DutchCulture asked 6 journalists from around the world to catch impressions of the ripples created by young creatives, makers, artists, or cultural professionals in their cities. In this series of articles, we travel to Warsaw, Casablanca, Paramaribo, Lyon, Shanghai and Bristol to see the world from the perspective of a new generation of artists and cultural professionals. What’s specific about the way they shape and create their work? What themes are they putting forward and what's their take on working across borders?

Episode #2: Warsaw

Karolina Plinta is an art critic, deputy editor-in-chief of the magazine Szum, member of The International Association of Art Critics AICA. She lives in Warsaw and Szczecin, Poland. As she notices, thanks to young artists from Ukraine and Belarus, the Polish art scene is becoming more and more sensitive to the perspective of foreigners and Polish migration policy.

Opposition

The art scene in Poland has undergone a significant evolution in recent years thanks to young artists, who to be more politically involved than their predecessors, and its sensitivity seems to be a response to the hostile political context in which it has developed. Since the right-wing party Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) took power in Poland in 2015, nationalist and xenophobic tendencies have been growing in the country. Young artists feel that they have to oppose them, which is reflected in numerous actions, initiated, for example, by groups such as the Consortium of Post-Artistic Practices.

Another important element that deconstructs conservative discourses and influences the shape of the Polish art scene is the increasing migration of artists to Poland from other countries – in recent years mainly from Belarus and Ukraine. Their presence significantly sensitised the local art scene to the situation of neighbouring countries, influenced our attitude towards migrants, and revealed the colonial clichés that rule the Polish imagination.

Importantly, this is rather a new phenomenon. Until recently, the Polish artistic community was quite closed and self-centered. Only city galleries operating in the eastern part of the country, such as Galeria Arsenał in Białystok or Galeria Labirynt in Lublin, tried to work with artists from across the eastern border to a greater extent. The situation changed with the increasing economic migration of people from Ukraine and Belarus to the center of Poland, which started in 2014. This phenomenon slowly began to be noticed in the art scene. For example, the 10th edition of the Warsaw Under Construction festival (2018), organised by the Museum of Modern Art, was held under the slogan Neighbors, and its co-organisers were curators from the Center for Research on Visual Culture in Kyiv. In 2019, the exhibition Foreign artists living in Poland was held as part of the Biennale Warszawa, curated by Janek Simon. It was an important gesture that became an impulse for further actions.

Foreign artist

In 2020, members of ZA*Group (Ukrainian artists Yuriy Biley and Yulia Krivich, and Belarusian curator Vera Zalutskaya) created ZA*ZIN – a zine dedicated to foreign artists living in Poland (ZA stands for Zagraniczni Artyst*, meaning Foreign Artists). The aim of this publication was to problematise the experience of migration and the life of migrants in Poland. ZA*ZIN also acts as a guide for migrants and is a place where foreign artists can share their experiences. Through their activities, the founders of ZA*ZIN also want to combat prejudices against migrants in Poland. Migrants from Ukraine or Belarus are most often perceived as cheap labour. However, they are often highly qualified people such as doctors, nurses, technical specialists and finally artists, educated in good academies in their home countries. They often come to Poland permanently and co-create Polish society, in spite of nationalist narratives. “This country is changing, people of different nationalities come, they are new Poles. In our project, we are talking about Poland, which is changing on many levels," says Yuryi Biley, describing the ZA*ZIN mission.

Linguistic stigma

The importance of changing the attitude of Poles towards migrants was demonstrated by the action W Ukrainie (In Ukraine) by Ukrainian photographer and artist Yulia Krivich in 2019. As part of the action, Krivich went to the West Railway Station in Warsaw (the end station of many Ukrainians traveling to Warsaw) with a flag with the words "In Ukraine". There she took a symbolic photo of herself, later published on the Internet. She repeated her actions in Wrocław, where she handed out stickers with the words "In Ukraine". By this action, Krivich wants to draw attention to pronouns that are used in Polish in relation to Ukraine. When describing events in Ukraine, Poles usually use the pronoun na (i.e. na Ukrainie, meaning on Ukraine), which is a reminiscence of the times when the territory of Ukraine was part of the Kingdom of Poland. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, some linguists have started to use the preposition ’w’ in relation to Ukraine to emphasise its independence, but this is not a common practice. Krivich's actions, disseminated by the media, gave rise to a public debate that still arouses emotions today.

Accurate translation of the work: Knowledge of immigrant women the wealth of the motherland.

“I got hate for the fact that, as an immigrant from Ukraine, I dare to change the Polish language. The holy Polish language is like John Paul II,” comments Krivich.

Despite these controversies, the phrase In Ukraine is becoming more and more common in Polish media and in everyday use. Krivich's appeal to emphasise the independence of Ukraine in linguistic form is particularly relevant in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began last February.

It is also worth noting that not only Krivich tried to work through problematic phrases and terms in Polish. In 2017, Belarus artist Jana Shostak launched the media campaign nowacy by introducing the word nowak (a homonym of one of the most popular surnames in Poland, derived from the words new or newcomer) to the public space as an alternative word for refugee. Shostak popularised the term on television, the internet and radio, gaining a lot of media exposure. In order to promote the idea of nowaks, she also took part in local beauty contests – she even won the title of vice miss of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. She documented this in the film Miss Polonia, produced together with Jakub Jasiukiewicz. The term nowaks has not caught on in everyday Polish so far, but the Shostak campaign drew attention to the problem of linguistic stigma.

Fuck the system

Thanks to her determination, Shostak also managed to become the voice of the Belarusian community in Poland. In 2020, she actively involved in anti-government protests in Belarus. In Poland, she initiated the action A minute of screaming for Belarus. In May 2021, after Roman Pietrasewicz was arrested by the Belarusian authorities, during a press conference at the Belarusian embassy in Warsaw Shostak appeared in a white and red dress and started screaming terrifyingly. Her protest received wide media coverage, not only because of the scream itself, but also because she was not wearing a bra!

The artist decided to take advantage of this moral controversy: in order to draw attention to companies related to the Lukashenko regime, she wrote their names and logos on her own chest, like a tattoo. Other people, mostly women, joined her protest.

Shostak also tries to defend the rights of Belarusians living in Poland. For example, at the beginning of the pandemic, Poland stopped issuing tourist visas for Belarusians. Even after the sanitary regime was relaxed, this did not change. On September 8, during the meeting of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki with the leader of the Belarusian opposition Swiatłana Cichanouska, Jana Shostak decided to shout at the Prime Minister to draw his attention to the problem of visas. Thanks to her protest, Poland has been re-issuing tourist visas to Belarusians since September 17, 2021. Shostak's actions may evoke associations with the actions of Russian actionists such as Petr Pavlensky or Pussy Riot, but distinguishes herself by trying to act legally. "It's not hard to fuck the system, the trick is to maneuver it legally, seemingly being polite and obedient," she says.

As the artist explains, it is important for her to hack the patriarchal system from the inside. She describes his strategy as ’WTF activism’, by which she means using unconventional tools to draw attention to problems. This kind of activism is followed by other artists. Take for example the charity calendar #dekoltdlabialorusi (Neckline for Belarus) by the Laski collective. Female Polish artists and celebrities posed for the calendar without bras with cute kittens on their shoulders. Why? Because nothing draws more attention than boobs and cats. Sales profits = are donated to the families of Belarusian political prisoners.

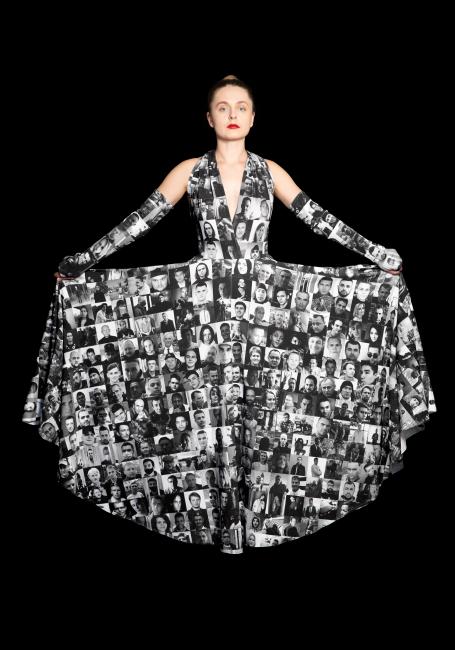

Shostak is recognised in Poland for her activism. In January 2022, the Polityka magazine awarded her with the prestigious Polityka Passports award in the visual arts category (ex aequo with artist Mikołaj Sobczak). The artist appeared at the awards gala wearing a dress with images of 1,200 prisoners of the Lukashenko regime. But it also has a dark side: in her own country, Shostak is on terrorist lists. In numerous interviews, she admits that activism is very exploitative and she often feels exhausted. Despite this, she does not quit. Currently, she is one of the members of the informal and underground activist group Partyzantka, consisting of Belarusian women (recently also Polish women) operating in Warsaw. At this point, they help nowaks fleeing the war in Ukraine.

Supporting immigrants and refugees

Despite the increasing number of people migrating to Poland, the country does not have a substantial migration policy. The widespread prejudice against migrants, especially those of dark skin color and originating from Arab countries, is also a big problem. This was painfully demonstrated by the humanitarian crisis on the border between Belarus and the European Union, which has been going on since the summer of 2021. For this reason, more and more Polish artists are becoming sensitive to the needs and situation of migrants in Poland. Polish artist and activist Pamela Bożek is a good example. Since 2018, Pamela Bożek has been cooperating with people staying at the Centre for Foreigners in Łuków (a city close to Warsaw), organising workshops and aid campaigns. She is the founder of the project-collective Notebooks from Łuków, which is working together with the residents of the Centre in Łuków: Zaira Avtaeva, Zalina Tavgereeva, Liana Borczaszvilli, Makka Visengereeva, Khava Bashanova, and Ajna Malcagova. They produce blank notebooks - stationery items for sale, and the profits support migrants who are waiting with their families to be granted international protection. Bożek is also the publisher and editor of the zine Wiza-Vis, co-created by refugees in Poland. Together with artists Ala Savashevich and Iwona Ogrodzka, she forms the Bezgraniczna Pomoc group, which organises art auctions, aimed at supporting people with migrant and refugee backgrounds in Poland.

It seems that not only artists, but also institutions are beginning to realise the importance of the problems of increasing migration and the value of alliances based on empathy and transnational solidarity. In 2020, as part of the 12th edition of the Warsaw Under Construction festival, artist Taras Gembik and educator Maria Beburia founded the Blyzkist group (blyzkist can be translated as proximity). Blyzkist operates at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw and is an initiative that aims to research the needs of the Ukrainian and Belarusian communities in Warsaw. After Russia's attack on Ukraine, when many refugees began arriving in the Polish capital, Blyzkist took the form of an aid initiative: people involved in the group's activities collect medicines, distribute sandwiches, hot meals, and hygiene products to aid centres, night shelters and information points in Warsaw train stations. Blyzkist is about to evolve into a community centre for people needing help.

A few days after the outbreak of the war, I spoke with a young Ukrainian curator, Asia Tsisiar, working in Poland at the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation. She was touched by the help Poles are offering to Ukrainians at this critical time.

"Poland is now like one big Lviv," she said, referring to the fact that Lviv is now a refugee center for people fleeing Western Ukraine.

However, I am not sure who should be thankful – them or us. Who is really saving whom? From my perspective, migrants (or nowaks) are the real change that forces Polish society to re-evaluate. Thanks to artists from abroad coming to Poland, especially from Ukraine and Belarus, the Polish artistic community had to wake up from its own, not fully realised, nationalist dream and learn empathy and solidarity. We are, of course, at the beginning of this process. I do not know how long the enthusiasm for solidarity in Poland will last. Another problem is the segregation of migrants. While refugees from Ukraine are welcome in Poland, refugees of a different nationality or of non-white skin color are not. But in the case of the Polish art scene, the Rubicon has been crossed. Now, we cannot take back the hand we have given to our brothers and sisters from abroad.