Kiriko Mechanicus' (1995) keywords (not necessarily related to each other): history, food, documentary film, writing, publishing, Japan, and video art. DutchCulture had a conversation with her about her creative practices and the subject of self-identity.

You are finishing the programme of Directing Documentary at the Netherlands Film Academy right now. But you also have a bachelor's degree in History from John Cabot University in Rome, Italy. Tell us more about that.

“Both my parents are artists. Since I was little, the expectation was that I would also become an artist. But of course, as a teenager, you want to be everything but your parents. My romantic idea at that time was to become a historian in Rome. It was as if I needed to prove that somewhere else, I could be completely different. So I left Amsterdam at the age of 18.

Rome was a wonderful experience. I enrolled at the American John Cabot University where I met people from all over the world. I sort of created the study programme myself by choosing specific professors’ classes, with a focus on culinary history. I lived there for 5 years, and then I went to New York to study filmmaking for one semester. There I realised that I want to express history in a more visual way. Film is the medium to do so, specifically documentary.”

What does documentary making mean to you?

“It is a really useful, colourful and almost funky way to tell history. Studying history helps us understand ourselves and the world around us. But it can also feel abstract to dive into a past that has nothing to do with our present-day life directly. Filmmaking has the ability to capture the past in a way that you can immediately understand. When you film a historical narrative, you register both the past and the present with one image. It is something that I missed when I was only studying history.”

Why did you decide to focus on culinary history?

“We eat food every day, otherwise we would die. But the way you consume it, and your choice for this and not that type of food, create your identity day-by-day, I would say. Food is an attractive subject; probably because of its everydayness, and because many people love to eat. But the culture of eating has many different layers that are built up from the past, including the painful parts, of course - for example when it concerns animals as a source of human nutrition. I’m simply fascinated by everything around it.”

How is your experience at the Netherlands Film Academy? What kind of documentaries have you been making?

”After my New York experience, I returned to enrol in the Netherlands Film Academy, to properly school myself in all the aspects of documentary making. You know, the Netherlands has a rich history of documentary-making, Dutch people are really good at it. Here, perhaps this form of art combines reality and poetry in the best way.

At the Film Academy, I made a documentary titled De paling, de gabber en zijn zoon, to be released this autumn. It’s about eel-fishing in the north of the Netherlands, which is one of the oldest professions in the country but gradually disappearing due to environmental issues and overfishing. Nowadays there are only about a hundred fishermen left, still working in the way their ancestors did for hundreds of years. They are like cowboys of the sea, spending days on a boat just by themselves. Their strong understanding and poetic appreciation of the old craftsmanship are so beautiful. At the same time, the eel is an endangered fish, so its consumption is completely at odds with what I believe in. That’s the story and the complexity I want to tell with the camera.”

Speaking of which, does your Japanese heritage also shape your identity through food?

“My mother deliberately raised me in a Japanese way. In our house, there are always Japanese morals, rituals and ways of living. She made me return to my grandmother’s home in Japan every summer, which is by the sea in the mountains, quite far away from Tokyo. Japanese people communicate more directly through food than with words. So yes, I really understood my heritage through the food that my mother and grandma fed me. How they feel about the family, how they express love, and what they think is important. All are deeply ingrained in and reflected by their food. Maybe my relationship with food started from the way I primarily felt loved at home.

Dutch and Japanese cultures are very contrasting cultures. As a mixed child in the Netherlands, it’s quite complicated to be raised in a Japanese way. Everything I learned is the opposite of the things around me. It is challenging but also very charming because it gives me the energy to create my own self-identity, instead of having one made out for you already. Also, the Western world has a very specific perception of Japanese culture, and the way people here approach me or look at me reflects this perception. Even though I grew up here, just like them. I find that fascinating. Especially the eroticisation of Japanese women, which is something that is part of my everyday life, simply because of the way I look.”

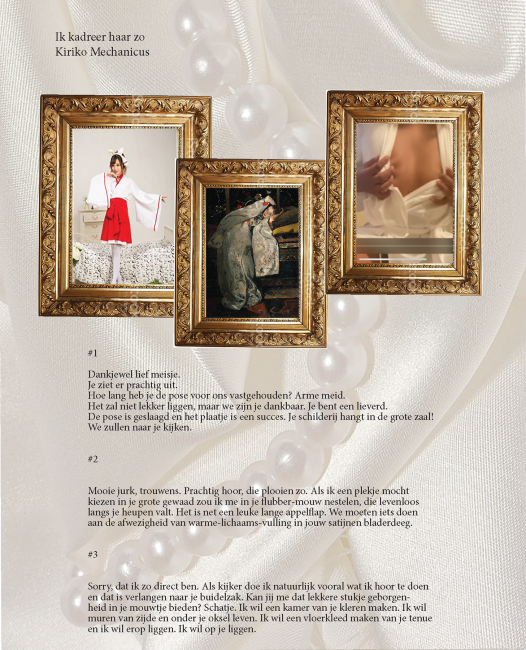

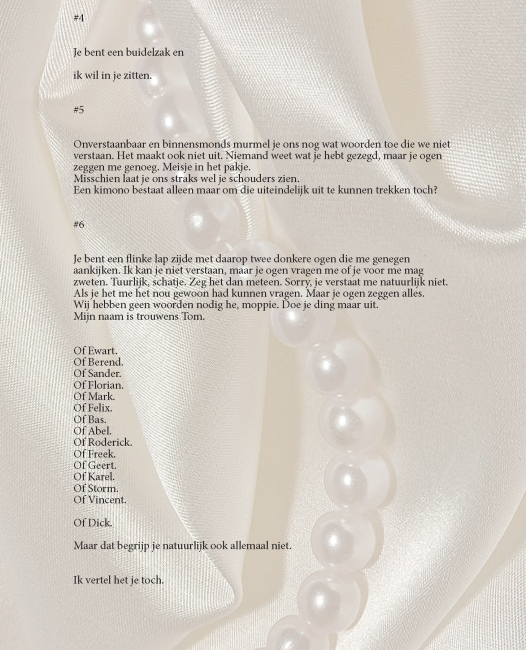

Does the poem Ik kadreer haar zo - that you wrote during the DeBuren writer’s residency in Paris last year - reflect your approach to the subject of identity and the gaze of others?

“Yes, I had to choose a 19th-century painting from the collection of Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and write a story inspired by it. So I picked the painting Girl in a White Kimono by George Hendrik Breitner (1894). Strangely, I started to identify with the image and think about how other people might perceive it. My story is about what it means to perceive, frame, deconstruct and persuade. It was presented on the Night of History at the Rijksmuseum along with my fellow residents’ contributions. Writing has been an ongoing practice for me. It started at Vice where I did an internship when I was 18. It was also the first time I wrote about food.

And I was very inspired by my friend, writer and journalist Pete Wu. His book and viewpoint really bear out how other (Dutch) people’s perception of East Asia can create your identity. Pete told me that his journey started when he went to the DeBuren writer’s residency programme. That’s how I applied for it as well. It was a wonderful experience that helped me to fully understand what I want to say and who I want to become. At DeBuren, I also started writing stories about bread and healing. I talked to many bakers and pastry makers in Paris. These stories are to be the first book published by the Jongenelis&Mechanicus publishing house that I set up with Una Jongenelis. She is a fashion designer but also makes comics, does performances and more – doing a lot of things, just like me.”

Any other future projects or plans?

“After the summer I’ll shoot my graduation work in Italy. It’s a 30-minute documentary film about the tomato. What I want to show is how tomatoes reflect people’s lives. Each tomato tastes differently to different people. For some they are sweet, but for others extremely bitter. For example, in the south of Italy, most tomatoes are picked by migrants from Africa who get entangled in a circuit of modern slavery instituted by the mafia. To them, tomatoes are anything but delicious. So it’s going to be quite a political film, about how the taste of food varies based on your heritage.

In the long run, I might make a documentary for the VPRO (a Dutch public broadcaster, ed.) about the fascination some people have for Japan. I feel much anger towards men with so-called yellow fever. Often my solution for things I hate is to try to learn to love them. So I thought I could make a film about dating these men, to deconstruct false fantasies about Asian women.”