The Dutch Trading Post Heritage Network (DTPHN) unites former Dutch East Indian Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) trading posts throughout Asia. This first meeting in the Netherlands was attended by member organizations from Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and Japan. The network is a living testimony to the intertwined nature of global historical relations. The network is a collaboration between institutions that care for the heritage of VOC trading posts in different parts of Asia. Some are existing forts, while others are working through archaeological excavations to dig up the shared past.

During the DTPHN symposium that we organised in December, they presented their stories and challenges in the Dutch heritage field. The symposium was introduced by Remco Vrolijk, International Projects Coordinator at the Hirado Dutch Trading Post in Japan and secretary of the DTPHN since its founding in 2015. Vrolijk explained that the need for a network uniting the different sites of VOC heritage in Asia was born out of a common need to share knowledge, stimulate exchange, and increase awareness of the heritage of the VOC in Asia. In 2011, the Hirado trading post had been restored and after its festive opening, they felt a need for exchange beyond the Japanese context. The main histories that are told at the Hirado trading post are about interregional trade, but at the time they had no idea what was being done to understand and preserve related heritage sites in other Asian countries such as Thailand and Taiwan.

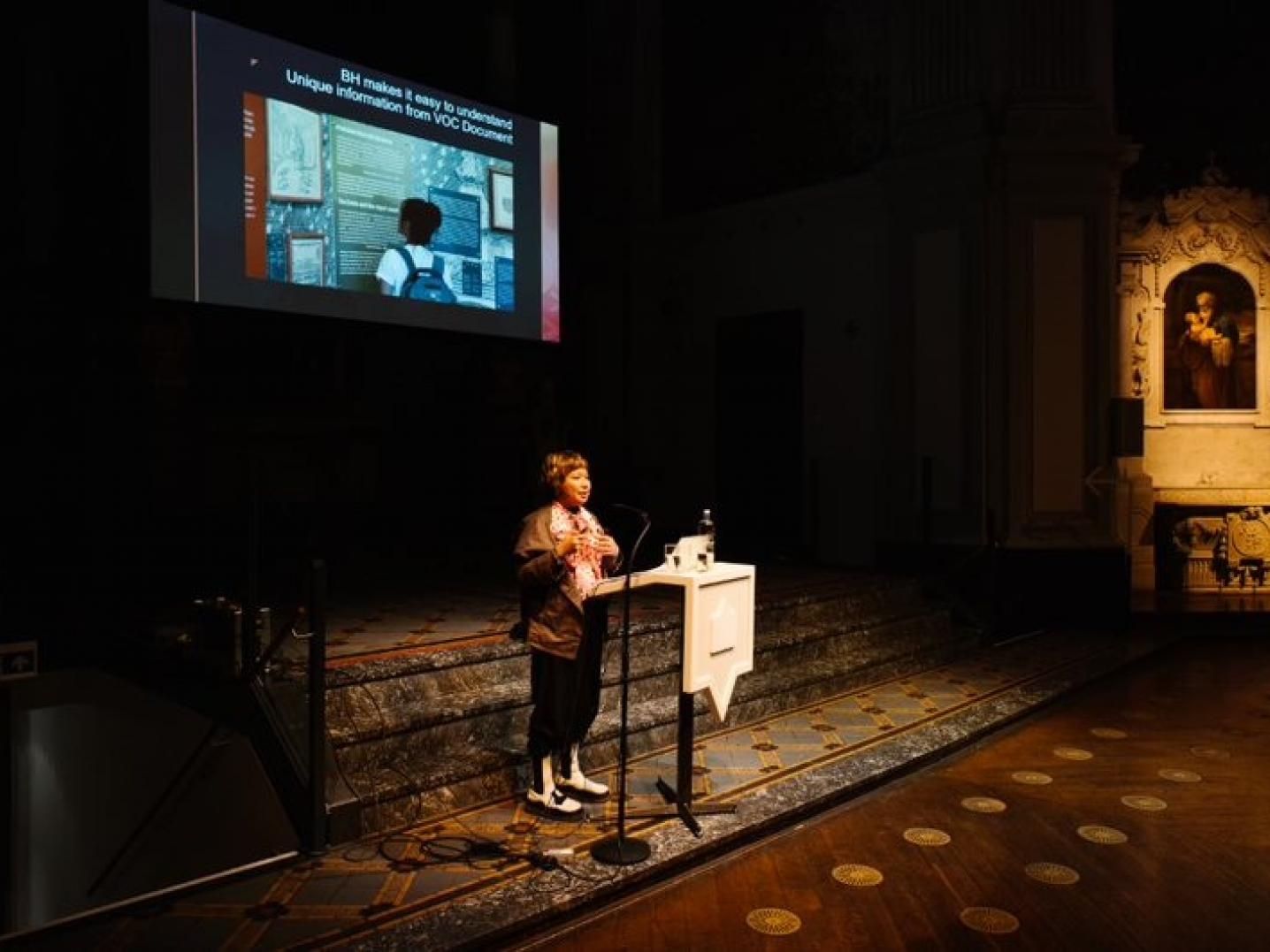

The network was founded specifically to unite an interdisciplinary group of historians, curators, architects and urban planners. The scope of this initiative is not limited to specific disciplines, as the restoration and adaptive reuse of the former VOC sites would benefit from a wide range of heritage expertise. The members of the network are heritage organizations, which are represented by different participants present at the symposium on 8 December. De Duif was purposefully chosen as a location for this symposium. As a church-turned-event-venue located at the Prinsengracht, it is an example of a successfully renovated monument following the principles of adaptive reuse, much like the heritage sites that are part of the network. Paul Morel, project leader at Stadsherstel Amsterdam, gave a short introduction to the adaptive reuse of De Duif and other monuments. Stadsherstel buys and restores derelict monuments, such as houses, churches or industrial buildings, in Amsterdam and its surroundings, and then rents them out. This model has been so successful that it has been adopted in Paramaribo, Suriname and Stone Town in Zanzibar, Tanzania. The Stadsherstel approach to restoration, reuse and management is similar to those of the members of the network.

The Fort Oranje of Ternate

The first speaker to take us to one of the DTPHN sites is Maulana Ibrahim. Ibrahim, an architect by training, is the founder of the organisation managing Fort Oranje on the island of Ternate, part of the Maluku Islands of Indonesia. The history of Fort Oranje is a specific case, as Ibrahim explains, as in Ternate the VOC was invited by the Sultan to defeat the Spanish navy. This part of Indonesia’s history is mostly omitted from the historical canon. The relationship between the VOC and the people of Ternate cannot simply be read in terms of colonial-imperial, as Ibrahim explains. He does not mean to counter the general interpretation and understanding in which this history of overseas European trade is generally understood, but the case of Fort Ternate shows this global history from this local perspective. Fort Oranje is an interesting heritage site as it tells this story, and it is exactly the place to learn about this part of Indonesia's history.

At the historical site of Fort Oranje, there is also a strict policy in place to maintain its character as a public space, loved and used by the local community. The restoration and management of the site is funded by the Indonesian government, and the interior of the fort is adapted into a multifunctional community space. The fort includes rooms to host workshops, a co-working space, and an exhibition room, while the entire complex is the site of an annual heritage festival. Ibrahim points out that the fort is in the middle of the city, and since the activities it hosts are generally free to the public and well attended, the site's redevelopment is generally considered a success.

Although the fort is a cultural hub and a local success, it is a struggle for Ibrahim and his team to fulfill its touristic potential since it is out of the way from the popular destinations on Java, Bali and Sumatra. Another challenge they face is how to continue running the fort in a more sustainable way. Ibrahim is open to working with partners to develop a new long-term strategy for the Fort Oranje heritage site.

Dutch Trading Posts in Taiwan

The next speaker is Professor Ping-Hsiang Hsu from Tainan, Taiwan. He takes us on a tour around the landscape of Dutch fortifications in Taiwan. The Dutch colonized the Tainan area in southern Taiwan from 1624 to 1662, and during this 38-year period, many fortifications were built. Professor Hsu explains that since this is a relatively short period, dating more than 350 years back, not many material artefacts are left that can be used to tell the stories of this period. An example Professor Hsu mentions is Fort Zeelandia, which was partly destroyed by an earthquake in the 19th century. Professor Hsu is currently mostly conducting research into the feasibility of this fort's reconstruction, and the implications of such a project to its ‘authenticity’ as a heritage site.

Professor Hsu continues to address questions that are central to the discipline of heritage conservation. If one restores a heritage site, which period should it be restored back to? The VOC fortifications did not only serve the Dutch colonizers, but also held strategic positions to many military regimes that followed. Another question is whether these heritage remains could also be reconstructed on a different location: due to local concerns and climatological reasons, it could be more feasible to rebuild the fortifications at a different location than the original one.

The possible reconstruction of the VOC fort requires extensive historical and archeological research. While there are examples of other VOC heritage sites outside of Taiwan that have been able to get funding from the Dutch government and international funding bodies, Taiwan’s geopolitical situation and the tensions with China make it difficult to gain access to these funds. There are examples of discoveries outside of Taiwan that have shed new light on the Dutch colonial period in Taiwan: Professor Hsu mentions how the 1643 Estate Registers of Fort Zeelandia were recently found in a Dutch archive in Amsterdam.

Hirado Trading Post in Japan

The reconstruction of the Hirado trading post in Japan was the project that prompted the foundation of the DTPH network. Initiated in 1978, it was finalized in 2011. Much like Tainan, in Hirado the VOC site had to be reconstructed through archeological research. To make way for the reconstruction, people living in the area had to be bought out. To ensure local people supported the project, the coordinators of the project continuedly organized seminars and community meetings, which eventually ensured large local support. The reconstruction of Hirado trading post gave an impulse to different kinds of cultural activities in the region, as the new building consisted of exhibition and workshop rooms that could be used for a variety of purposes.

Dutch-Japanese relations are integral to the programming of the Hirado trading post. The first exhibition organized on the site addressed LGBTQ pride, a topic in which the Netherlands can be considered a forerunner, according to Hirado curator Yohei Ideguchi. He explains it had been difficult to make this exhibition in a public museum in Japan, but it was successful because of the development of a public-private partnership. Apart from exhibitions, the reconstructed site supports several intangible heritage initiatives. An example is different food workshops it has organized, using recipes and ingredients that were typical of the 17th century, such as the spices that became available through the interregional trade routes. Working with intangible heritage is something most of the heritage sites of the network are specialized in, and as such can be inspirational to Dutch heritage professionals.

Baan Hollanda of Ayutthaya in Thailand by Raveedaon Estrella Montien

As a last stop among the VOC trading posts, we hear museum consultant Raveedaon Estrella Montien speak about the Baan Hollanda heritage project in Ayutthaya in Thailand. Baan Hollanda is a museum that was built in a style that was inspired by Dutch colonial architecture. The central question of its exhibitions is: ‘What were the Dutch doing in Ayutthaya?’ As the Dutch historical relation to Thailand is a relatively unknown part of history, in both Thailand and the Netherlands, the site managers had to start from zero in addressing their audiences. Although Baan Hollanda is currently closed for redevelopment, Montien takes us through her current project of creating a digital visitor experience, which is a collaboration with the Dutch design agency Fabrique. This experience translates the museum’s physical collections into a digital environment and tells the story of the Dutch-Thai historical relations. The Baan Hollanda Museum aims for a successful integration of this digital environment with its physical exhibition spaces. Digitisation provides new opportunities for sharing knowledge within the network. The hope is that when Baan Hollanda achieves its digitization project, other members can join and learn from their experiences.

Advice for the Dutch Heritage Sector

The different presentations of the network members show that for a heritage site, whether the Hirado trading post in Japan or Fort Oranje in Ternate, its current social function is imperative. The different disciplines of the network members shed light on the importance of an interdisciplinary approach towards the presentation of VOC heritage. In a concluding remark, moderator Alicia Schrikker emphasizes that particularly the approaches by the different members of the network towards intangible heritage are of interest to Dutch heritage professionals.

The network members indeed noticed during their stay in the Netherlands that here there is more material-focused approach to heritage conservation. This approach could still benefit from including the intangible aspects of heritage, and seeing it more as a living practice. It is the network’s heartfelt advice to Dutch heritage professionals to pay attention to the social and cultural context in which physical objects were created and used. By working with heritage professionals from Asia, and listening to the local histories, we can get new and more inclusive insights into our own colonial history.