The Russian invasion of Ukraine aims to destroy and deny the independent Ukrainian cultural identity, history, language, and heritage in all its forms. It can rightfully be called a cultural genocide. Therefore, it is crucial to support the Ukrainian cultural sector. In this context, DutchCulture is organizing an international visitors programme for cultural policymakers from Ukraine from September 25th to 29th, including representatives from the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture, the Ukrainian Institute, and the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation. For his occasion, author Jaap Scholten has written a personal story about the role and importance of art in times of war.

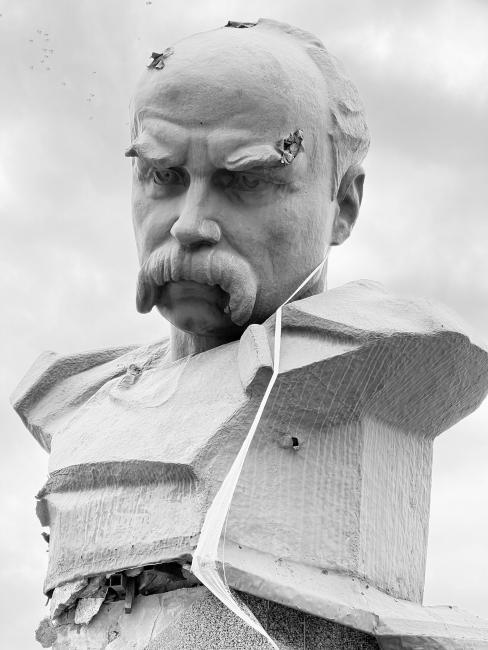

Three shell fragments have passed through the head of poet Taras Shevchenko on the central square in Borodianka. One fragment has come out through his bald forehead, another has made a hole the size of a florin beside his fontanel. Where they exited, the black metal of which the bust of the Ukrainian father of the nation is made, is bent outwards. The tiles, that covered the three-metre-high pedestal, now hang from wires or lie broken on the ground. Elsewhere in the city stands a damaged sculpture of the archangel Michael. At the playground on the corner, under the trees, is a life-sized, yellow-painted lion, beheaded by a shell.

Borodianka lies sixty kilometres to the north-west of Kyiv. The town has been reduced to rubble, its residents tortured and its heritage destroyed, including the local historical museum. Collapsed blocks of flats surround the bust of Taras Shevchenko. I wandered through the apartments. The doors and windows had been blown out of the buildings, every cupboard pulled open. I trod carefully, fearful of anti-personnel mines or tripwires, between the slashed cushions, clothes, excrement, curtains, children’s toys, pill boxes, packaging and little paintings of the people who lived there. Against the turquoise wall in the stairwell, in a sea of shattered glass, leaned a book with a picture of the Orthodox Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow on the cover – the abandoned souvenir of a plundering Russian, probably too heavy, I thought to myself.

No right to exist

“One of the justifications given for this war is that Ukrainians don’t have a distinct cultural identity," Alexandra Xanthaki, UN rapporteur for cultural rights, told The New York Times. Every day, Russian state media call for the total destruction of Ukraine. Putin has described the belief that Ukraine is a nation as a fiction.

“They are of the opinion that Ukrainians have no right to exist. This is the moment Russian imperialism has set itself to get rid of Ukrainians once and for all," said philosopher and essayist Volodomyr Yermelenko the day after I visited Borodianka. “What is wealth for you Europeans? As Marx put it: owning the means of production. Russians realize they can’t compete with the Western world when it comes to production, but they can compete in the field of destruction. They therefore want to own the means of destruction. The message they’re sending to us, to you, is that you can have control over the lives of people: but we control the deaths of people, we will decide at what moment you are going to die."

Men are being murdered, women raped, children abducted, and at the same time every trace of Ukrainian culture and history must be wiped out. Which is why the literature museum in Odesa, with the fragile spectacles of writer Isaac Babel in a glass case, is being laid waste, the museum in Okhtyrka with its centuries-old literary collection destroyed, the theatre sheltering hundreds of people in Mariupol bombed, the Sviatohirsk Monastery, one of the holiest sites of the Orthodox Church, severely damaged and even the Transfiguration Cathedral in Odesa hit by shelling. In Irpin, Bucha and Chernihiv I saw ravaged orthodox churches. In Chernihiv we stood in front of the town’s theatre, four weeks before it was hit by a missile. In Lukashivka we visited the ruined church; it had a huge hole in the middle of the roof, scorched walls, and a floor scattered with shredded paraphernalia. You can only stand and stare at it silently and shake your head.

One year after the invasion, Christianity Today registered 494 damaged or destroyed churches, monasteries and other religious buildings in Ukraine. Recently UNESCO, after an initial, provisional stocktake, reported that 27 museums, 105 historic buildings, 19 monuments, 120 religious sites, 13 libraries and an archive have been damaged or destroyed. The Ukrainian Ministry of Culture published a more comprehensive list of 1605 buildings of cultural importance that have been damaged or destroyed by Russian violence: 607 libraries, 90 museums and galleries, 28 theatres and concert halls, 120 art colleges and 760 creative hubs. UNICEF reported that 1,300 schools in Ukraine have been blown to pieces.

The figures change daily, because Russia is steadily destroying everything that is Ukrainian: schools, libraries, museums, theatres, hospitals. The Ukraine Crisis Media Center writes that 1,106 hospitals and medical institutes have been damaged, of which 174 hospitals are beyond repair. As it did in Syria, when firing at civilian targets in Ukraine, Russia often uses the 'double tap’ method: after an attack, a second missile is aimed at the same spot in order to kill as many rescue workers as possible.

The role of art in war

A year ago, I travelled to Ukraine with researcher and architect Ravenna Westerhout to make a documentary about the role of art in times of war. Ravenna had earlier studied the role that art played during the siege of Sarajevo in the Yugoslav war, a siege that lasted three and a half years. In Ukraine we interviewed writers, philosophers, painters, architects, musicians, visual artists and curators, asking them how they reacted to the war. Without exception they had all been paralyzed for the first few weeks, incapable of creating art. A few, mainly artists from active war zones, from Donbas and Mariupol, were often still incapable of doing any work other than as a kind of self-therapy. Some artists chose the most direct action; they took up weapons, left for the front and gave their lives.

Philosopher Volodymyr Yermelenko regards combatting propaganda as one of his principal tasks. “We should understand that the goal of critical thinking is always to get at the truth. The goal of Russian propaganda is to make you doubt everything. In the case of Ukraine, the key narrative was of course: Look, Ukrainians are horrible nazis and extremely cruel people. If you study history in any depth, you’ll see that the Russians were making this claim about the Ukrainians back in the 19th century, and if you read some Russian literary classics, it’s clear that the Ukrainian Cossacks, the warrior class of the baroque era, were generally depicted as bloodthirsty, violent people. So, they want to forget their history and erase every memory of them. Why would they do that? Because, to justify their cruelties against the Ukrainians, the Georgians, the Chechens, against other nations, they need to prove that those people are themselves cruel. In order to unleash genocide, you need to say that it’s genocide against people who commit genocide. To justify killing, you need to persuade everybody that only monsters are being killed. I think that the Russians, by dehumanizing Ukrainians, by saying all Ukrainians are nazis or something of the sort, by spreading these horrible lies, were putting in place a moral justification for the war. They were preparing their own citizens to think that it’s okay to kill Ukrainians because they’re all nazis. They were preparing Europe to accept it in some sense. I think these arguments are more effective with their own citizens, but they’re a good deal less successful among European citizens."

Yermelenko believes that artists must continue with their work as far as they can. “The war is horrible, the war is repugnant, absurd, but at the same time, it opens up an abyss, an existential abyss from which you can see many things in an entirely new way, as a philosopher, as a writer, as a painter. I urge all the creative people in Ukraine to carry on with their creativity."

Saying the unsayable

In his On the Natural History of Destruction, W.G. Sebald writes about the devastating bombing of German cities during the Second World War. Those few witnesses who spoke about it expressed themselves in vacuous language: “That fateful night when our beautiful city was razed to the ground." With a single exception, the scarce literature that Sebald found about those massive bombardments had nothing clear to say about the reality of the destruction. Putting into words or expressing in an image that which is unsayable is one of the possible tasks that fall to the artist.

"If you want real art, then it needs to represent real life, not just to be decoration. That’s not interesting, not now, not any longer," says Volodymyr Kadygrob, curator and advisor for the President of the Kyiv School of Economics: "The worst thing that culture can do is to cover up real life. The Russians have misused culture – their writers, their composers, their orchestras, their ballet – to give the impression that they’re a country like any other in Europe, a land of lofty ideals that it’s fine to consult with. The basic need now in the war is for documenting, documenting, documenting."

Vlad Sharapa, multimedia artist, says: “No, I don’t think that now, during the war, it’s the time to create art, not for me. I know exactly what I want, which is to help people or to participate in the defence of the country." With the volunteer organization Livyj Bereh (Left Bank), Vlad repairs the roofs of bombed houses and collects money by staging happenings and by auctioning rocket and shell casings to help the army buy footwear, clothing, night sights and all-terrain vehicles. Along the way, he documents the war and makes a collection of lights from destroyed tanks and armoured personnel carriers.

We accompany Vlad to a column of burned-out Russian tanks in the neighbourhood of Irpin. They stand next to the road, at the edge of the forest, rusted red-brown. Underwear, razor blades, vodka bottles, boots, toothbrushes and the lower and upper jaws of Russian soldiers lie scattered between the young Scots pines. Painted above the wheels of one tank is a blue bird with yellow wings, on the gun turret of another tank a yellow-and-blue butterfly. Vlad removes the lights from the T-72 tanks and notes the location, date and type of vehicle.

“I do this to record these places geographically," he explains. “Maybe it’s important only for me. I’m doing this so I can remember, you understand? Everything is starting to look the same now, in the Kyiv region, in the Kharkiv region, Chernihiv, it all merges. For me, putting together an archive like this is important." After the war, Vlad wants to use the lights to make an artwork.

Memory of lives cut short

When I come upon Vlad again a year later, in July 2023, he has signed up for the Ukrainian volunteer army. He will continually switch between two weeks of voluntary work and two weeks of army service. As well as preparing for the Vienna Biennale. With Livyj Bereh they have built a Theater of Hopes and Expectations. Vlad is also involved with the collective What Cannot Be Lost, which is made up of artists, sociologists, architects and researchers. “We’re building an intangible archive from fragments of the past. We’ve started by collecting memories of the lives that were cut short by the Russian air strike on the theatre in Mariupol."

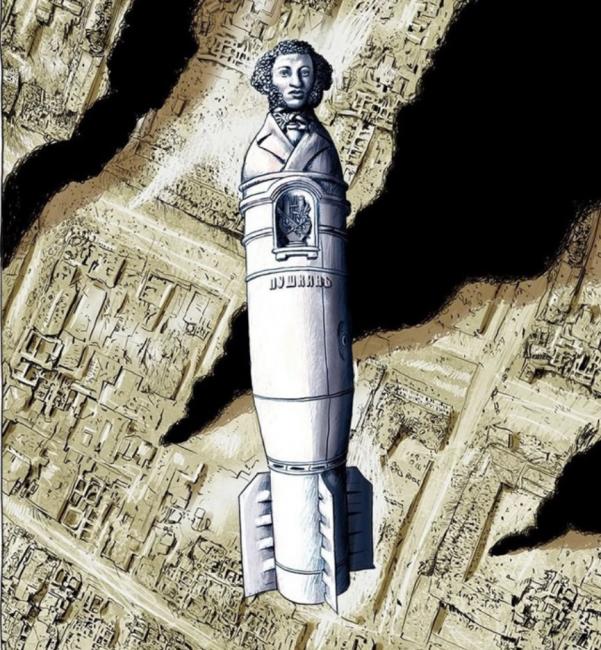

Ravenna and I drive through a capital city and across a country where all the statues have been wrapped in sandbags and sheets of wood or metal against Russian attacks. It’s another role of art: to protect the country’s heritage. All the statues are wrapped except those of Russian revolutionaries, military commanders and Pushkin. We see unprotected busts of the poet with the wild side-whiskers in towns he never visited. For many Ukrainians, the statues of the generals and Pushkin are now nothing more than a sign of oppression by the Russian colonizers. Russia dominated Ukraine for centuries and downgraded it to the status of a foolish provincial little brother. Russian propaganda was so dominant and effective that we in the West swallowed the Russian narrative whole, or at least in part.

Art plays an essential role in countering propaganda, exposing lies, accurately recording reality, giving hope, combatting trauma, offering people distraction and keeping them mentally healthy. During the Second World War, Elias Canetti noted that the task of the writer was to set things down precisely and responsibly. “If there were any point in thinking about what kind of literature is indispensable in our time, indispensable for a person who knows and who sees, then it’s this."

In On the Natural History of Destruction, W.G. Sebald writes, “On the other hand, keeping up everyday routines regardless of disaster, from the baking of a cake to put on the coffee table to the observance of more elevated cultural rituals, is a tried and trusted method of preserving what is thought of as healthy human reason."

In times of crisis, it becomes clear how indispensable art is. It defines who we are and helps us to remain human. In the case of Ukraine, every creative expression – whether a cake, a mural or a symphony – is a middle finger jabbed at the Russians. A middle finger that says the Ukrainians will never give up, and that their resourceful and often witty creativity will triumph over brutal, unimaginative Russian destruction.

Do you want to know more about this programme or about working with Ukraine? Please contact our Advisor Central and Eastern Europe Tijana Stepanovic.