions’ efforts.

Sixty years after the Casablanca School, a research residency led by independent curator Fatim Zahra Lakhrissa and supported by local and foreign private institutions aims to reflect upon the heritage of the movement through a contemporary prism. It combines on the one hand archiving, valuing, and reviving the immense body of works of the Casablanca School era, and on the other hand creating and exhibiting new material as a natural extension of what was once the dream of a generation. Maybe a final cathartic act of reconciliation?