Success factor

Dutch artists and organisations continue to excel in creating compelling and cutting-edge arts for children: from the persistent success of writers like Dick Bruna in Japan, Annie M.G. Schmidt in Russia and Edward van de Vendel in Africa, to the recent triumphs of Dutch youth films at leading international festival, such as Astrid Bussink’s Listen (ECFA short film award, Short Film Festival Oberhausen 2018), Steven Wouterlood’s Mijn bijzonder rare week met Tess (i.e. Crystal Bear, Berlinale 2019) and Johan Timmers’s Vechtmeisje (Academy Young Audience Award 2019).

Successfully speaking to the minds and imaginations of an increasingly diverse young generation, this unofficial discipline is booming in many different sectors, and not just domestically. A potential explanation for the international success is Dutch makers’ ability to speak to and represent a modern, multicultural society – something one could recognise in, for example, the nominees of the Gouden Krekels for youth theatre, which are often far more culturally diverse than those of, for instance, the Louis D’or.

On October 18, in collaboration with Cinekid, The Performing Arts Fund NL, The Dutch Foundation for Literature, The Museums Association, The Netherlands Film Fund and the Dutch Association for Performing Arts (NAPK), DutchCulture organised a conference on international children’s culture based on the idea that there is a meaningful relation between makers’ ability to communicate interculturally and their international success. The central question underlying the keynote speech, panel discussion and all the smaller sessions was: how do you address the stories, images and questions of both internationally and interculturally diverse audiences of children?

Researchers Errol Boon and Simon de Leeuw attended the conference asking: how do you ensure that the evoked imagination within your work is both interculturally inclusive and internationally successful? Can we identify the strategies or approaches that make Dutch artists so skilled in this field?

Universal versus particular

Why a conference on kids’ culture? Unmistakably, one of the beliefs informing a conference of children’s culture is that we need to take a distinct perspective on audience outreach when we talk about kids’ culture. However, despite its self-evident character, it turns out to be particularly difficult to explain this basic assumption. During the conference, two accounts of the distinctiveness of kids’ culture were addressed, both very plausible but also seemingly contradictory. On the one hand, we find a vital plea for the universality of childhood, especially addressed in the keynote speech of Segun Adefila; on the other hand, especially during the panel discussion, the distinctiveness of kids’ culture was rather explained concerning the particularities of specific cultural circumstances. Interestingly, these seemingly contradictory explanations can both be true at the same time.

Let us have a closer look at both sides of the paradox of kids’ culture. On the one hand, we could say that in appealing to a new audience, every artist presupposes a shared (universal) imagination. Within culture for kids, this universality seems more important, often even decisive, for the way makers approach their audiences. In his keynote speech, Segun Adefila (director of Crown Troup of Africa in Nigeria), emphasises this universality of childhood, which, to him, exists first and foremost in the children’s quest for freedom, innocent selfishness and desire to play. While they are no tabula rasa, it seems valid to say that children share more with one another than their parents, who are already thoroughly embedded in the particular culture they live in. Therefore, children’s culture is distinctive because it needs to anticipate the universal character of childhood.

On the other hand, however, a truthful approach to children and children’s culture also require a culture-specific analyses – something to which also Adefila is hinting when he quotes the Yoruba saying Oju merin ni n bimo, igba oju ni n wo, meaning ‘a child is the product of the fusion of four eyes but the child is nurtured or trained by two hundred eyes.’ When explaining why kids’ culture requires a distinct perspective, one might point to the fact that whereas adults enjoy at least a relative autonomy in their encounter with cultural products, children are essentially dependent on the adults that determine (i.e. select and adapt) the children’s access to those artworks.

In the panel discussion of the conference, Mylo Freeman, Tessa Leuwsha and Elsje Kibler-Vermaas therefore repeatedly underlined the decisive role parents play in children’s access to culture. The point is that in children’s arts societal, cultural and material conditions – the school systems, deeply-rooted traditions, economic systems, etc. - play a far more decisive role than in the case of adults, who can have relative independence from these conditions. Thus, considering kids’ culture must involve a consideration of the particular society the child lives in – after all, for children a notion like l’art pour l’art would not make any sense at all.

The paradox

Hence, the paradox is as follows. On the one hand, children’s culture-makers are appealing to something like a universal language of childhood that precedes cultural differences, on the other hand, more than in the case with adults, it seems to be necessary to adapt works of children’s art to particular cultures (e.g. encoding a work of art to the specific symbolism and signifiers of that audience). When telling stories to children, probably more than in the case of adults, an artist is both able to address the higher kinship of children among different nations – making those stories potentially relevant to children all over the world – but, on the other hand, an artist has to also depart from the specific cultural background and situatedness of the child.

As said, this is merely a seeming contradiction, as the concrete praxis of artists working in the field testifies how both accounts make up perfectly two sides of the same blinking coin of children’s culture. We can recognize this paradox, for example, in the dialectics between parents and children in their collaborate encounter to culture. It is, for example, often claimed that for a cultural institution to reach a local community, one should ‘start with the kids’ (after which also the sceptical adults will join). The paradox we described is exactly that these kids, however, can only reach the institution through their parents. The parents are brought by the children, who are in turn, brought by their parents. We could say that the universality is situated in a culture, which in turn is a modification of universal forms. Let us now look at some more concrete examples from the conference.

The praxis

Elsje Kibler-Vermaas, vice-president of Learning at the Los Angeles Philharmonic, tries to bring children from the various cultural background into contact with classical music. She employs a more universal ambition – which is that independent of where it grows up, every child should be able to experience classical music – but in each case, she does this with a new, tailor-made approach, taking into account the children’s specific cultural background. In doing this, she even challenges herself to make music with the most diverse group possible, often existing not only of ‘children that never heard of Mahler, but never even touched an instrument.’

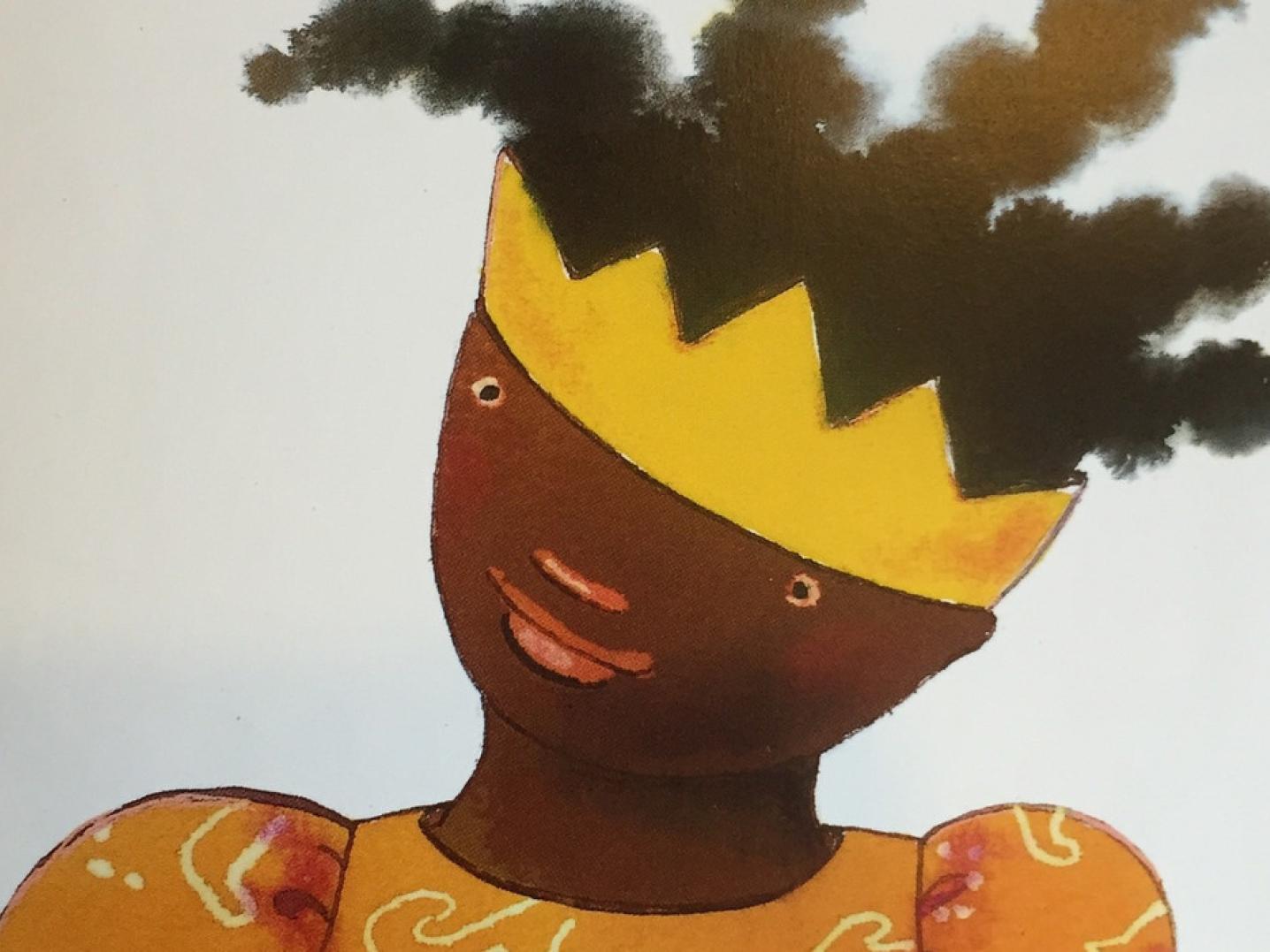

The same applies to Mylo Freeman, who, in her quest to create new icons in children’s stories, makes beautiful children’s books about the black princess Arabella. Despite her universal engagement and approach, she receives different reactions to her book all over the world. Every time she visits schools to tell the story of an unhappy princess, despite having everything she can imagine, she asks the class of children what it is that the princess needs. Most kids in Western countries give typical answers: a crown, a play station, a swimming pool. However, when Freeman asked a classroom in Nigeria, the class remained silent. Only after a while, a girl in the back of the room answered: the princess needs a friend.

Tessa Leuwsha, who is a writer and the cultural attaché at the Dutch embassy in Paramaribo, concluded with some apt observations from her own experience. She holds that since most children live in the present and do not have a strong sense of history yet, they directly absorb what they see. What children of Surinam absorb from Dutch art are a lot of white faces on bicycles. For them, this galvanizes the idea that being white is a condition for being part of a documentary or ‘real’ story. That’s a pity, because Dutch culture is special and potentially valuable for Surinamese kids, exactly because Dutch makers tend to address more universal and complex issues (despite Surinamese kids culture, which is more moralistic). Therefore, Dutch kids’ culture shows Surinamese children a real world by addressing its universal issues, yet due to the codes, clothes, and colours they do not recognise themselves in it. As a positive counter-example, Leuwsha recalls ISH Dance Collective’s Jungle Book, which used a famous story that appeals to children from all over the world - but for the depiction of ‘the civilized city outside the jungle’, they used images of Paramaribo, so that the children of Surinam could recognise their life world.

In sum

Throughout the event, we could sense a strong recognition of the tendency of Dutch creatives and artists to take children particularly seriously as their audience, an idea also elaborated by IJsfontein’s Hans Luyckx in last year’s edition of the congress. While it is attractive to subscribe to this idea, it not a given fact nor a native Dutch trait. We should not overlook all the tinkering, the fine-tuning and the craft involved in presenting an artwork to young audiences embedded in a particular culture in a different country. The fact that Dutch institutes and artists – who shared their practices during the break-out sessions – know how to appeal to non-standard and non-homogenous Dutch audiences is a promising development with regards to their potential successes when crossing the border to present their arts internationally.

Thinking of the paradoxical distinctiveness of children’s culture it seems that a young audience is, on the one hand, much more free of ideological ideas and much less imbued by the moral convictions and cultural assumptions of their parents. However, despite this kinship of openness among children, we tend to be much more careful when it comes to conveying stories to children, as (moral) censorship is nowhere so accepted as in kids’ culture. It seems that kids are both uninhibited, open-minded, as well as more susceptible for a local cultural or ideological symbolic order.

It is not easy to draw out the defining difference between addressing children or adult audience. However, what prevails in the different examples discussed during the conference is that children’s future is still more open, whereas the life of a grown-up is already far more impregnated with meaning, determined by the heritage of a past that the child does not have yet. Thus, it may be for the very sake of that still relatively untouched open promise of the future, that we tend to approach children with much care of their situatedness. After all, those future audiences – not only within their imagination but also within the developing possibilities in the field of children’s culture - may create common futures.