The Flemish-Dutch theatre sector: one language, one tour

One year ago, DutchCulture teamed up with Amsterdam’s Flemish cultural centre De Brakke Grond to launch OverBruggen, a research and change project aimed at streamlining Flemish-Dutch cultural collaboration. A study into the Flemish-Dutch theatre sector in 2018 paved the way for this project. Whereas the study was originally conceived as investigating the cultural collaboration between two sectors in separate countries, it soon turned into an analysis of a single closely-knit field. The OverBruggen project, which included visual arts, music, design and architecture in addition to theatre, similarly revealed intensive cross-border collaboration. A report on OverBruggen is due this autumn. Below you can read more about the process and the results of the study Seeking a cross-border measuring tool.

A (very) broad question

The quest began when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asked DutchCulture to map out in detail the Flemish-Dutch cultural collaboration. Who works with who, who talks to who, and how do the lines run connecting the Flemish and Dutch cultural sectors?

The research team first turned to DutchCulture’s prime asset: the database. Every year and throughout the year we collect information on tens of thousands of cultural activities by Dutch makers and organisations abroad. This produces a quantitative visualisation of the results of the International Cultural Policy, and offers a means to research cross-border collaborations. Yet it turned out to be a bit more complicated with regard to Flemish-Dutch collaborations, as the dataset offered too little clear-cut information. We encountered two problems, in particular.

1. Flemish or Dutch?

It is difficult to determine whether a certain maker is Flemish or Dutch. This is demonstrated for example by (Re)framing the International, a publication by the Flanders Arts Institute, which is an organisation supporting music, visual arts and theatre in Flanders. They had made an attempt in 2016 to map out the ‘Dutch-Flemish exchange’ in preparation for a meeting between Flemish and Dutch theatre programmers during Het Theaterfestival. They compared their data with those of DutchCulture, which revealed a 10% overlap in the datasets. It means that many makers identified as Flemish by the Flanders Arts Institute were also registered in the DutchCulture database. The reason is probably because people can be registered in the database both on the basis of nationality and place of residence.

2. Non-matching data collections

Additionally, the figures for cultural exports from the Netherlands to Flanders were insufficient to ground the research on. We also needed figures regarding cultural exports from Flanders to the Netherlands. The Flanders Arts Institute collects this information for Flanders, but uses a different method than DutchCulture. DutchCulture furthermore collects such information for all disciplines, while the Flanders Arts Institute concentrates on music, theatre and visual arts only. We thus encountered a mismatch between the datasets of DutchCulture and its Flemish counterpart, making it impossible to simply compare them.

The team therefore decided to curtail the research area and to limit the focus to the theatre sector. The lion’s share of the data pertains to theatre performances, and this area also showed the best match between the two organisations’ datasets. However, networks cannot be mapped out solely on the basis of import and export figures. We needed additional research methods.

Mapping the theatre sector

We used two research methods to map out the Flemish-Dutch theatre sector. The first is a method called Snowball sampling, which we borrowed from sociology, while the second – dubbed nodal analysis – is an original creation by the research team. The first method entailed listening to the main players in the field. The second meant that we identified nodes, or intersections, and examined them closely to see what they look like.

Snowball sampling

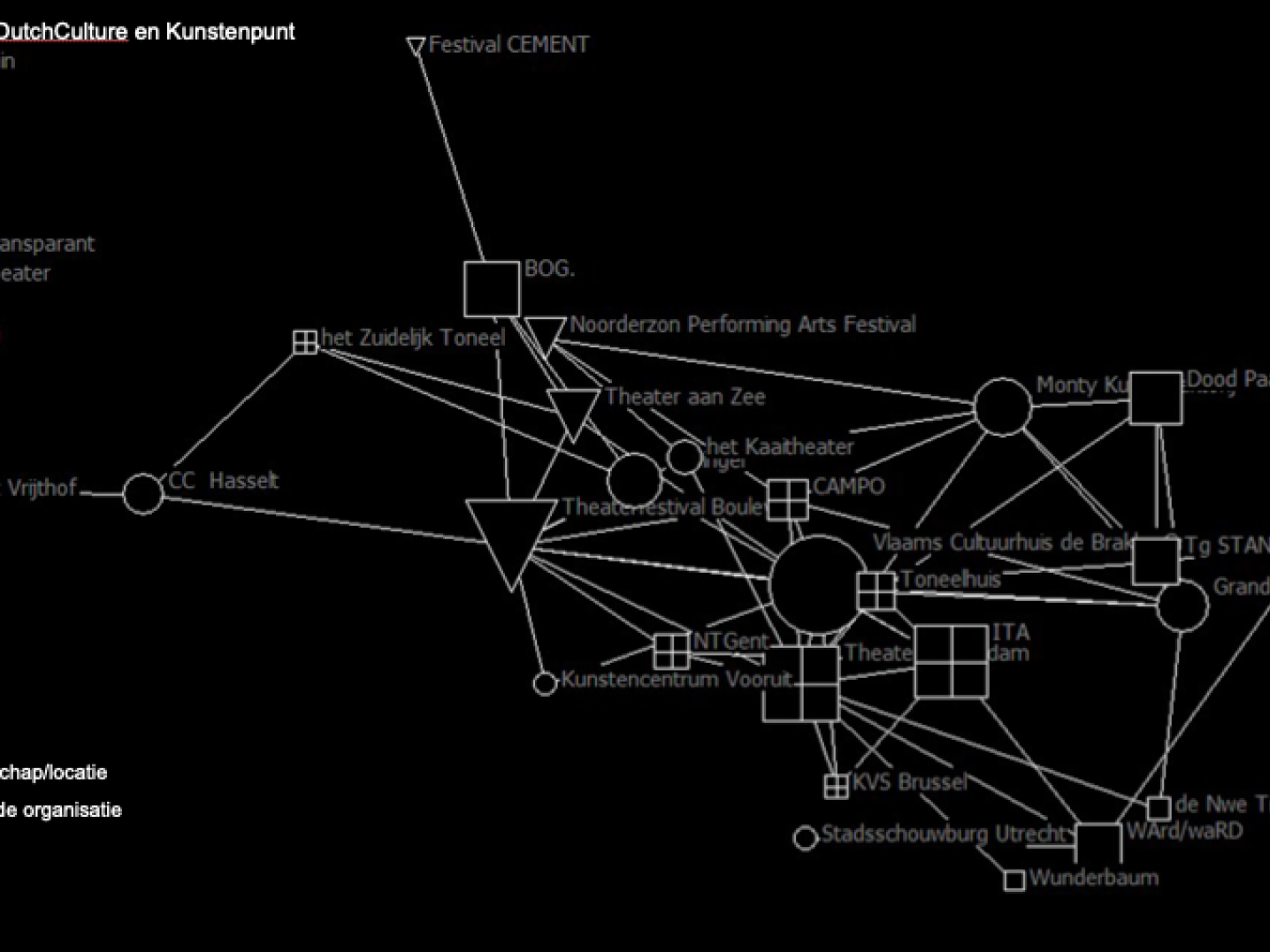

The Snowball sampling method served to identify who works with who in the Flemish-Dutch theatre sector. We asked the twenty most frequently travelling companies and the twenty most visited venues (consisting of 10 Flemish and 10 Dutch companies, and 10 Flemish and 10 Dutch venues). in the DutchCulture and Flanders Arts Institute databases to name their five most important contacts in the Dutch-Flemish field. Diagram 1 shows the top forty players and how they are mutually connected, that is, how often they identified each other.

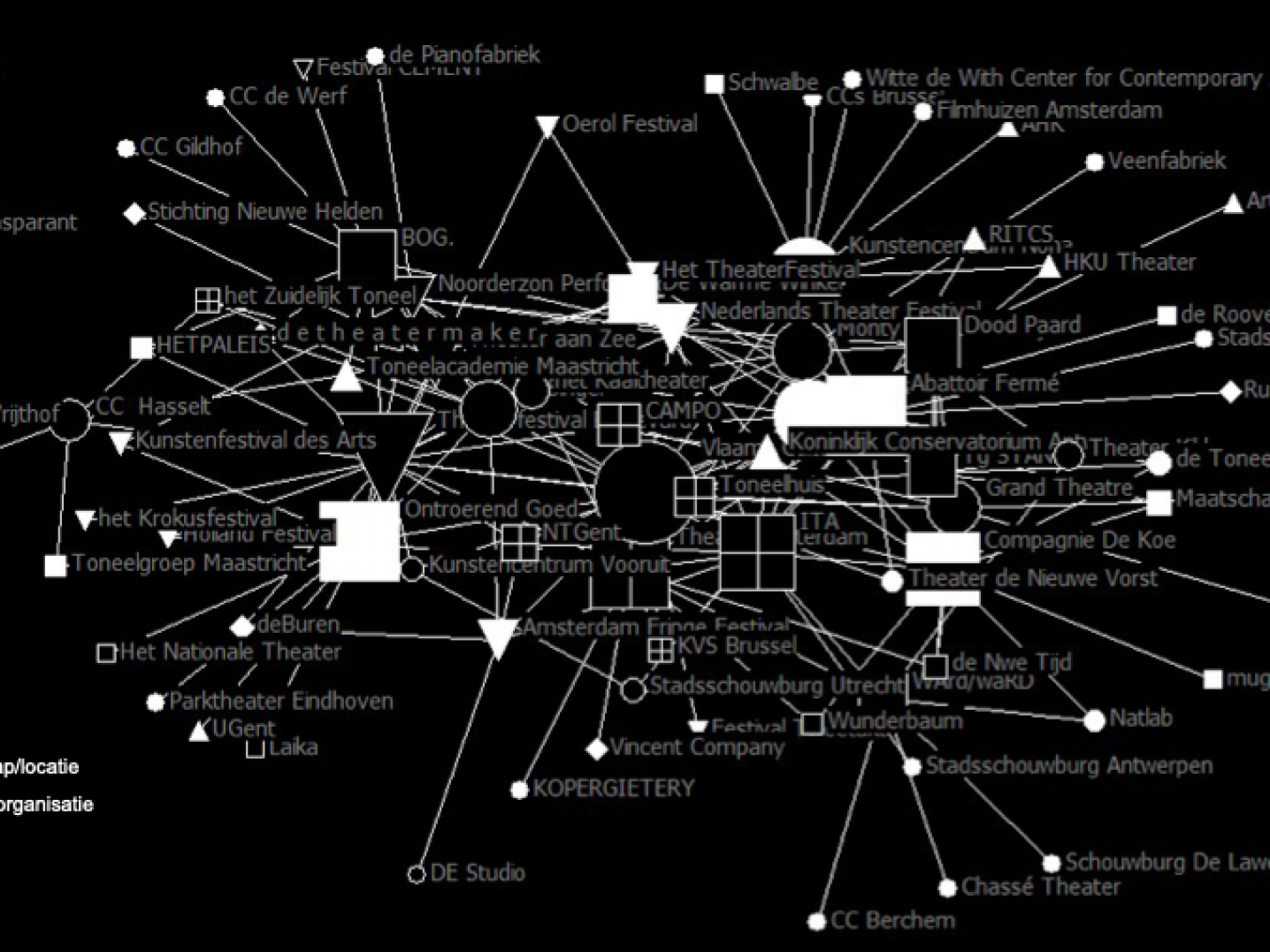

Diagram 2 shows all the contacts identified by the forty interviewed players that were not already part of the top 40. This doesn’t mean that these organisations are absent from the DutchCulture and Flanders Arts Institute databases, but that they are not among the forty interviewed organisations. The respondents for example mentioned a large number of festivals. Festivals appear to be important events since they give new talents an opportunity to perform, programmers can see many different performances within a short space of time, and it’s where makers and programmers meet each other.

This method enabled us to identify the main hubs, or nodal points, in the Flemish-Dutch theatre sector. Most mentioned were Amsterdam’s De Brakke Grond and Monty in Antwerp, followed by Theater Rotterdam, Festival Boulevard, Frascati, Theater Aan Zee and the Theaterfestival. The larger the icon in diagram 1, the more this organisation was mentioned by others. We furthermore found that educational institutes were mentioned frequently. These are entirely absent in diagram 1 (they are not included in the databases because they do not produce cultural manifestations), but they are seen as an essential part of the field by the players.

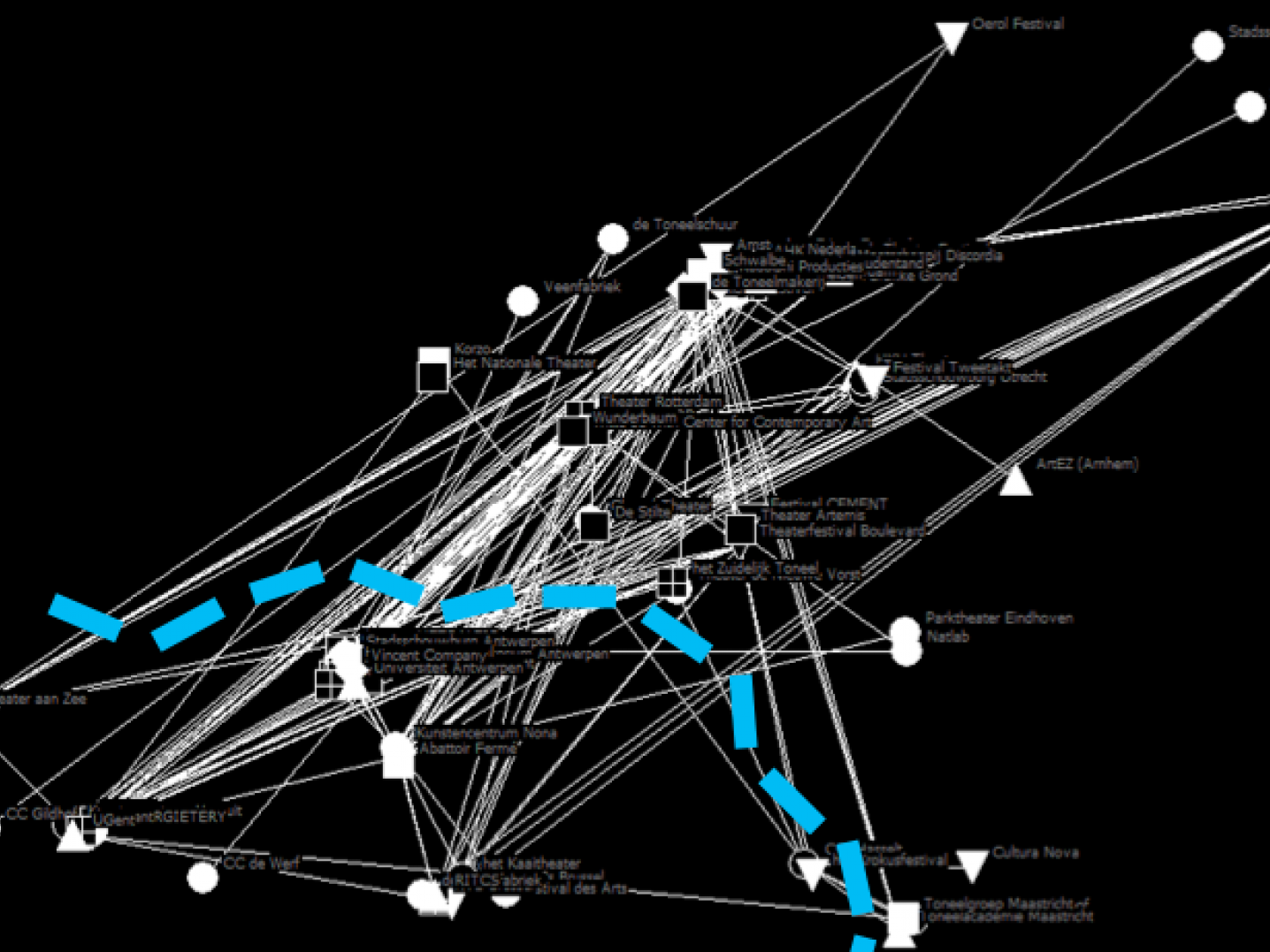

Next, we superimposed these nodal points on a geographical map of Belgium and the Netherlands to determine where the cross-border contacts occur. Diagram 3 shows the geographical distribution of the connections. This reveals that there are lots of lines connecting Antwerp and Amsterdam, but that regional cross-border contacts occur as well. This is clearly visible in the lower right-hand corner, showing lots of connections between Maastricht and Hasselt.

Snowball sampling attributes value and significance to lists of top players by identifying connections and (geographical) nodal points. Yet this method only reveals that a connection exists, without explicating the nature of that relationship. Besides, we only interviewed the 40 top players, so that we actually only measured their particular perspective on the field. This is one reason why we wished to examine the nature of these nodal points more closely.

Nodal points

A nodal point can be all sorts of things: a company, a venue, a production house, a programmer, an educational institute or a festival. By means of nodal analysis we sought to determine how these hubs are composed and how they create or sustain the connection between Flanders and the Netherlands. We therefore cut up the theatre sector into different layers, to then visualise the interconnectedness per layer.

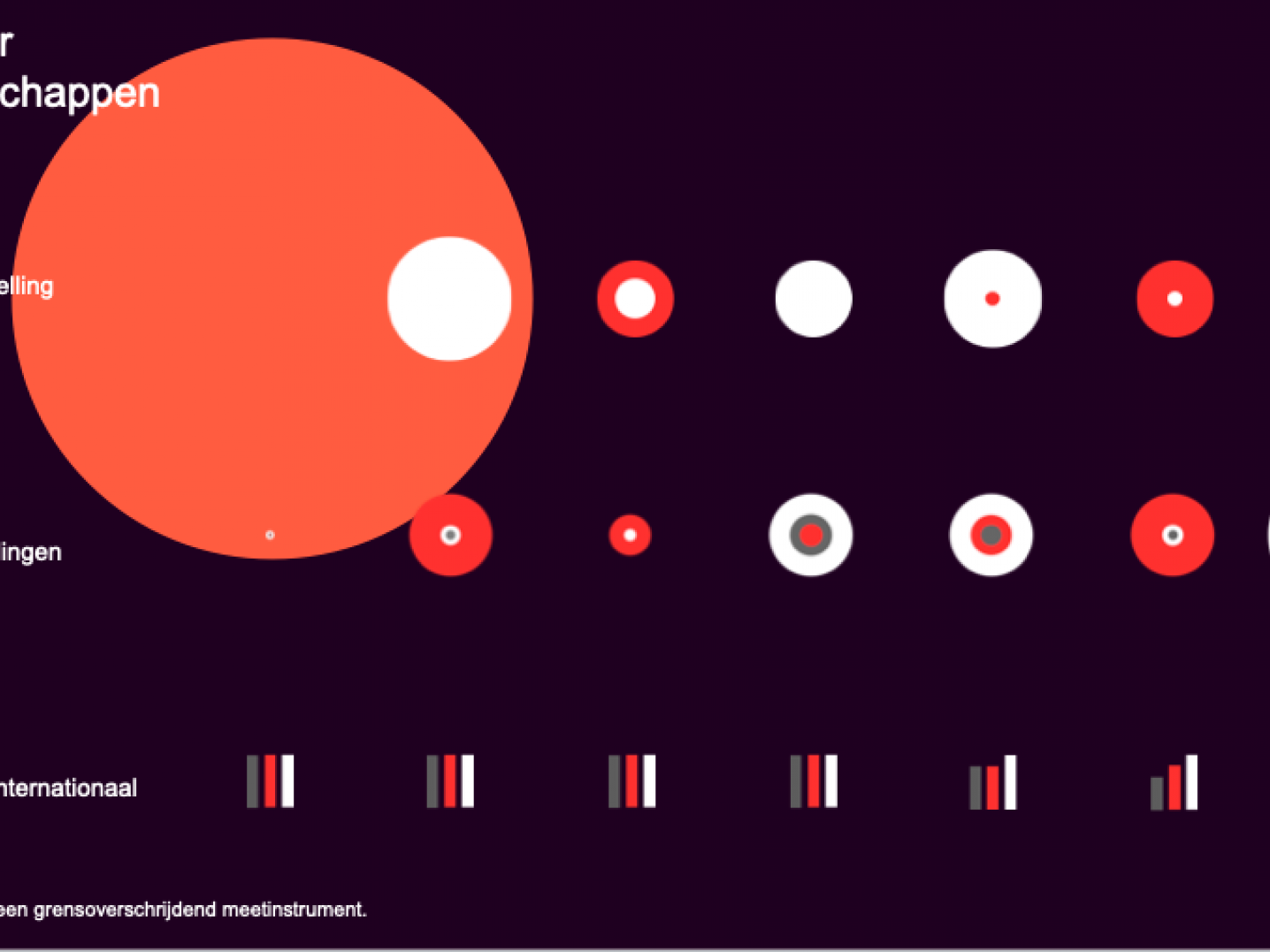

Diagram 4 displays 6 theatre companies, two of which are based in the Netherlands and four in Flanders, showing their Flemish-Dutch composition, where they mainly perform, and how much importance they attach to international performances.

Red represents the Netherlands, white represents Flanders, and grey stands for ‘international’, so neither Dutch or Flemish. Notably, all six companies are of Dutch-Flemish composition. Sometimes just one of the actors derives from the other geographical area, at other times the composition is 50/50. Simply the composition of theatre companies thus reveals the interconnectedness of Flanders and the Netherlands. In terms of performances in the native country (where the company is registered), the neighbouring country and other countries, we see that the Netherlands and Flanders are important markets for each other. Just one Flemish company does not perform in neighbouring Netherlands.

This method effectively visualises how the interconnectedness in the Flemish-Dutch theatre sector not only consists of Flemish and Dutch companies that collaborate or that perform in each other’s territory, but that the interconnectedness can be found at every level in the sector. Flemish actors are part of Dutch companies and vice versa, Dutch programmers are employed by Flemish venues, education institutes show a mixed population, and so on. This does make it difficult to precisely map out Flemish-Dutch collaboration; the sheer intensity of exchange means that we should rather think in terms of a single theatre sector.

'Subsidy fence'

This is precisely what the professionals concerned also told us: “I make just one production, for both Flanders and the Netherlands.” Since it forms a single linguistic area, makers also see it as a single touring area. However, the national border reimposes itself as soon as it comes to subsidy applications. That’s when the makers need to ‘show their colours’, meaning that a maker must choose between residing in the Netherlands or residing in Flanders. Makers do perceive this ‘subsidy fence’ as a formal border.

We thus found that there is interconnectedness at all levels, except where subsidy systems are concerned. We saw previously in our analysis of the field that education institutes form important nodal points. Students easily cross the border to study, they are mobile and in a sense ‘lack’ nationality. The interconnectedness often starts at this level, as makers first meet as students and go on to establish theatre companies together. This is reflected in the composition of theatre companies. The interconnectedness then continues at the level of festivals, where the entire Flemish-Dutch theatre world converges. The contacts established there further boost Flemish-Dutch exchanges. In this way, the theatre sector organically becomes a single entity with numerous cross-border collaborations.

Makers would love to see a Flemish-Dutch subsidy fund, or to see the subsidy systems streamlined, enabling them to apply for subsidies across the border, regardless of their place of residence. In the Netherlands subsidies are granted to theatre companies, while in Flanders it is the venues that receive structural subsidies. Flemish makers in particular have been suffering on account of this for years, due to the comparatively low artist fees in the Netherlands. Thus, despite the close cultural interconnectedness, it remains a situation of two different countries. It won’t be easy for policy makers to streamline the subsidy systems. Nevertheless, the Overbruggen project, which was initiated by the Flanders Cultural Department and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, is attempting to smooth out other wrinkles in the collaboration, with the goal of making Flemish-Dutch cultural exchange increasingly easier in the future.

The study 'Seeking a cross-border measuring tool' was presented at the Cultural Conference 'De Tussenruimte' in Antwerp. DutchCulture worked together with deBuren to organise this conference in the run-up to the 4th Flemish-Dutch summit in November 2018. The research team consisted of Lisa Grob, creative strategic Jurian Strik of Studio Strik and Djamila Boulil. The overall theme of the conference was Urban Dynamics and Creative Entrepreneurship.

Find more information about OverBruggen here.

Check out the complete overview of Dutch cultural activities in Belgium in our database. If you are a cultural professional who wants to go to Belgium, feel free to contact our Belgium advisor Renske Ebbers. For funding possibilities, check out our Cultural Mobility Funding Guide or the websites of our partners Mondriaan Fund, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Performing Arts Fund and the Dutch Embassy in Brussels.