While we are familiar with the concept of hospitality, what does it truly mean within the arts and cultural workplace? What forms of hospitality can we envision for a future that seems to have arrived yesterday?

Hospitality is at the heart of residence programmes that offer artists and other creatives the opportunity to work elsewhere. Welcoming artists in a new place, encountering other perspectives and communities, and helping them to focus on the next step in their practice. From an independent artist-run programme to an institutional career stepping stone, for many, they serve as places of refuge, learning, reflection, and regeneration. Besides being creative catalysts, some programmes are specifically dedicated to offering a safe haven for artists and creatives fleeing from crisis or conflict.

Over the past decade, the number of such programmes has increased significantly, peaking after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. In response, numerous residences, cultural institutions, municipalities and art professionals joined existing networks like Artists at Risk to offer displaced artists an ad hoc first line of support. New regional residency networks emerged to address the catastrophic situation in Ukraine, such as the SWAN (Swedish Artist Residency Network), which connects Ukrainian artists with Swedish residencies offering short and long stays for individuals and families. Individual cases also highlight this effort; for instance, Co-iki micro-residency in Tokyo adapted their programme when they learned their guest artist could not return home. They provided housing and guidance to build a future in Japan, while continuing an online residency to support another artist in Ukraine. Many residency programmes, along with art institutions, theatres and festivals, have shifted their focus toward addressing the tragedy of war and fostering solidarity and resistance.

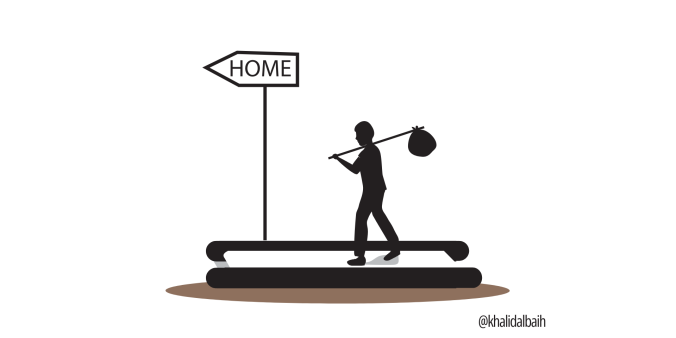

As we confront this new reality of forced migration due to war, persecution or crisis, a question arises: how can the cultural field be permanently open to professionals who are forced to relocate, regardless of their country of origin?

Hosting, learning, changing

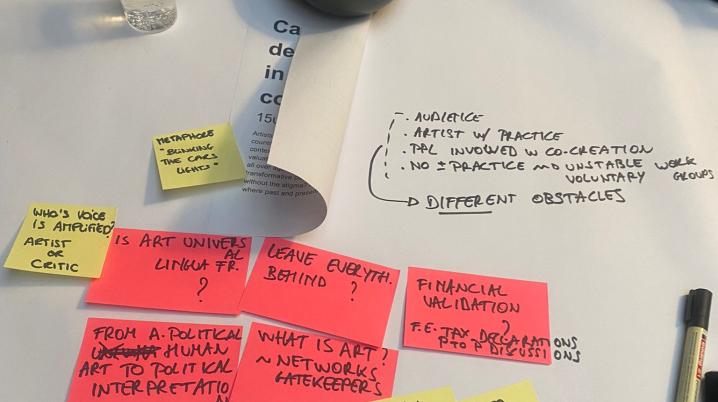

To explore this question further, TransArtists collaborated with Kunstenpunt in Belgium to organise a peer-to-peer meeting in February 2023 at Globe Aroma in Brussels and a symposium few months later at Brakke Grond in Amsterdam. This gathering brought together professionals from the cultural and humanitarian sectors across Flanders and The Netherlands. The programme in Brussels included working sessions on subjects ranging from protocols for initial crisis response to the interactions between policy makers, refugee workers and art communities. Sharing firsthand experiences among colleagues from the art scene, social workers, and displaced artists proved invaluable. Reflecting together on how to improve current structures and policies allowed to decompress as many of the participants were grappling with reworking their programmes, securing funding, or finding locations to house displaced families while assisting them with trauma relief.

Discussing strategies to enhance access to various circuits within the Western European professional art scene revealed systemic concerns. Cultural worker Milica Ilic, also present that day, noted in her article, Hosting Learning Changing:

Extending this argument, the significance of informal and professional cross-border networks among artists and organisations, and cultural policies supporting this, cannot be underestimated. Marjolein van Bommel, financial director at Toneelmakerij, expressed her appreciation for the European Theatre Convention (ETC): “Shortly after the invasion in February 2022, it took one phone call to our colleagues in Kyiv to establish a collaboration and a residency in our theatre's attic in Amsterdam.”

As we know, first crisis response is essential, and there has been a lot of support; but what happens three years down the line? As we’ve seen after other wars and crises, in time the attention wanes. This was also a concern during the meeting in Brussels. Shouldn’t we involve newcomers, their perspectives and experiences in the decision-making processes of institutions and governments, hence learning and building on each other’s competencies?

Tools for change

To enhance accessibility for and to stimulate the engagement of newcomers within cultural organisations, David 'Ramos' Joao, artistic leader of Fameus, developed the "Stop-up Plan": a toolkit based on their experiences with assisting newcomers in Antwerp. Similarly, Judith Depaule from Atelier des Artistes en Exil in Marseille presented their collective platform "Exile Lab," which supports approximately 500 artists in exile across Europe through, amongst other things, an online portfolio database and connections to galleries and art venues.

Bright Richards, theatre director and once a refugee himself, connects refugees with potential employers through storytelling because “the connections made in a new country significantly shape one's trajectory.” He encourages theatres to collaborate with partners outside the art sector, such as local governments, humanitarian organisations and commercial parties to achieve common goals.

Regarding the pitfalls of tokenism, and preconceived notions of diversity within art institutions, artist Thais Di Marco comments that “we might need a more democratic approach to subjects such as diversity to dismantle the power dynamics within the visual art sector.” A fair point. How can cultural organisations become more open to otherness? Josien Pieterse, director of Framer Framed in Amsterdam, spoke about their effort to transform and gradually integrate the community aspect from within. Initially established as a nomadic platform critiquing colonial history presentations in Dutch museums—and exploring alternative artistic practices—they have since transitioned into curating exhibitions that spark conversations about curatorial choices. In 2016 they opened a community hub in the north of Amsterdam that allows them to host events while facilitating educational programmes and social practice residencies. During the pandemic-induced shutdowns, the organisation embraced new approaches with local groups, such as those focused on cultural psychiatry and refugee experiences.

Superpower

A contrasting perspective emerged when DutchCulture | TransArtists hosted five residency organisers from various regions in Ukraine from November 25-29 as part of a visitor programme to connect and exchange with colleagues in the Netherlands. They receive displaced artists, facilitate care for the local community, and present exhibitions and events reflecting everyday reality despite the threats from rockets overhead, power cuts and limited resources. “We operate within the curious combination of tragedy and invention”, said Bozhena Pelenska, director of Jam Factory Art Center in Lviv, during a public talk in Amsterdam. “It is indeed our superpower,” added Alona Karavai, director at Asortymentna Kimnata in Ivano-Frankivsk: “Our vast networks in and outside the art scene are rooted in shared values that date back to different waves of activism since Ukraine declared its independence in 1991. There is huge trust and solidarity with each other that we can fall back upon.”

Fostering hospitality within the arts—with the aim of creating a more inclusive, diverse and supportive community—requires a two-folded approach. On the one hand we need micro-level solutions; on the other, we must recognise and bolster the myriad grassroots art initiatives that each confront systemic injustices in their own unique ways. Our meetings with various organisations and workers reveal that small-scale alternative systems, networks, groups and communities are already in place. The evolution of these interconnected residency and cultural networks, both private and professional, highlights their immense potential, particularly during times of crisis. To harness this potential, it is crucial to keep connecting them. Through hosting, learning and adapting, we continue to progress towards integrating their impact across borders, sectors, and disciplines.

Natalia Ivanova, director of CAC Yermilov Centre and founder of residency Art Kuzemyn, located in a bunker in Kharkiv, stated in her presentation at De Balie: “We do not have to make a choice whether to work or not. We have a space where we can create, show, present, and meet - so we have to do it. We can help artists and partner institutions– so we do! We can arrange discussions, events, debates on decolonialisation, derussification and many other vital issues – so let’s do it! Because everything we do today will affect our future.”