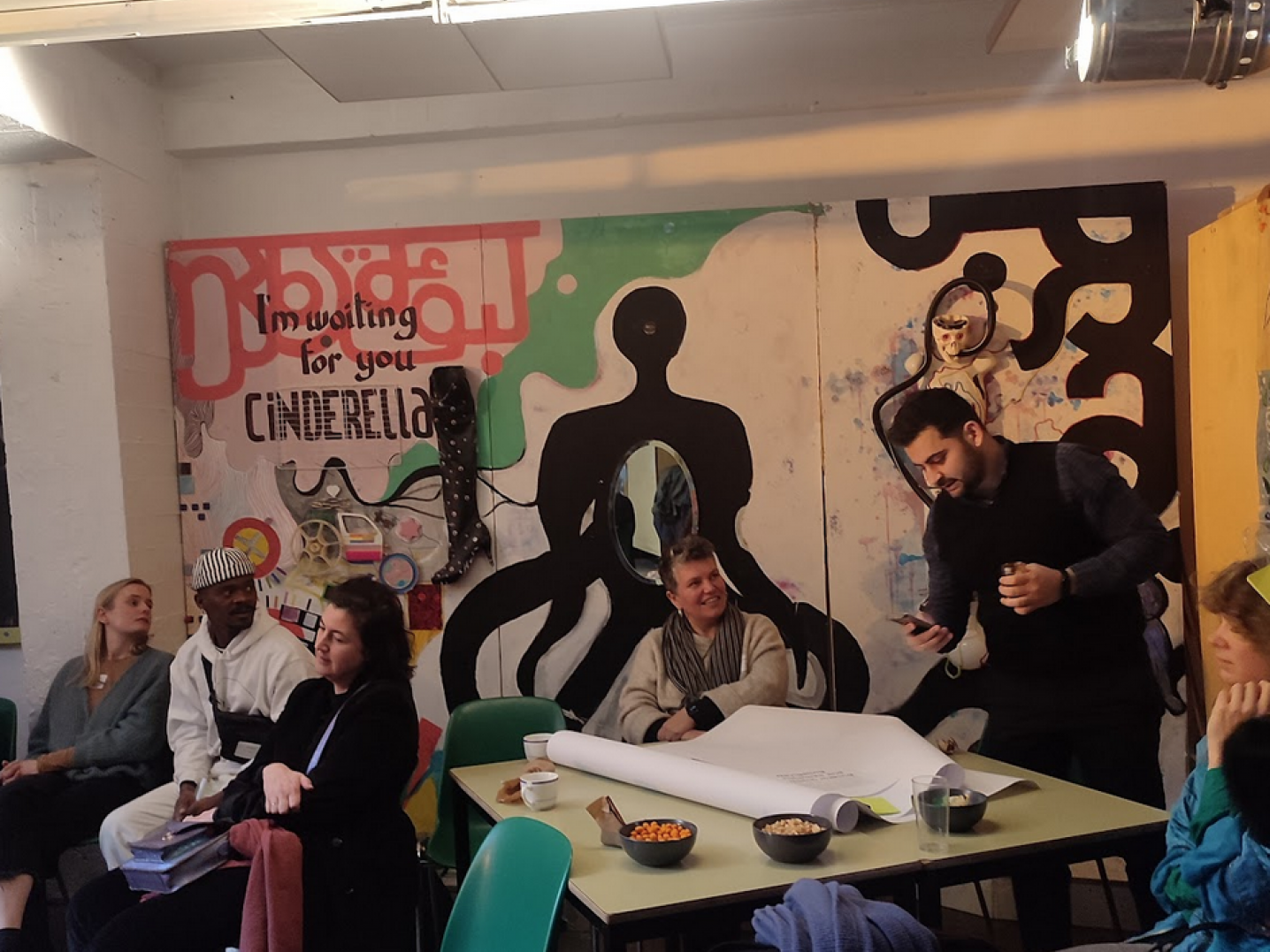

As part of its event Future Hospitalities, Exploring New Forms of Hospitality through Cross-sectoral Exchanges, DutchCulture | TransArtists and the Flanders Arts Institute invited cultural and humanitarian workers from Flanders and the Netherlands to explore the needs, challenges and practices of hosting forcibly displaced artists and art workers. Rather than offering an objective report of this event, this article is a collection of subjective impressions resulting from the conversations and debates that took place over the course of the day.

The first part presents ideas and concerns raised at the meeting that strike a sensitive chord, introduced by statements by participants from various working sessions. The second part is an attempt to formulate concluding thoughts and to sketch a few ideas to consider while trying to answer the event’s principal question: how can the cultural field be better prepared and permanently open to professionals who are forced to move?

1 – Thoughts on hospitality

There are always a few allies you need to get on board

Unpacking the notion of hospitality and its evolution, DutchCulture and the Flanders Arts Institute chose to bring together a broad spectrum of actors. Participants included representatives of arts venues, activists, humanitarian workers and artists, working in the public sector or civil society. The event gathered those motivated by their own experience of exile, those seeking to share knowledge and experience of welcoming newcomers, as well as those who wish to deepen their own understanding of what should and can be done. This emphasis on diversity turned out to be a key element: it laid the foundation for a conversation whose starting point was our responsibility as engaged citizens, rather than that of actors speaking from their field or discipline. Although our roles might be different depending on our position and sector, what Future Hospitalities strongly affirmed is that this conversation has to take place between many different actors, with a multiplicity of voices and the exchange of many experiences. Occasions, when a conversation can truly happen within an audience speaking from diverse perspectives, are still relatively rare and always mind-expanding.

Don’t ask how to overcome the barrier of language, but how to embrace it

Beneath the shared interest in enhancing and renewing our hospitality efforts, the question of language quickly emerged as a hot issue. It is a complex challenge to tackle: while international English often feels like a practical - if not always comfortable - compromise, the use of a single language (whichever it is) remains an instrument of exclusion. Navigating between inclusivity and practicality is all the more exacerbated when seen from the perspective of a country like Belgium, where language was one of the key defining elements of the current state structure and where linguistic emancipation remains a source of heated political debate.

Furthermore, language is more than a simple choice or a common agreement: in the words of one of the participants, David Ramos Joao, “one of the biggest difficulties in migrating is the vocabulary; not only language but communication in general”. Joao here refers to the common cultural and communication codes that define social and work relations and that infuse the organisational models and practices, beyond the mere practical choice of a language. These codes are complex and evasive, as they are often tacit and implicit. We are so comfortably immersed in them that we often don’t even realise what they are.

To welcome newcomers is also to put a spotlight on those common codes, to notice them, question them and put them into perspective. This is an enriching process from which organisations and people can learn immensely. In light of this, the choice of topic for one of the working sessions was particularly pertinent: Embracing Broken Languages. 'Broken language' or, more broadly, a step away from commonly shared ways of talking and doing, can also carry the potential for a different perspective, for learning and growing together. If we recognise its positive aspects, 'broken' language is valuable and should be cherished.

Slowness gives time to connect

Hand in hand with the question of language comes the issue of time and space, as resources that organisations can offer in their effort to welcome newcomers. Fameus’s 8-step plan, designed to help cultural organisations become more accessible to newcomers, offers a valuable example. The steps concentrate on the most effective use of available resources, and on refocusing the hosts’ attention to the specific context of the newcomers. Advice such as 'focus on multilingualism instead of on foreign languages' or 'create an environment of trust, security, warmth and respect' might seem somewhat obvious. Still, they shift the attention towards the essential in powerful ways.

If we really want to be accessible hosts, we need to focus on the needs of the people we are welcoming – which might mean changing our ways of working in unexpected ways and opening up to a necessary 'mentality change', as mentioned in a few working sessions.

There is much to learn from the experiences of practices tried out around the world. Can we imagine introducing mandatory emergency guest rooms in every house or building? Could we introduce hospitality protocols for the cultural sector (similar to the mandatory disaster training in Japan)? Might we implement our hospitality practices by means of artistic methods, such as improv acting? Most ideas and examples call for a shift in the mindset and focus within the organisations themselves. To truly be able to serve the needs of newcomers and contribute to a more welcoming society, it is necessary to create time and space for the needs to be understood, for the connections to happen, for the host to learn and adapt, and for trust to be built. It is necessary to slow down so that these processes can evolve.

“If we slow down, we open up opportunities to be more reactive,” was mentioned in one of the groups. To unlock doors and welcome newcomers is to resist the omnipresent acceleration and growth mentality and to create a safe space and sufficient time for processes to grow.

2 – Avenues to explore

Planning instability

In the relative comfort of the Western cultural sector, when we talk about crisis, we are mentally in a space that lets us conceive of the present moment as an anomaly, as something to endure, to resist or actively repair so that we can go back to the comfortable world of familiar routine. Back to the 'normal life' from before the crisis. Looking back at the years behind us, with the endless succession of one crisis after another, we may wonder whether this perception still holds… As our colleagues in the East and South know only too well, to work in the cultural sector is to navigate an uninterrupted string of crises that perilously stretch the limits of organisational and personal resources.

Perhaps it is time to accept that the crisis is our normal and to let go of the hope that we will one day reach calm waters (as soon as we finish dealing with the current storm). If we truly accept this insecurity as forming an intrinsic part of our reality, what would we do differently? In a world that is perpetually challenging the systems and models on which we build our work, what organisational models, what skills and what knowledge do we need? How should we organise our work, distribute our resources, build relations and use time and space to best navigate this reality?

Learning from others

If we could accept our reality as fragile and ever-changing, perhaps we would be better equipped to face it. More than ever, it seems urgent to create alliances and to learn from colleagues from more precarious contexts, such as those in Eastern Europe and the Global South; from those that for decades have been confronting instability and insecurity and building creative collaborative strategies of survival. In Croatia, the independent scene has created Pogon, a new type of institution based on a civic-public partnership. In Palestine, the Rawa Fund is experimenting with a funding model based on collective community decision-making. In Uruguay, NIDO has proposed a meeting of contemporary performing arts practices outside of all structures to share knowledge in non-hegemonic ways. The examples are abundant.

We need to learn from those experiences, not just because we strive to be good hosts, but also (perhaps more egotistically) because the future of the sector depends on our adaptability and our capacity to rethink our organisational models to better suit today’s world.

Being more open, more curious, more inclusive

When Russia launched its war on Ukraine, the reaction of the arts sector across Europe was immediate and strong. Many arts organisations expressed their support, opened their spaces to Ukrainian artists, hosted Ukrainian art workers, and adapted their programmes to focus attention on the tragedy of war and the need for solidarity and resistance. Many theatres, festivals and concert halls rushed to adapt their programmes to include Ukrainian artists and to reach out to Ukrainian colleagues to welcome and to help them, and to collaborate. What is happening in Ukraine is tragic and has prompted compassion, empathy and support throughout Europe. The cultural sector has, by and large, proven that it is capable of swift, coordinated acts of solidarity.1

This gesture of solidarity quickly exposed a more systemic concern: if we are to include Ukrainian artists in the programmes and afford them visibility, we need to know them. We need to know the artists, their artistic interests and their work; we need to understand their context and have a clear idea of how their artistic gestures will resonate with our reality. Can we, members of the Western European art sector, genuinely say that this is generally the case? To put it more directly: the war and the subsequent exodus of Ukrainian artists and art workers once again revealed the collaborative imbalances in Europe. As Western European art professionals, how many Ukrainian artists did we collaborate with, or simply know of, before the war? How many Ukrainian projects did we see on Western stages in the recent (or not so recent) years? How many Western performing arts professionals (besides a few notable examples) know and understand the context in which Ukrainian artists work, their concerns, challenges, their artistic interests and needs? The answers to these questions do not look flattering, as, with all due respect to a few notable examples, our general knowledge of the Ukrainian art scene did not amount to much more than that of, for example, the Syrian scene.2 This has undoubtedly impacted our capacity to respond to the crisis and to welcome and include Ukrainian artists.

If we are to become better hosts, perhaps the first step would be to become better neighbours. This implies that, as cultural professionals, we become much more curious and open to non-Western colleagues, and much more attentive to artistic developments and practices that are not our own. And we should do so before the next crisis hits us and we realise that we’ve been navel-gazing for too long…

Sustaining solidarity

In its short study In Search of Equal Partners, Culture Action Europe looked at the inclusion of artists and cultural workers from South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) in the European cultural sector. One of the findings is that those who were once newcomers fleeing war and conflict and in need of hospitality, today remain “locked between unfavourable systemic pre-conditions and systemic discrimination and stigmatisation”. It is disheartening to note, as the study shows, that the cultural sector across the EU has not been able to fully incorporate SWANA artists and art workers within their ranks, and has failed to benefit from their creativity and competence: “While they see themselves as a part of the global cultural and intellectual force in the face of wars and inequalities, they still find themselves treated as recipients of narrow and rigid integration policies or a form of solidarity that can resemble charity.” Sustaining solidarity and hospitality over a longer period of time is a real challenge. The first line of support in a situation of crisis is essential, but the effort cannot stop there. We need to find ways to permanently and continuously include newcomers in the institutions, practices and decision-making bodies of the host cities and countries, not simply to help them continue their careers, but also for the benefit of the arts sector hosting them.

From this perspective, the experiences and resilience strategies of newcomers become crucial competencies that we can learn from and build on. Beyond being good hosts, we need to accept and appreciate that we are building a common future together with the artists and art workers we welcome, and that, with a view to this future, we are ready to learn and change.

Endnotes

1. One would like to think that, as a sector, we have learned a lot from the recent years of other wars and conflicts such as those in Syria and Afghanistan; that our swift and generous outpour of solidarity is the result of this learning, and not of some problematic division that make certain tragedies more physically or culturally “closer” and therefore more urgent.

2. Which, incidentally, dismisses the argument of the ’geographical proximity' of Ukrainian culture that some advanced to justify the much more modest mobilisation concerning some other conflicts and wars.