Culture and censorship in Cuba

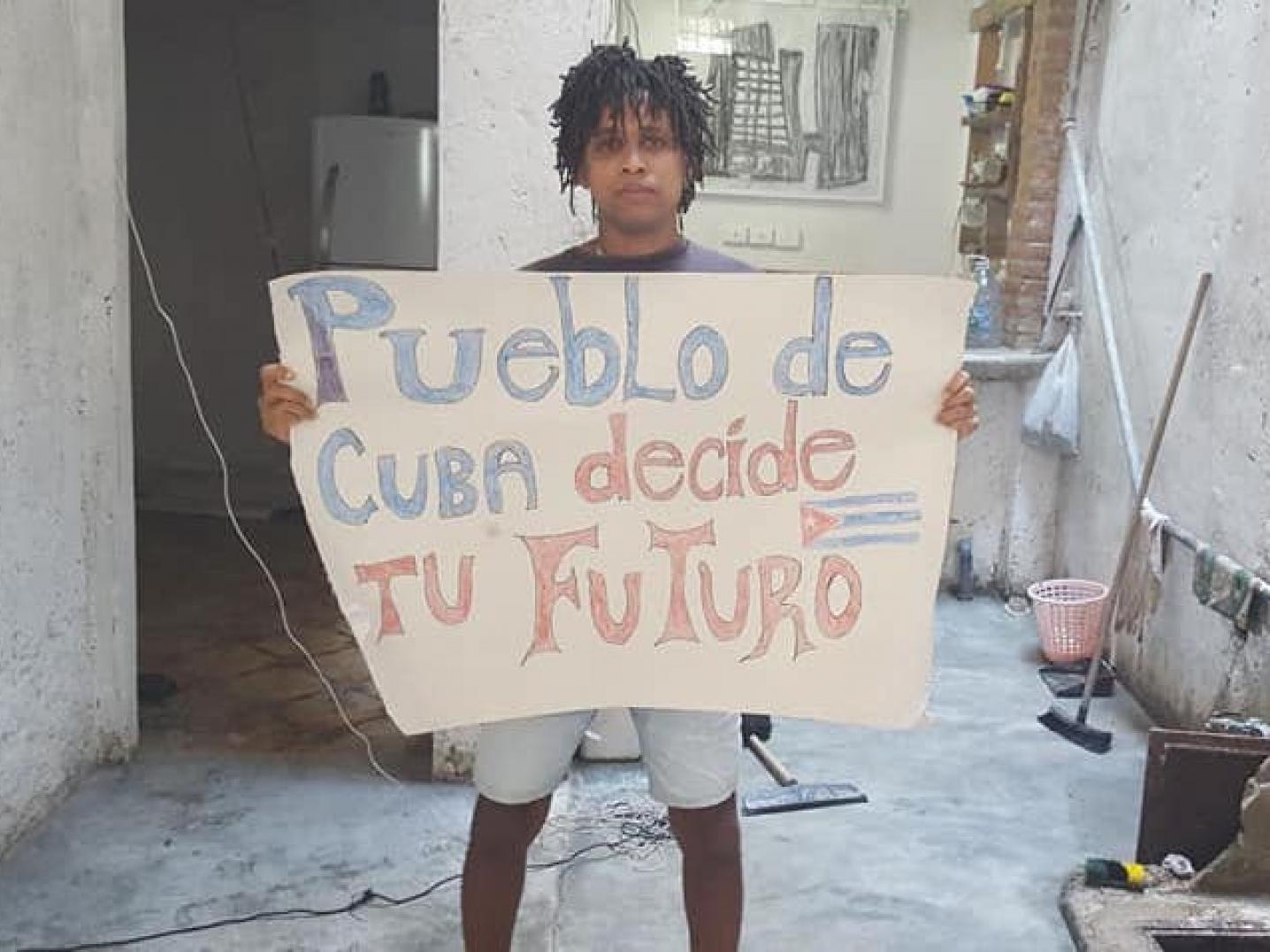

Cuba’s cultural sector is on the move. Hundreds of young Cuban artists were out in the streets in November to protest against restrictions of their artistic freedom. The unrest began after rapper Denís Solis was sentenced to eight months’ imprisonment for streaming the invasion of his home by a police officer on Facebook. In protest against his arrest, eight members of the San Isidro movement (named for the eponymous district in Havana) began a hunger strike. When the police forcefully ended the protest and arrested several members of the group, hundreds of artists marched through the streets on 27 November. At two o'clock in the morning, following protracted negotiations, the demonstrators and Vice Minister of Culture Fernando Rojas announced a compromise in which the Cuban government agreed to cease the intimidation of independent artists.

In Cuba, protests and negotiations normally take place in back rooms, via trade associations controlled by the government. The fact that so many people are now publicly speaking out against the restriction of artistic freedom in general is undoubtedly of historical significance. And that the government has shown a readiness to negotiate with the protestors and has even agreed to a compromise is no less remarkable.

In the same month, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced that Go Cuba!, an incentive scheme for independent young filmmakers in Cuba, would be renewed for another three years. Raymond Walravens, the founder of Go Cuba! and director of Rialto, a cinema in Amsterdam, brings us up to date on Cuba’s cultural sector and reflects on the main promises and challenges of cultural collaboration with this island country.

A land of opportunities

Walravens’s interest in Cuban cinema was initially sparked by a new generation of filmmakers from non-Western countries in general. The rise of this new generation went hand in hand with the rapid development of digital film and editing technology, which has greatly increased the democracy of the medium of film: “With the arrival of the digital camera, making films has become much cheaper and much more accessible. Using a cheap camera and downloaded editing software, just about anyone can make a film. Thanks to that democratisation, things are happening there that I haven’t seen in Europe for many years. A new generation of young filmmakers has emerged over the past twenty years, and they are trying to find their own ways of telling stories.”

One advantage that Cuba has over other non-Western countries is its unique combination of favourable production conditions and good facilities. For example, Cuba plays host to the most important international film festival in Latin America, the annual Havana Film Festival. It is also home to many high-quality art schools, such as the renowned International School of Film and TV, founded in 1986 by Columbian writer Gabriel García Márquez and Cuban filmmakers Fernando Birri and Julio García Espinosa. According to Walravens, such a well-developed infrastructure is typical for communist regimes, which tend to rely heavily on film as a mode of communication and art form. As a result, Cuban artists are often cinematographically skilled, and many graduates go on to have successful international careers. Despite being a small country with few financial resources and poor Internet connections, this has made Cuba into one of the leading Latin American countries in the area of film, and one that can hold its own with respect to the rest of the world.

“Also,” Walravens explains, “wage costs in Cuba are very low: where a full-length feature film would cost at least €800,000 to make in the Netherlands, in Cuba you could pull it off for less than €100,000. This combination of good production conditions and low wages means that you can make a big splash for relatively little money – especially in the area of independent cinema, which isn’t subsidised by the government.” During Walravens’s first visit to Cuba with his colleague Olivia Buning in 2013, the subject came up while talking with the Dutch ambassador, and this inspired the idea to establish Go Cuba! Since the first application round in 2015, the fund has supported 54 film projects. The selected films are screened at the World Cinema Amsterdam festival, from where they regularly find their way to other international festivals, for example in Rotterdam and Toronto.

Censorship

The purpose of Go Cuba! is to create opportunities for Cuban filmmakers to independently produce works and present them internationally. However, international cultural collaboration with a country like Cuba does pose numerous challenges, Walravens says. “We want to evaluate applications based on their cinematographic quality and relevance for Cuba, but we don’t want to impose European standards. You can avoid this to some extent by allowing makers to submit applications in Spanish and emphasising that they should write their applications not for us, but for their own country and local environment.” According to Walravens, films that express a local urgency often turn out to have a worldwide appeal: “We are looking for local films with universal themes, not some kind of co-production between Cuba and Europe.”

Another challenge when working in Cuba is censorship. Walravens emphasises that the censorship rules are never entirely clear. “The censoring is done by officials, who try to anticipate what their bosses want. In other words, it’s a matter of interpretation, which is sometimes stricter than necessary, and at other times it isn’t strict enough. So at every edition of the Havana Film Festival, you’ll see films being cancelled or moved to a small room somewhere in the back, even though they initially made it through the censorship committee.”

According to Walravens, the Cuban authorities are constantly having to balance the desire to stay in control with the awareness that Cuba has no future if authoritarian policies cause young and highly educated people to flee to other countries. The censorship rules are therefore not set in stone but subject to an unpredictable process of interpretation and negotiation. Nevertheless, Walravens does recognise a pattern in this erratic dialectic of power. “What you see is that the authorities take the status quo as a starting point and then look at what the people desire. They then analyse whether giving the people what they want would compromise their position. With that in mind, they sometimes relax control a little to see how that plays out, and whether any further steps can be taken. However, they are just as likely to make a U-turn and tighten the reins again. You might feel like there’s a bit more latitude one day, only to be disappointed the next. Every relaxation of control always goes hand in hand with a tightening. There is the occasional small step towards more freedom, but then the authorities insist on maintaining strict control. For example, when Internet access became legal, search engines were initially prohibited, making it completely useless.”

Walravens has noticed that these negotiations intensify around important political events, such as transitions of power. “Thus, when the current president took office, a new constitution was announced in which artists were designated as an accepted profession who were allowed to earn money. At the same time, however, that same constitution created a host of compulsory permissions and procedures to be allowed to produce or display a work of art. Artists and the government are locked in a game where the artists are constantly trying to stretch the rules and find loopholes, while the government turns a blind eye right up until it suddenly doesn’t.”

Engagement and resistance

As the recent protests show, the government is not the only party to actively engage in these negotiations; the artists are just as eager. According to Walravens, many young Cuban artists have a strong sense of responsibility, solidarity and social engagement. In his view, many Cuban filmmakers do not merely make art for the sake of art, but are also motivated by a strong sense of social responsibility. “What I often find so dull in European cinema is that many makers are not really driven by a compulsion to create – they already have a home, enough to eat, a family. When they manage to come up with a good plan, they are provided with funding to carry it out. Which on the one hand is wonderful, but on the other hand, it does stifle creativity. In the European setting, you really have to be very idiosyncratic to stand out. But in Cuba, creating things is the only way to survive as an artist: you have to show who you are and what you have to say. That’s why many independent Cuban films are not about ideal dream worlds, but about cold, hard reality – and films like that have much more to say about society than the escapism of certain European artists.”

In Cuba, then, there is a strong contrast between the censorship of the government and the social activism of art. According to Walravens, the current protests in Cuba are a unique expression of that contrast, because they occurred publicly and spontaneously and are on behalf of the independent cultural sector as a whole. The government’s willingness to negotiate with the artists and to reach agreements is therefore a remarkable step, says Walravens. “Although there is no way of knowing how this will develop in the future: three steps forward today may well be followed by four steps back next month. There’s no way to predict that.”

It is not just the protests that are interesting, but also the artists’ resistance practices. Walravens describes how, in Cuba, many artists push the boundaries without actually crossing them. “Cuban artists are always trying to determine what is and is not acceptable, constantly discussing and probing the limits. They certainly attempt to address topical issues, but in a way that everyone can understand what is being said, without provoking governmental intervention because, officially, no rules have been broken.” One such example, says Walravens, is Carlos Quintela’s feature film debut La Piscina (2012), which follows a group of children receiving daily swimming lessons at an outdoor pool. “The world outside the swimming pool is not actually shown, but the film nevertheless talks about what is going on there.” Quintela’s second film, La Obra del Siglo (2015), uses a similar implicit strategy, presenting a narrative about a failed Cuban project to build a nuclear plant in partnership with the Soviet Union. The story takes place in the village built around the now dilapidated plant and follows the lives of various men from the village. Through dialogue and cleverly selected archive footage, Quintela manages to express his engagement with a prohibited subject, but only suggestively so.

The promise of international collaboration

Our discussion with Walravens yields an interesting and perhaps unexpected insight: even more so than for other countries, international collaboration is vitally important for the Cuban cultural sector. Since independent Cuban filmmakers can produce high-quality films with relatively small budgets but are entirely dependent on foreign funding, international collaboration can have a substantial impact on the critical Cuban arts. Films created through schemes like Go Cuba! are screened in various places across the island, allowing makers to strengthen their local position, to gain a local audience, and to become more readily eligible for state funding. But such independently produced films are often also shown worldwide, giving makers the opportunity to travel abroad and exchange views with different audiences. This combination of local embedding and international experience reduces the artists’ reliance on the state and, as a result, allows them to become more outspoken with regard to the state. Which is what we have been seeing this past month: artists daring to speak out and to take part in protests.

Just as local urgency can have universal appeal, international experience can empower artists locally. In that way, it is not at all unthinkable that, despite all the challenges and risks involved, the promise of international cultural collaboration may well promote the emancipation of Cuban artists. Go, Cuba go!