Ginna Brock on Cosmopolitanism in the Arts

What does it mean to work internationally as an artist anno 2020? Are the traditional categories, such as ‘international’ and ‘cosmopolitan’, still sufficient to both describe the ambitions of artists and cultural workers, and address the challenges of working in a globalised world? In order to reflect on the conditions and effects of cultural collaboration, DutchCulture explores in a series of colloquia relevant new research in the field of cultural internationalisation.

On June 24, DutchCulture organised the second in this series, a colloquium on cosmopolitanism in the arts, during which dr. Ginna Brock (University of the Sunshine Coast) gave the following keynote speech on how contemporary cosmopolitanism relates to Ancient Greek notions of hestia, xenia, and the polis.

Non-Linear Belonging as a Creative Companion to Cosmopolitan Realisation

Hello everyone. It is a privilege to be here (virtually) with you and to open discussion on new ways of seeing and applying ideas of transnationalism and cosmopolitanism. Two quite loaded terms that both have the ideas of the national and the citizen at the core. The paper that I will be drawing from today was a contribution I made to the edited book entitled Beyond Cosmopolitanism. My contribution was titled ‘Cosmopolitanism Beyond the Polis: Creative Memory Works and Reimaging the Relationship between Hestia and Xenia’. The impetus behind this submission came from my doctorate investigation into the representation of the family in Ancient Greek Tragedy and it was through my analysis of the extant plays that I located the unassuming presence of the hearth, or as the ancient Greeks called it, Hestia. My research quickly shifted to uncovering all I could about this common object that was deified into the goddess, Hestia (one of the original 12 Olympians) and the importance of hestia to the Ancient Greek. Ultimately, I concluded that Ancient Greek tragedies out forth the idea that ‘to be is to belong’. Since my completion of the PhD, I have been asked to contribute more broadly on my understanding of Belonging – going into the socio-political, economic, and even the social media sphere.

Today, though, we are going to focus on some of the problematic elements surrounding notions of cosmopolitanism and look specifically at some of the underlying benefits of moving away from ideas of citizenship to ideas of belonging.

To be is to dwell

Martin Heidegger proposes that to be human is ‘to dwell’ (1954 in Meagher 2008:121). Heidegger, here, is proposing an ontological concept of ‘dwelling’, one that transcends a physical location or dwelling place. For Heidegger the terms ‘dwelling’ referred to a ‘coming into a right relation’, While predominantly ontological in its articulation, this idea can also be seen as an ethical understanding of an individual’s relationship to others and to the earth: a means of being positioned ‘within’ a collective and, thus, a dual form of ‘belonging to’ and ‘belonging with’. In this way, ‘dwelling’ creates a profound tension: ‘to dwell’ is to both exist and co-exist. The tension between establishing self and reconciling responsibilities to others is at the heart of the cosmopolitan ideal. For how can an individual claim to be a citizen of the world―a member of the human race―without an understanding of how their own individual identity is, in fact, a composition of multiple levels of belonging? An individual’s sense of belonging is established through a synthesis of familial upbringing, community experiences, cultural traditions, ethnic expressions, and national demands. This is why the cosmopolitan impulse invariably raises ontological questions: Who am I beyond myself? Where do I belong? What informs my sense of being? How do I reconcile myself with other beings? What are my ethical and moral responsibilities to others? How is ‘other’ defined on a cosmic level? The answers to these questions can provoke a sense of unease, as they disrupt the conventional understanding of self as singular. Yet, the recognition of the multiplicity of being is crucial to cosmopolitanism.

Cosmopolitanism can be seen as an individual’s progression towards reconciling (not rejecting) a multiplicity of belonging. In order to articulate this concept, I have termed the understanding of multiple levels of belonging as a ‘hestian composition’. In Ancient Greece, the goddess Hestia, one of the original twelve Olympian gods, exemplified the ontological notion that ‘to be is to belong’ (Brock 2014). In the pursuit of the modern cosmopolitan ideal, it can be beneficial to examine past attempts of world citizenship. The focus on the pre-polis Ancient Greek concept of the goddess Hestia, and her realm of the hearth, provides a foundation for understanding the multiplicity of belonging. From this foundation, analysis of the only non-kin relationship formed at the hearth, the xenia bond, exposes the tenuous relationship between the security of self (existence) and the offering of hospitality to others (co-existence). The precariousness of the relationship between hestia and xenia raises a paradoxical question for our modern conception of cosmopolitanism: does the decentralisation of the hearth (a rejection of the multiplicity of belonging) perpetuate a xenophobic mentality?

Re-centring Hestia

From Diogenes of Sinope’s first utterance of ‘kosmopolitê’ (world citizen), the polis has been the focal point of the cosmopolitan impulse, positioning humans as predominantly citizens. Yet, before the construction of the polis, Ancient Greek society was organised around the ἑστία—the Greek word translated hestia, meaning hearth. The hearth―a common communal space within the Greek home―can be viewed as an external manifestation of the innate human impulse towards connectivity and belonging. The sacredness attached to the hearth is evident through its deification into the goddess which shares its name. In Greek antiquity, the goddess Hestia was positioned as the central point of all levels of connectivity; to the gods, to the earth, to the nation, to the city/state, and to the familial line. A hestia-centric mentality shifts the understanding of self as ‘a citizen of the world’ to a realisation of self as a member of the human family and promotes cooperation and compassion over competition and domination.

For the Ancient Greeks, the hearth was considered the sacred origin, and the pre-Socratic philosophers position the hearth, and thereby Hestia, as the centre of all being. For Philolaus, from the Pythagorean school of thought, the entire universe was Hestia-centric; the ten celestial bodies rotated around a central fire, which was Hestia (Songe-Moller 2003:14; Heidegger in McNeill & Davis (trans.) 1996:112). This hestia-centric positioning has two distinct ramifications. Firstly, the hearth, and therefore belonging and connectivity, is positioned at the centre of human existence. For the Ancient Greeks, the centre represented an honoured and sacred position. Their maps centralised Greece and located the oracle at Delphi as the exact centre of the world, and Hestia is said to have drawn her fire from the centre of the earth (Croally 2005:61). In this way, Hestia can be envisioned as the ‘world hearth’, around which all of humanity is anchored and called to gather. Secondly, the hearth not only situates a person physically, but also has ontological and psychological implications. Heidegger positions the hearth as the origin of being, suggesting that ‘the hearth is the enduring ground and determinative middle—the site of all sites, as it were, the homestead pure and simple, toward which everything presences alongside and together with everything else, and thus, first is’ (in McNeill & Davis (trans.)1996:105). The significance of this triadic positioning― the beginning of all existence, the incessant presence of all being, and the ultimate place of return― indicates a permanence of being that can never be severed: Hestia simply is. To begin with the hearth is to begin at the origin of all being and to acknowledge the human impulse to belong to the earth and to others. This acknowledgement, then, transcends a specific locality of the hearth and reveals an intrinsic impulse to belong to the world’s hearth.

For Seneca, both the world hearth and the more specific locality dictated through birth governed an individuals’ notion of belonging: "We must grasp that there are two public realms, two commonwealths. One is great and truly common to all, where gods as well as men are included, where we look not to this corner or that, but measure its bounds with the sun. The other is that in which we are enrolled by an accident of birth – I mean Athens or Carthage or some other city that belongs not to all men, but only a limited number. Some devote themselves at the same time to both commonwealths, the greater and the lesser, some only to the one or the other" (in Copper and Procopé (eds) 1995:175).

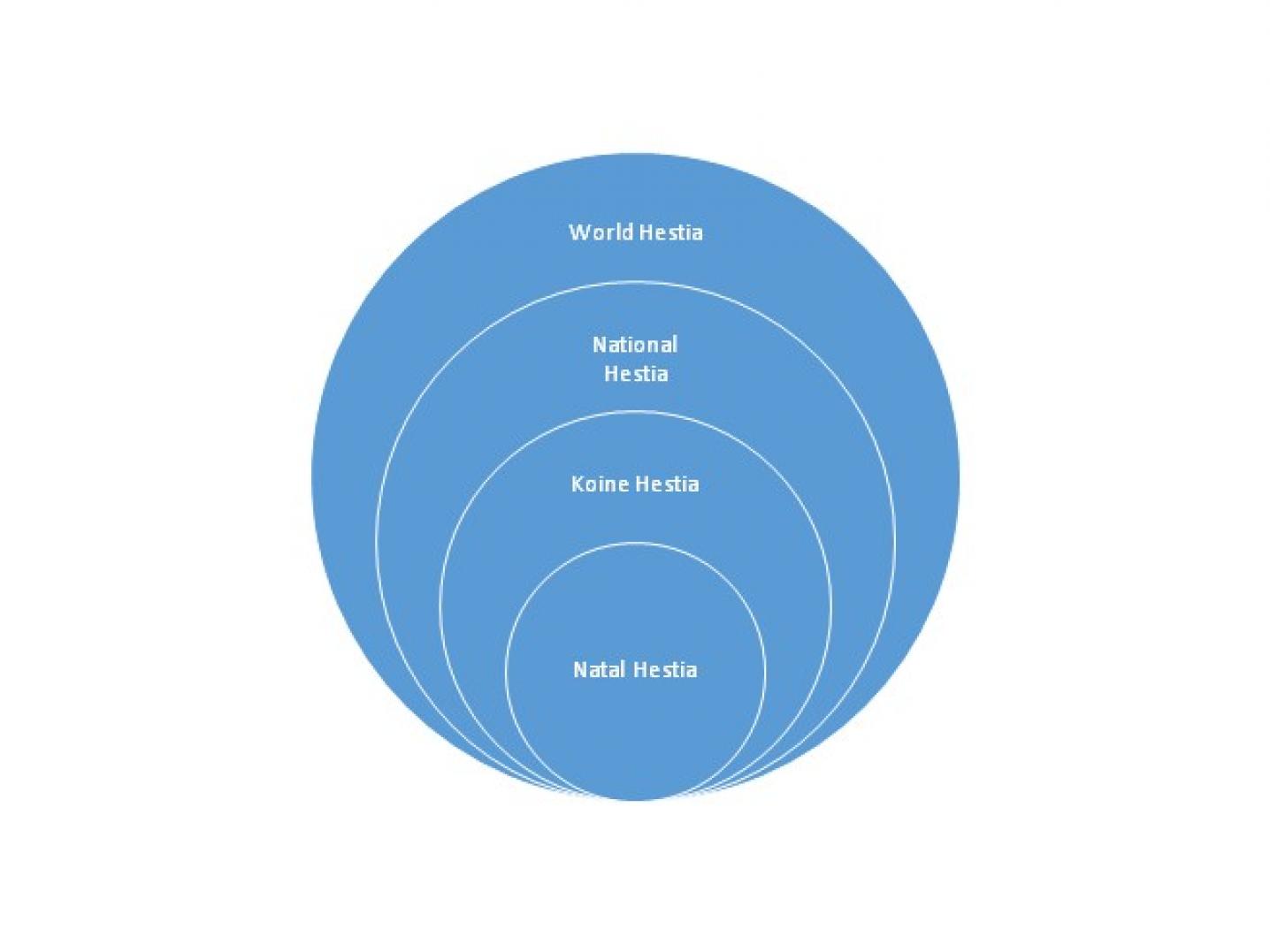

Even though Seneca conflates these two ‘commonwealths’, the world hearth is described with natural images, whereas the polis is described as an social institution in which individuals are ‘enrolled’. In this way, Seneca introduces the idea of ‘cosmic belonging’, a belonging to the world that is not dependent on political, cultural, social, or moral rules: it, like Hestia, simply is. Membership to the world hearth is established at birth. An individual is born into the species of ‘homo sapiens’, exhibiting a distinct humanness, and therefore permanently belongs to the human race. However, the ability to recognise the self (or others) as belonging to a world hearth is contingent on a person’s ability to reconcile the multiplicity of his/her individual configuration. The cosmopolitan impulse is not necessarily, as Kleingeld recognises, a human’s first psychological development: "It may well be the case, as many cosmopolitan theorist in fact assume, that our narrower loyalties develop before the broader ones do. Thus, as a matter of moral education, children may need to learn to broaden the scope of their affiliations from that of the family, to the local community, to the country, to the community of all human beings" (2012:37).

Kleingeld’s acknowledgement of these social levels, along with Martha Nussbaum (1994) concept of being as concentric circles of belonging, approach an understanding of an individual’s hestian composition. Yet, when the world hearth is viewed as ontologically first (not the individual as Nussbaum posits), a new understanding of connectivity and belonging emerges. The concept of the world hearth being ontologically first yet psychologically last to be realised situates cosmic belonging as an already established existence to which human beings strive to return.

Hestia, as the first and last, evokes two clear conceptualisations for cosmic belonging. Firstly, Hestia being both first and last forms a metaphoric circle and unifies participants around the hearth (Vernant 2006:173). In Greek society, the hearth formed a boundary of inclusion; everyone within the circumference of the hearth’s fire entered into a hestian identity, where the individual became part of the collective: "The two extremes of both time and space traced the closed circle of a sacrifice turned inward upon itself- a kind of virtual self-sacrificing designed to promote the growth of the virtue of centrality around a deity of fire who in herself exalted the identity of all those gathered to eat together, seated in a circle around her" (Detienne 2002:65).

Marcel Detienne proposes that ‘around the deity of fire’ (Hestia) the self is sacrificed and a hestian identity is formed. In this way, when Hestia is viewed as a world hearth, it can be reasoned that all beings attached to the earth should be protected within the circumference of the earth’s fire. Secondly, Hestia as both first and last, is indicative of an ever-present impulse to return to the origin (the world hearth). By providing a stable position, like the fixed point of the compass or a fulcrum, Hestia enables movement with the assurance of return. The world hearth, therefore, can be considered both omnipresent and all-inclusive. If Hestia is regarded as the world hearth and is both the first circle to which all human beings belong and an ever-present impulse of return, then the purpose of our existence is to re-discover cosmic belonging. Yet, some of our social structures aim not to unify, but to divide; not to celebrate difference, but to vilify the unfamiliar; not to show compassion and work in cooperation, but to compete and dominate.

In order to achieve an understanding of belonging to the world hearth, an individual must first traverse through narrower forms of belonging. The design of these more particular hestian constructs indicates our impulse toward cosmic belonging. Edward Edinger concludes: "It is not possible to worship at the hearth of the human family―that is the cosmopolitan whole―until one has first worshiped, and still worships, at the hearth of one’s more particular locality. For the larger and more comprehensive viewpoint to be authentic, it must be based on a solid relation to one’s particular origins; otherwise, cosmopolitanism can be nothing more than alienation" (1994: chapter 4).

Edinger raises three important conceptual ideas for realising cosmic belonging. First, the use of ‘still worships’ indicates that a person does not renounce one hestian unit in favour of another. In this way, cosmic belonging can be seen as a synthesising and enlarging of an individual’s unique hestian composition. Secondly, the use of the word ‘solid’ signifies the importance of hestian stability. An individual’s ability to transcend different hestian identities, as well as an individual’s openness to recognise and respect alternative hestian constructions, depends on the security of one’s own hestian composition. The use of ‘one’s own’ might seem antithetical, however recognition of one’s own is crucial to understanding cosmic belonging. The ability to recognise ‘one’s own’ in a more specific context enables recognition of the entire human race as one’s own. The third conceptual idea that Edinger raises is the notion that without an understanding of hestian composition, cosmopolitanism is a form of alienation or homelessness―a feeling of being disconnected from humanity. A thorough investigation of the Ancient Greek tragedies locates homelessness as the most tragic condition for humankind (Brock 2014), and the construction of physical dwellings and homesteads attests to the human need to create spaces that satisfy the need to belong.

For the Ancient Greek’s the domestic, or natal, hearth represented the original site of connectivity to the earth. Rooted in the ground, yet opened to the heavens, the domestic hearth served as the first attempt to emulate the world hearth on a microscopic level. The ‘evolution from fire-site to hearth-site’ established a permanent and chthonic connection, demarcating a settled, contained, and confined space (Vernant 2006:158; Thompson 1996:21). Simone Weil suggests ‘to be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognised need of the human soul’ (2002:43), and the placing of the hearth, along with its deification, exposes this psychological need for a ‘rooted’ sense of belonging. However, this ‘rootedness’ does not necessarily require a defined physical space. While the physical hearth provides a fixed and permanent centre that solidifies an individual’s sense of self, the psychological experience of home exists beyond the boundary of property lines. Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenological investigation in The Poetics of Space, analyses the ‘house’ as both a ‘real’ and an ‘imagined’ space that provides insight into the human psyche: "In the life of man, the house thrusts aside contingencies, its councils of continuity are unceasing. Without it, man would be a dispersed being. It maintains him through the storms of the heavens and through those of life. It is body and soul. It is the human being’s first world" (1994:7).

The position of the ‘home’ as an individual’s first ‘world’―a world which ‘maintains’ the individual through the storms of life―situates security and stability as a crucial element to an individual’s understanding of self. Bachelard suggests that the ‘unhoused’ individual is a ‘dispersed being’. The connotation of ‘dispersed’ generates notions, proposed by Edinger above, of separation and alienation, where the scattered individual is no longer ‘whole’. Therefore, to be separated from the hestia (whether from the world hearth or a more particular hearth) is equivalent to dismemberment; to be without home, without chthonic roots, without belonging to others, is to be without the fullness of being. The domestic hearth is the first hestian cornerstone and is foundational to the very composition of an individual’s sense of self and this initial understanding of self remains with the individual even as they venture forth from the familial into wider spheres of belonging.

From Hestia-centric to Polis-Centric

The creation of the polis was originally designed as an additional layer of human interaction and belonging; a coming together of a group of people dedicated to improving their current living conditions. The vital elements in the construction of the polis are that ‘citizenship implies belonging, being an insider’ (Goldhill 1986:58) and that the polis creates a ‘human community’ (Rehm 2002: vi). Using the hestia-centric model from the domestic sphere, the polis organised approved households around a koine-hestia, or communal hearth. Indeed, the creation of the koine-hestia elevated the concept of the polis to a ‘household of households’, adopting many of the aspects associated with the hearth (Croally 2007:165). Therefore, the polis, as a means to create a shared existence, was an expansion of an already established hestia-centric mentality. The Ancient Greek polis established culture, reinforced ethnicity with like-minded individuals, provided more specific and particular solidarities that served to organise human life. Today, the community sphere continues to foster solidarity and provides another level of identification for the individual. Some of these particular identifications can be chosen, but often an individual is born into certain cultural, ethnic or familial milieus. An individual’s hestian composition is unique, and depends on how these particular solidarities are independently experienced in both time and place. Even within the most intimate of solidarities, there exists differences and nuances. The polis sought to produce a commonality and present itself as a unified whole. Unfortunately, the formation of the polis created a split loyalty for the Ancient Greeks in which, instead of incorporating and fusing, the customs attached to the domestic hearth were denied in regards to the demands of the community. Originally, these demands were not dissimilar, but over time, the demands of the polis exceeded the sacredness of the familial home in favour of belonging to the civic realm (Wiles 1999:75; Hall in Kitto 1994:xxv). Instead of synthesising the domestic hearth and reconciling its needs with the needs of the polis, the demands of the polis relegated one sphere in favour of the other.

Perhaps the polis in the word ‘cosmopolitanism’ is antithetical as it distinguishes between inclusion and exclusion. For the Ancient Greeks, the polis was a sphere of possession and exclusion, a man-made construct where membership was conditional: ''Citizenship of the Greek polis was a status and a practice not available to all; this ideal of political belonging is a conception of citizenship in which the citizen is defined against the non-citizen" (Edwards 2015:10-11). The exclusionary nature of the polis is antithetical to Seneca’s notion of ‘cosmic belonging’. Cosmic belonging is natural: it is not conditional, is not dependent on prescribed behavioural mores, and does not discriminate. When the political understanding in Edwards’ quote above is expanded to the cosmic level attached with the term ‘cosmopolitanism’, this conceptualisation becomes the distinction between human and nonhuman or, even more problematic, subhuman (which is still being used to describe certain ethnic groups today). It could be argued that the use of ‘cosmopolitanism’ is actually a term of division, as the tenuousness associated with the political sphere is antithetical to the impulse for cosmic belonging. The switch from a hestia-centric mentality to a polis-centric mentality shifted the focus from inclusion to exclusion, from sharing with others to an ownership of possessions, where property was valued above beings. Thus, the ‘outsider’, or xenos, came to be viewed with suspicion, fear or derision. Koziak argues that the ‘drive toward the polis was partly based on the example of xenia’, yet, as the polis continued to encompass more areas of human interaction, xenia came to be seen as a threat to the polis (2000:129). Therefore, while the domestic sphere accurately depicted the unconditional inclusiveness of belonging to the world hearth, the creation of the polis―the community sphere of ‘conditional’ belonging― created ‘siloed’ identities that rejected and placed value on human life. The extension of the polis into states, nations and countries, further exasperated the division between ‘us’ and ‘them’. It would seem, then, that at the heart of the cosmopolitan ideal is the necessity to recognise and reconcile xenia.

Recognising and Reconciling Xenia

Ideally, the pursuit to recognise cosmic belonging would follow a linear trajectory: where an individual progresses from the familial sphere to a recognition of membership into a communal sphere (exhibiting multiple expressions of belonging), then to an understanding of a national identity (one that allows freedom to critically analyse diverse political structures), and ultimately to a rediscovery of the innate bond with all humankind (see figure below).

An organic progression would see the individual, when fully established and confident within one hestian sphere, move willingly toward the boundary of another sphere (a sphere ready to receive the ‘outsider’) and glimpse the unfamiliar; not with fear, but with curiosity and wonder―a desire to learn more about the unknown with the assurance of return to the previous sphere. But this is a utopic or elitist point of view. There is often a disruption to this linear progression, where the individual becomes trapped in one hestian sphere, or the introduction to the ‘unfamiliar’ happens abruptly, or the impossibility of return threatens an individual’s sense of security.

If we adhere to the ontological notion that we inherently belong to the world hearth, then being able to recognise xenia is crucial at every hestian level: it is the necessity to make the foreign familiar. An individual is constantly reconciling the ‘foreign’ on a smaller scale throughout the progression toward a realisation of belonging to the world hearth. The unknown ‘other’ is only ‘other’ until made familiar. From what we understand, the Ancient Greeks originally saw the initiation of a stranger at the hearth as a bond of equal reciprocity between the guest (xenos) and the host (xenos). The use of ‘xenos’ to describe both the guest and host attests to foreignness experienced by both parties: as the guest is foreign to the host, so, too, the host is seen as foreign by the guest. Both parties experience a vulnerability in the confrontation of the other: the person away from home is vulnerable and exposed, dependent on the hospitality and initiation offered at another hearth; while the host must reconcile the ontological disruption caused by this encounter with the foreign: the familiar has become unfamiliar. Neither party will return from this encounter the same, destabilising their sense of dwelling in the world – helping to establish that ‘right relationship’.

The xenia relationship, formed between two strangers of equal status, is the most complex of non-kin bonds. The xenia bond was intended to reconcile this disruption by establishing a pact that sought to unite diverse collectives through acts of reciprocity and emotional support. The hearth, therefore, exemplifies the transformative quality where non-kin (foreigners) become part of an individual’s hestian composition (familiar). Nussbaum claims that the xenia bond is the ‘most binding tie that exists by nomos [law], the tie that most fundamentally indicates one human’s openness to another, his willingness to join with others in a common moral world’ (1986:406). The notion of ‘binding’, ‘tie’, and ‘join’ in a ‘common moral world’ validates the interconnectivity experienced in cosmic belonging. Integration of foreign members to the hearth was designed to create a bond of mutuality through the hestian understanding of belonging. Barbara Koziak contends that the xenia bond was a ‘method of creating artificial kinship ties’ (2000:129) and Herman argues that the xenia relationship creates the illusion of kinship, where the members display an ‘outward manifestation of respect’ and act ‘as if’ they are related (1987:17, 33). Thus, the hearth, the place where a xenos became philos, was the site of recognising cosmic belonging.

The xenia bond is included as the only non-kin relationship regulated by the unwritten laws as a means of generating compassion, because, as mentioned above, to be without a hearth is to be without the fullness of being. Initiation at the hearth created a shared identity, and offered the warmth of a hearth to the one away from home. Joseph Wilson contends that the conflation of the term xenos signifies how both guest and host create a compulsion toward ‘mutual interdependence’ (2004:55). Mutual interdependence is another way of articulating the idea of cosmic belonging. The notion of ‘mutual interdependence’ is evident in that the host’s responsibility to protect a foreigner was equally the guest’s obligation to respect the host’s hestian structure. Herman argues that this obligation ‘exercised a constraining effect on behaviour’ (1987:122). The constraint resides in the host’s understanding that at some point she/he could be stranded in a foreign land in need of shelter and protection. Martin posits that: "Any “stranger” was a potential “guest”—and had to be so treated—any “guest” was by implication a potential “host” as he was expected to pay back whatever treatment was received" (2004:xliii). In this way, the xenia bond, dependent on reciprocity, mutual protection, and affection, attempts to reconcile the fear of disconnection and homelessness.

An individual confronted with assisting the unknown has one of two options: reject or respect. Kearney and Semonovitch (2011), in their introduction to their edited book Phenomenologies of the Stranger: Between Hostility and Hospitality, suggest that: "From the beginning, the xenos puts us in question and we respond with a word of welcome (xenophilia) or rejection (xenophobia). Faced with the xenos, we are compelled to make a wager between hospitality and hostility." (5)

The introduction of the other calls in to question an individual’s established understanding of dwelling in the world. Hospitality occurs when the individual is secure enough in her/his own hestian composition to reconcile the feelings of fear and fascination experienced through encountering the foreign. Hostility, on the other hand, stems from either fear― fear that this unknown entity will somehow ‘contaminate’ what has been traditionally ‘one’s own’― or the failure to reconcile one’s own vulnerability of dispossession, which prevents an individual from recognising ‘self’ within the displaced ‘other’. The inability to recognise the self within the ‘other’ impedes compassion.

Compassion is not merely a feeling – although it must begin with an understanding of immediate need – but, more, it requires an action to help restore the individual to a state of belonging. Compassion is dependent on an individuals’ ability to feel empathy for another; in the case of the hikiteia, or the one seeking refuge, to imagine what it would feel like to be displaced or exiled. If is it true, as Daniel Goleman suggests, that human beings are wired for compassion (2011), then what causes the recurrent refusal of people seeking asylum or refuge? Could it be that the obsessive clinging to a singular understanding of self― the inability/refusal to recognise cosmic belonging―limits our capacity for compassion and growth? Goleman states: "Self-absorption in all its forms kills empathy, let alone compassion. When we focus on ourselves, our world contracts as our problems and preoccupations loom large. But when we focus on others, our world expands. Our own problems drift to the periphery of the mind and so seem smaller, and we increase our capacity for connection - or compassionate action" (2011:54).

Self-absorption prevents an individual from ‘feeling with’ the displaced ‘other’ and perpetuates a xenophobic mentality. Self-absorption is a polis-centric disease. The Westernised political spheres and social structures have established an illusory alternative to cosmic belonging. This alternative deludes ‘first world countries’―a highly offensive distinction― into believing in the immutability of their circumstances; a false security of invincibility and permanency. The polis elevates the idea of eternal ‘belonging to’ a specific region/identity over the idea of ‘belonging with’ fellow human being, and in its construction the xenos became dangerous: a threat to an established and fixed identity. Therefore, the ability to recognise and reconcile the xenos, requires a negotiation of one’s own hestian composition in order to realise the interconnectedness of all living beings. It could be argued that, on a cosmic level, the ‘other’ does not exist. However, in the empirical reality, individuals do encounter the foreign, which causes them to reconsider their own understanding of dwelling and essentially forces them to see themselves as xenos. In other words, recognising the xenos is recognising one’s own foreignness: a consciousness of one’s unique hestian composition.

Conclusion

Positioning hestian notions of belonging and interconnectivity as central to cosmopolitanism reimagines four key philosophical impulses. Firstly, understanding the earth as a world hearth unites all beings into a cosmic whole. Recognition of the interconnectedness of all beings is crucial for debunking artificial constructs of the ‘other’. Secondly, the centralising of the hearth recognises the world hearth as ontologically first, yet psychologically last to be realised. In this way, the impulse for cosmopolitanism is an instinct to return to, as Seneca proclaimed, a more natural state of being. An individual must progress through more particular identities in order to arrive at the ontological beginning. In this way, the more particular spheres of family, city, state, and nation should serve to assist an individual in progressing toward a rediscovery of cosmic belonging. Thirdly, the repositioning of hestia at the centre places value on compassion and cooperation over competition and domination. Compassion is necessary to counter self-absorption and polis-absorption, where an individual becomes consumed in one particular way of viewing the self and denies cosmic belonging. Lastly, a hestia-centric focus perceives the ‘foreigner’, not with fear and suspicion, but through an understanding of their own individual ‘foreignness’; a recognition of their own unique hestian composition. Failure to recognise the self within the other leads to xenophobic behaviour and stereotypes. Ultimately, the distinction between a polis-centric and a hestia-centric focus lies in the notion of cosmic belonging eclipsing the man-made institution of citizenship.

Literature

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Belfiore, E. (1998). ‘Harming Friends: Problematic Reciprocity in Greek Tragedy’, in CJ Gill, N Postlethwaite, R Seaford (eds.), Reciprocity in Ancient Greece. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Benvenuto, S. (1993). Hermes-Hestia: The Hearth and the Angel as a Philosophical Paradigm. Telos. June, pp.101-118.

Brill, S. (2009). ‘Violence and Vulnerability in Aeschylus’ Suppliants’ in W Wians (ed.) Logos and Muthos: Philosophical Essays in Greek Literature. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Brock, G. (2014). Greek Tragedy and the Poetics of the Hearth (unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of the Sunshine Coast. Maroochydore, Australia.

Burnet, J. (2003). Early Greek Philosophy 1892. USA: Kessinger Publishing Co.

Calhoun, C. (2003). ‘Belonging’ in the Cosmopolitan Imaginary. Ethnicities. Vol3(4). London: Sage Publications.

Croally, N. (2007). Euripidean Polemic: The Trojan Women and the Function of Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Detienne, M. (2002). The Writing of Orpheus: Greek Myth in Cultural Context. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Edinger, E. (1994). The Eternal Drama: The Inner Meaning of Greek Mythology. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Edwards, M. (2015). The Limits of Political Belonging: An Adaptionist Perspective on Citizenship and Society. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goldhill, S. (1986). Reading Greek Tragedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goleman, D. (2011). Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships. London: Arrow Books.

Hall, E. (1994). Introduction and notes. In H.D.F. Kitto (trans.) 1962 Sophocles: Antigone, Oedipus the King, and Electra. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1942). Holderlin's Hymn ‘The Ister’ in W McNeill & J Davis 1996 (trans.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, M. (1954). Building Dwelling Thinking in S Meagher 2008, Philosophy and the city: Classical to Contemporary Writings. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Herman, G. (1987). Ritualized Friendship and the Greek City. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Homer. Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns and Homerica. In HG Evelyn-White, {Trans.) 2008. Stilwell, KS: digireads.com Publishing.

Kearney, R. and Semonovitch, K. (2011), Phenomenologies of the Stranger: Between Hostility and Hospitality. New York: Fordham University Press.

Kleingeld, P. (2012). Kant and Cosmopolitanism: The Philosophical Ideal of World Citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koziak, B. (2000). Retrieving Political Emotion: Thumos, Aristotle, and Gender. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Martin, R. (2004). ‘Introduction’, in E McCrorie (trans.), Homer’s Odyssey. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Meagher, RE. (2002). The Essential Euripides: Dancing in Dark Times. Illinois: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc.

Mikalson, JD. (1991). Honor Thy Gods: Popular Religion in Greek Tragedy. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

Naiden, FS. (2006). Ancient Supplication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (1986). The Fragility of Goodness: Luck and Ethics in Greek Tragedy and Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2002[1996]). ‘Patriotism and Cosmpolitanism’. In MC Nussbaum, For Love of Country, pp1-17. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Plato. The Laws in B Jowett (trans.) 2009. Stilwell, KS: digireads.com Publishing.

Rehm, R. (2002). The Play of Space: Spatial Transformation in Greek Tragedy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Songe-Moller, V. (2002). Philosophy Without Women: The Birth of Sexism in Western Thought. London: Continuum.

Stamatellos, G. (2012). Introduction to Presocratics: A Thematic Approach to Early Greek Philosophy with Key Readings. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Starr, C. (1986). Individual and Community: The Rise of the Polis 800-500 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tankha, V. (2006). Ancient Greek Philosophy: Thales to Gorgias. India: Dorling Kindersley, Inc.

Thibodeau, M. (2012). Hegel and Greek Tragedy. Maryland: Lexington Books.

Thompson, P. (1996). Re-claiming Hestia: Goddess of Everyday Life. Philosophy in the Contemporary World. Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 20-28.

Tzanetou, A. (2012). City of Suppliants: Tragedy and the Athenian Empire. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Vernant JP. (2006). Myth and Thought. New York: Zone Books.

Weil, S. (2002). The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. London: Routledge.

Wiles. D. (1999). Tragedy in Athens: Performance Space and Theatrical Meaning. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Wilson, J. (2004). The Hero and the City: An Interpretation of Sophocles' ‘Oedipus at Colonus’. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

This keynote speech draws from Brock's article 'Cosmopolitanism Beyond the Polis: Creative Memory Works and Reimaging the Relationship between Hestia and Xenia', which was published in the book entitled Beyond Cosmopolitanism: Towards Planetary Transformations (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), edited by Ananta Kumar Giri.