No Seat at the Table: a graphic novel on gentrification in Turkey and the Netherlands

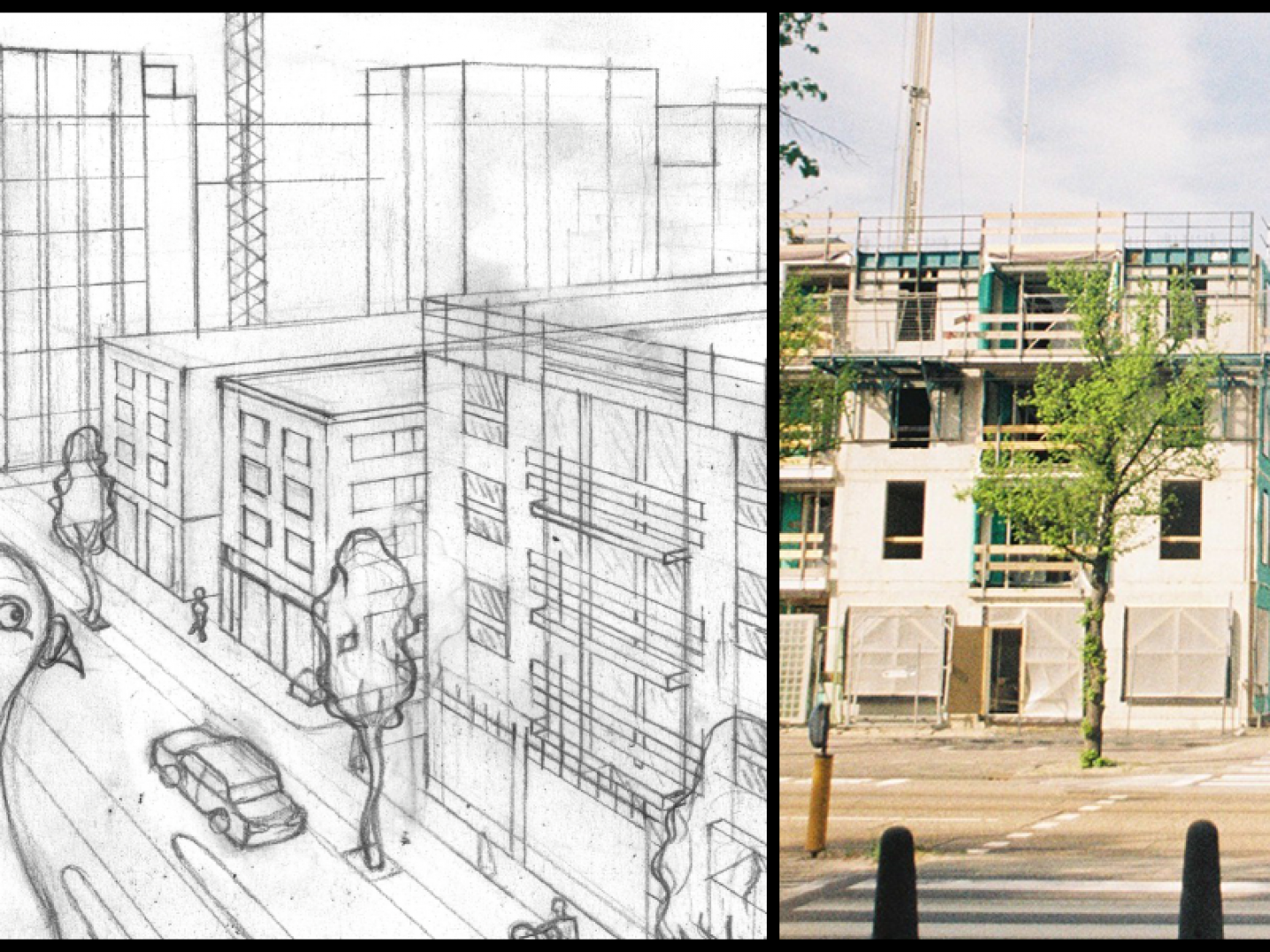

No Seat At The Table is a fictional graphic novel about the local and global influences of gentrification on citizens in Turkish and Dutch cities. The book highlights four neighbourhoods where this phenomenon is occurring: Piyalepaşa in Istanbul, Ismetpasa in Ankara, De Kolenkitbuurt in Amsterdam, and Lombok in Utrecht. The stories are told from the perspective of a pigeon. With this book, the team would like to start a conversation about the negative impacts of gentrification. The most pressing issues are forced displacement, the stigmatization of the residents in these districts by people in power, and the exclusion of low-income groups from the places where this urban transformation is taking place.

The core team consists of writer/project leader Minem Sezgin, illustrators Jasmijn de Nood (Amsterdam), Rajab Eryiğit (Istanbul), Bob Mollema (Utrecht) and Erhan Muratoğlu (Ankara), and book designer Murat Otunc and Vincent de Boer.

In this interview with Minem Sezgin we go back and forth between January and June 2020. We hear from Minem about her fascinating project No Seat at the Table, how COVID-19 has affected her plans and what type of solutions she has found to adapt to the ‘new normal’.

What do you hope to achieve with this book?

“We see this book as a tool for talking about gentrification. We want this book to trigger questions and conversations between people of different backgrounds about how we can make cities more inclusive and more affordable for all. This is also why we’re developing community activities.

And, I’m a first-generation migrant woman from Turkey. So, for me personally, this is also about being one of the representations for young women in the Netherlands and Turkey with diverse cultural backgrounds. It is important for me that they see me, someone looking like them, and think: if she is able to do it, I can too.”

Concerning gentrification, what exactly is the problem? And what are the similarities and differences between the four neighbourhoods where your stories take place?

“Gentrification is a big topic and has various effects, that can be seen as both positive and negative. We chose to focus on residential displacement, which is one of the many negative impacts of gentrification and one of the most urgent ones. In this case, the neighbourhoods that are being gentrified become less inclusive; the socio-economic structure of the area changes, and access to living there becomes affordable only to certain groups of people.

This phenomenon is state-led both in Turkey and the Netherlands and is conducted with very similar motivations, coming from neoliberal urban planning policies. Both countries promote the neighbourhoods to the international real estate investors in real estate fairs or by offering tax benefits. In a recent study analysing gentrification in the districts of Tarlabaşı in Istanbul and in the Indische Buurt in Amsterdam scholars pointed out there was a stigmatisation of the residents based on their ethnical background. Both states use exhaustion as a tool to push people out of their neighbourhoods.

One of the most obvious differences is that in Turkey the process is much more aggressive. For example, a building crane can show up in a neighbourhood quite suddenly and tear several houses down. In the Netherlands the process spans a much longer period which allows the owner to easily change housing contracts. These days ‘flexible’ contracts are used for shorter leases which constitutes a complete break with previous contracts that protected the renters’ rights. Not to forget that there are of course local differences between Lombok and De Kolenkit, and Piyalepaşa and İsmetpaşa. But we do not have enough time to delve into these other aspects.”

Are the communities living in these neighbourhoods in Turkey and the Netherlands affected in the same way?

“To a certain extent, yes. Even though the various approaches used by the municipality and the contractors involved in the gentrification are different, in all cases, different communities or certain groups of people are moving out of the neighbourhoods. In İsmetpaşa people would be pushed out more forcefully whereas in Piyalepaşa people would choose to sell the land they own and leave. In both places some people also left due to safety concerns caused by the rise in drug trafficking. In Lombok, higher classes would take over the neighbourhood as an ‘exotic place to live’ and in De Kolenkit, which was declared one of the most unsafe residential areas in Amsterdam a few years ago, the change is similar to that in Lombok, but more drastic. In these four neighbourhoods, the people that are forced out of their homes share similar anecdotes and socio-economic backgrounds.”

How has coronavirus affected your project, especially your international team, spread as it is across Turkey and the Netherlands?

“It has affected the project quite significantly. In general terms, the progress was slowed down and a third of our project needed to be cancelled. We were going to organise workshops with children and conversations with the residents about gentrification and fair cities around this time of the year in Turkey. It is unfortunate, we were looking forward to this period so much.”

Have you found new ways to do your work and stay connected to your audiences?

“After the cancellation of our events, we decided to adjust our outreach efforts. For the activities with children, we couldn’t create an alternative because they have a hands-on collective concept. For the dialogues/conversations, we started a blog on which the illustrators from each city share their impressions of our field trips. This blog is currently open for everyone to share their story as we think it is important to continue to our conversation with the residents of the neighbourhoods. We're open to all suggestions and possibilities regarding this online platform.”

What has the crisis taught you? Did it change your creative process?

“Maybe a very cliché thing to say but it taught me that anything can really change at any minute. When I look back, I can see the transformation was in a blink of an eye; from the moment of preparing for a 3-4 week long trip to the moment of cancelling all events. I'm glad that I acted on time as the project coordinator. The crisis taught me to be more flexible.

We’re experiencing something unprecedented and many things remain unclear. This is what makes it both very precarious and an opportunity to explore new possibilities of work and connection.

Having finished the graphic novel, I just really, really want to be able to visit the neighbourhoods, get to see the residents and talk about the book as soon as possible.

Your novel is based on stories of real people. How did you meet them?

“We couldn’t have developed our stories without the input of the residents of the four neighbourhoods. We usually met them on the spot while we were visiting and asked if they would like to talk to us. Of course we stressed that it was an independent art project, and that we would keep their anonymity. In the story of Ankara, I wanted the primary source of information about the neighbourhood İsmetpaşa to be based on the experience of the young girls I met there. I wanted their account to inform and influence the graphic story. I was deeply moved by their beautiful energy, their trust, the tour they gave us of their neighbourhood, our joyful conversation, and our friendship. More particularly, I was inspired by the contradiction between their warm attitude, the ruins in the neighbourhood and the perception of many people towards that neighbourhood.

We returned to Piyalepaşa, İsmetpaşa, De Kolenkitbuurt and Lombok several times and had many conversations with the residents about how their living environments were changing and how they were experiencing it. In all of the neighbourhoods there was precarity and frustration, because of the drastic increase in housing prices and the lack of affordable living in general. And even though diverse socio-economic groups are still living together, the interaction between these groups is less than it previously was. Most of the new residents are experiencing the neighbourhood in a different context: the solidarity and familiarity that used to exist has been diminished. The social structure of the neighbourhood has also changed because some residents who played an important part in the local community have left. There’s a feeling of distance in the new societal texture.”

What’s it like to tell a story which does not belong to you?

“I should admit that telling a story which is not mine was challenging because it does not directly belong to me. Especially because my experience of gentrification is on a completely different level. Although I am aware of the fact and experiencing how cities are becoming less and less inclusive, I am not being forced out of my home.

During our team meetings, we had many conversations and engaged in self-reflection about our approach and the most ethical way to use these stories. How can we make sure that we are not just taking the stories and walking away? How could we tell these stories in the most appropriate way, with much respect? I think it is important to always keep these questions in mind. Until now our project was very well received by the residents. Our experience is really positive.”

Why did you choose this particular medium – a graphic novel – to talk about gentrification?

“I studied political science and political communication. In my art projects I want to create more empathy amongst people and bring an added value to the society. I am a storyteller, I write stories and one of them took the form of this graphic novel on gentrification.

The topic of gentrification is the subject of so many fascinating articles, books, documentaries and films, which we researched extensively beforehand. We chose the graphic novel because it gave us the freedom to create a fictional world, not only verbally but also visually. The topic is quite broad and can be complex; the graphic novel also helped us to communicate our message in a more approachable way.”

How did you select the illustrators?

“I selected the four illustrators personally. There is one from each city to visualise that city’s story because I wanted to add a layer of their personal connection to their cities. Each of them has a personal and unique style and is committed to telling stories with an important message. These were the most important elements for my selection.”

Can we expect something new from you soon?

“Yes, I am writing a TV-series about a woman from Turkey moving to the Netherlands. It is a dark comedy on how she is experiencing this new world, and by doing so, re-discovering herself in her late 20s. I am at a very preliminary stage, I am collecting bits and pieces. I hope to have the opportunity to develop this further in 2020.”

Partners of No Seat At The Table are: Creative Industries Fund NL, the Netherlands Institute in Turkey (TR), architectural firm Studyo 501 Mimarlik (TR), creative collective Zitlar Mecmuasi (TR), cultural centres RAUM (NL), Podium Mozaïek (NL) and De Voorkamer (NL).

For funding possibilities, check out our Cultural Mobility Funding Guide or the websites of our partners EYE International, Film Fund, Performing Arts Fund NL, Het Nieuwe Instituut, Dutch foundation for Literature, Mondriaan Fund, Creative Industries Fund NL, the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Ankara and the Consulate General in Istanbul.

Check out the complete overview of Dutch cultural activities in Turkey in our database. If you are a cultural professional who wants to go to Turkey, feel free to contact our Turkey advisor Yasemin Bagci. If you have questions about cultural cooperation with Turkey during corona, please visit our special information page.