In this series of interviews with a young generation of makers, five young artists from different disciplines reflect on their artistic practice, collaborations and their future ambitions. A central question is: how does this new generation of artists make use of technology, digital platforms and social media? In this third and last article we introduce Niek Vanoosterweyck (Antwerp, 1997) graduated in Mime at Academy of Theatre and Dance in Amsterdam in 2020, with his performance installation TANZMANSCHINE.

Vanoosterweyck was planning on going on tour with this performance, when the pandemic broke out. The cancelation gave him the opportunity to re-examine and re-interpret TANZMANSCHINE, resulting in a digital registration of the performance, which premiered at re-CONNECT graduation festival in the summer of 2020.

To escape or to fight

Vanoosterweyck rather calls the digital presentation of his work ‘a digital version’, which he carefully constructed together with cinematographer Pieter Vandenhoudt's team of technicians Titus Duitshof and Hessel Hilgersom, dramaturge Saskia Wieser and music design by IGNOTA. In the 45-minute film, the spectator watches Vanoosterweyck caught in a 5 by 5 metres square cage of steel, light and sound. The installation is structured by scaffolding tubes and divided into nine squares of light on the ground.

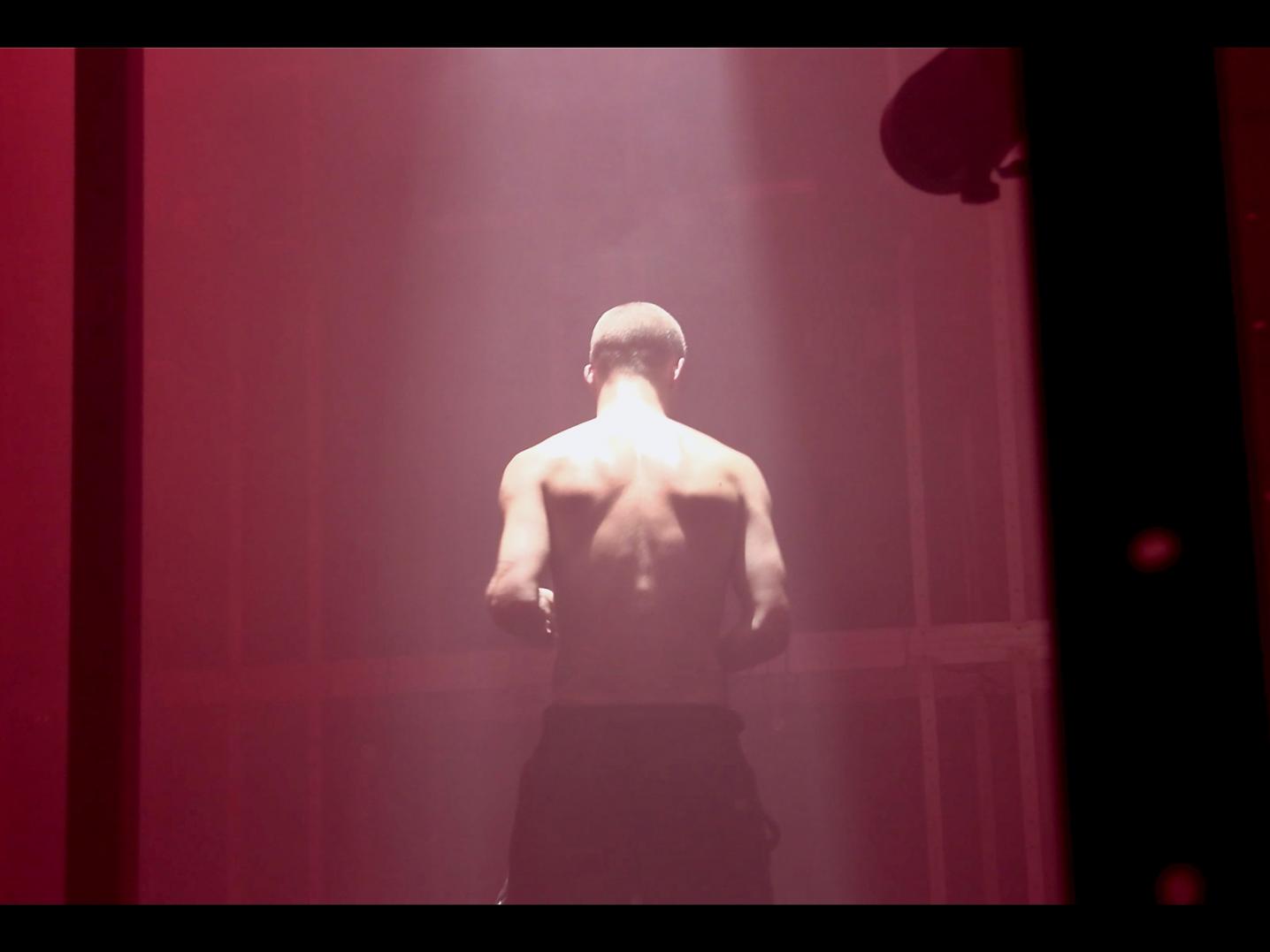

It starts with a red lighted square in the middle of the picture and the shape of a body on the foreground. After a few moments, the sound swells, as the light fades away. In the next shot, Vanoosterweyck is standing like a boxer in the middle of a ring of light, preparing himself for some sort of fight. The light, sound and structure of the square form a system and the purpose of the performer is to escape, fight or influence this system. “This system that I have to overcome I find more interesting than composing a narrative; words can say a lot but actions even more,” he says.

Being an avatar

Nevertheless, some sort of narrative in TANZMANSCHINE can be unravelled. The machine is like a big, evil world by which the protagonist is suppressed. It reminds of video games aesthetics, rave culture and techno scene. The choreography is partly inspired by ancient martial arts. Vanoosterweyck acknowledges this: “It was like being an avatar. It feels so powerful to play with this machine, but it was also rather intense. I was jumping 120 BPM around these 1,5 meters squares for 45 minutes.” This physical exhaustion is visible in the second half of the registration. For Vanoosterweyck, the challenge was to actually fulfil a physical act that people expected to be impossible. “It’s my thrill to prove that I can do it, without revealing exactly how.”

But Vanoosterweyck is willing to explain to us how the system works: “An infrared camera projects invisible light on my body from above and is connected to Isadora, a communication software. In Isadora, the incoming data is transformed into light and soundscapes. Every act or movement has its consequence but cannot be directly traced. You feel the technology is there, but you cannot see or touch it.”

In the digital version, the suggestion of a three-dimensional moving system is given by compositions and overlays of top-down shots and shots of the performer’s body from different angles. An image of flashing lights of cables in the back of an unidentifiable electronic device, reveals the fact that the entire light and sound system was programmed in detail before Vanoosterweyck entered the cage.

Interdisciplinary approach

The work was created at the IDLab of Academy of Theatre and Dance. At the beginning of the semester, students from various studies get the opportunity to do a two-week course called the ‘Machinery’ to learn how to work with all the devices and technology provided in the IDLab. A few years ago, the ATD invested in state-of-the-art hardware, electronica and software. Now, professional theatre companies from all over the country want to make use of this equipment. Head of the interdisciplinary lab Erik Lint tells his students to start thinking from the impossible. “What would you like to make that is never going to work?” he asks, to assist with starting their creative process but also to make students conscious about practical possibilities and issues that might arise throughout this process. What do they need to realise their ideas? Whose expertise is needed? IDLab is all about interdisciplinary collaboration.

The technological systems and devices, service and assistance IDLab provides are not accessible for all 800 students. Whoever wants to make use of it, must apply with an extensive project proposal in which they motivate their need for the space, facilities and assistance just like they will be doing once graduated and working as a professional.

Besides the time pressure of the tight schedule at the IDLab, the Covid-19 measurements made graduating even more complex. “During the last semester, educational institutions were mostly closed. Only a hundred people were allowed in the building, so we had to facilitate our own rehearsing space. I figured: nobody is going to help me, but me. It doesn’t matter whether it’s now or next year, I have got to do it myself. At school they promote the idea of uniting in a collective after graduating, because together you’re stronger than alone. I hear that, but I rather work democratically in a multidisciplinary team in which everyone has his own responsibilities.”

Within today’s performing arts sector, many young actors are also presenting themselves as directors or filmmakers and vice versa. Vanoosterweyck thinks the tendency of “everyone doing everything” decreases the quality of the work. “I chose to do mime and I will develop myself as a performer, as a maker and an entrepreneur within that niche. I am good at what I do, but always question what can be improved. As an artist you need to have an ego in order to independently create something, but it’s also important to keep your feet on the ground.”

The digital work of Vanoosterweyck might seem far off from the traditional practice of mime, but according to the artist it’s not: “Mime always centres the body. It’s about playing and moving within the moment, exploring your body and the surroundings in an almost childlike way. Another core concept of mime is the dramatic effect a counterforce against a movement or gesture. In TANZMANSCHINE the light and sound offer this counterforce.”

“It annoys me that I’m not skilled enough to do the in-depth coding and programming myself. But I know it’s my job to ask the questions and to discover or create a system between the movements and technology,” he says. By forming systems of agreements, then questioning and challenging those through technology, Vanoosterweyck keeps in charge of his own concept and work and is able to collaborate on equal grounds with light- and sound designers and technicians.

Controlling light and sound

Despite his critical position, Vanoosterweyck speaks full of praise about the skills he acquired at IDLab and his supervisor Bas van Rijnsoever, who motivated him to continue his research after graduating. He started researching dance notation and movement analysis by Rudolf Laban and Joan Benesh, who laid the foundation of 20th century human movement theory. This helped him to develop a framework of noted choreography which can be translated into a technological system, that can be coded by a professional.

During the second lockdown in the winter of 2021, Vanoosterweyck temporally moved to his hometown Antwerp, because unlike the Netherlands museums were still open in Belgium. Supported by The City of Antwerp and arts platform Fameus, Vanoosterweyck created an interactive installation called TANZ IN 44, which was featured at FACTOR 44 in Antwerp in collaboration with BOX22 Artspace. During the last weekend of March and the first of April 2021, visitors were able to step into the installation themselves, with a maximum of two others. With their movements they were able to control both the light and sound and examine what consequences their actions had. Through this interactive version, the division of roles between the performer and the spectator were blurred. “Most of the people who entered the installation, made the same movements as I did in response to the coded light and soundscape that was leading their actions.”

Learn from the body

The educational side of the TANZ IN 44 installation might grow in the future: “I want to share my skills with other people and also learn from them,” he explains. After establishing a foundation and studio in Amsterdam, he would like to create a portable and open source installation that can be used to teach people about their own bodies.

“Technology might offer ways to experience your body differently. The body is capable of understanding a lot, sometimes it’s like a slap in the face. Consciousness about your body and movements will influence the choices you make, just like consciousness about climate change influences the way you travel and eat.” The exact form of this installation is not determined yet. “But I imagine some sort of cube, with instructions that can be downloaded online that help people to formulate a score for themselves and stimulate them to execute this on their own terms.”

Television theatre

Vanoosterweyck is fully committed to the technological and systemic approach of performance, in which he truly believes. “Data will be an inherent part of the performing arts sector, within the next twenty years. In the way technology is used in today’s theatre, technology is not a built-in feature of it but just supportive of the production. But I want technology and performance to really merge and at the same time provide the ‘WOW feeling’ theatre is supposed to give you,” he states.

Throughout the last one and a half year, International Theatre Amsterdam experimented with streaming several theatre experiences. For example, International Theatre Amsterdam in collaboration with VPRO started reading Bocaccio’s Decamerone from an empty theatre at the beginning of the pandemic and posted these video’s online. A year later, in May 2021, VPRO broadcasted an exclusive adaptation by ITA of the entire Roman tragedies on national television. Although theatre purists will probably not agree, critics consider this production – with their advanced cinematographic effects and technical features – a ‘genre of it’s own’.

This tendency of merging theatre, television and technology turns out to be fruitful for young makers like Vanoosterweyck. After editing the digital version of TANZMANCHINE, he submitted the digital version to the national broadcasting company NPO, which agreed to air the registration twice a year on NPO 2 Extra and their online streaming platform. Moreover, because many cultural institutions and theatre companies like ITA invested in technological systems and streaming devices during the lockdown, more venues can offer the needed equipment and space for digital installations he would like to create.

By using open source software programmes such as Isodora, interactive digital art can be made widely accessible all over the world, even without the physical presence or interference of the artist himself. Taking Vanoosterweyck’s educational intention in account, his future work holds a democratising and energising value, bringing people and technology together by making use of data, human movement and experts from various disciplines.