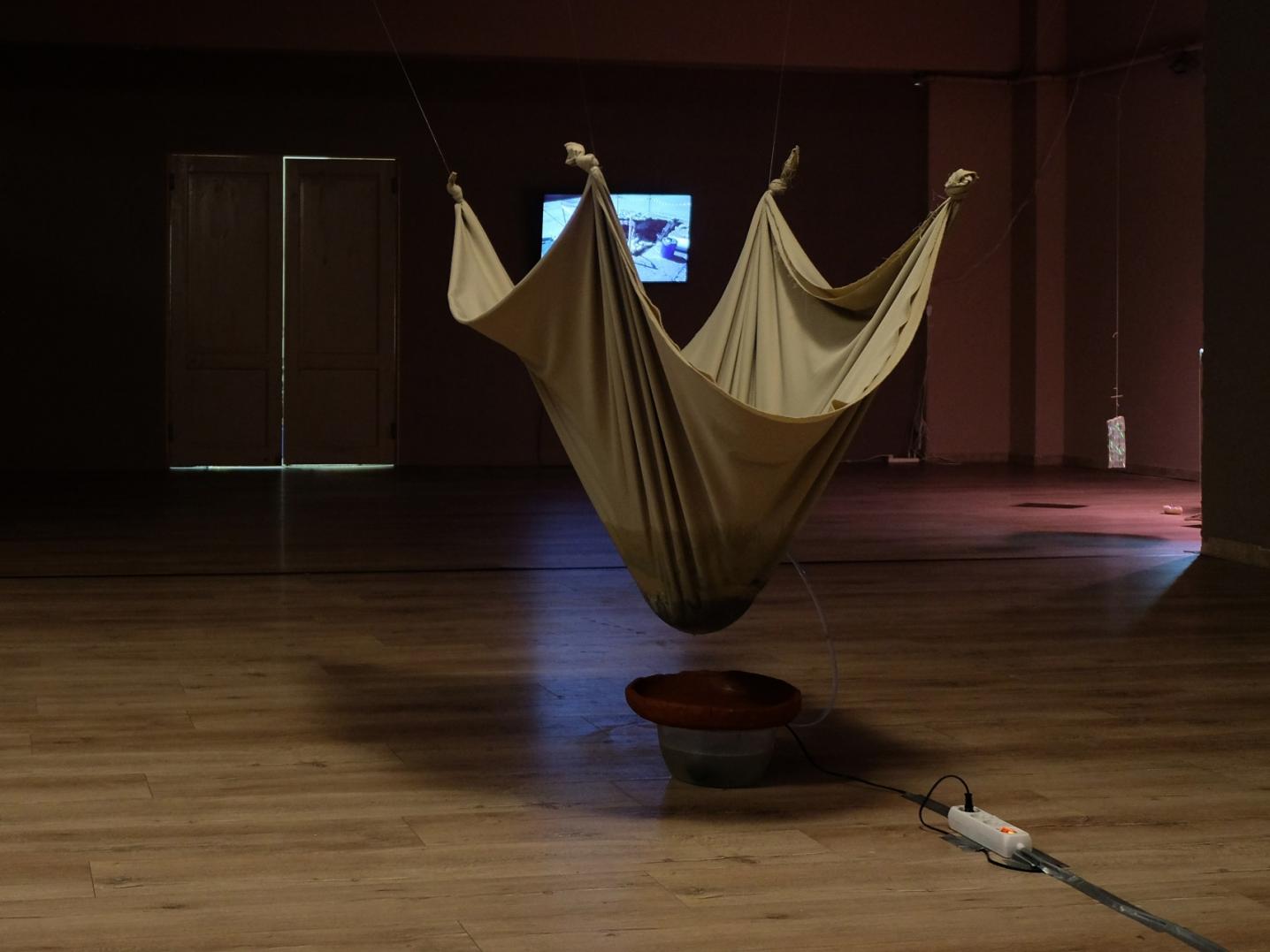

This meeting's goal was to make room for the perspectives of young Moroccan and Dutch-Moroccan artists and cultural professionals regarding the exhibition The Other Story: Moroccan Modernism from 1956 till now. Therefore, we invited four young Moroccan and Dutch-Moroccan artists to shine their light on the works and themes presented. Author and curator Abdelkader Benali acted as moderator.

For photographer Sarah Amrani this was a rather personal exercise since her Oujda series was included and one of her photographs was the ‘hero image’ of the entire exhibition. She was surprised when curator Abdelkader Benali contacted her via Instagram. Amrani: “It was so informal, for such an official opportunity. For me, it was a full circle moment to see my own work next to Lalla Essaydi’s, who reclaims the orientalist image of Moroccan people. Her portraits of women are very layered in both a material and non-material sense.”

We were also very pleased to welcome Chama Tahiri from Casablanca. She is a cultural mediator and creative producer, who played an important role in the local production of a cultural mission to Morocco organised by the Municipality of Amsterdam and DutchCulture. It was supposed to take place in 2020 but had to be called off because of the pandemic, but we are striving to reschedule it in 2023.

The spirit of Casa

Throughout the programme, Tahiri was eager to share her insightful views on recent changes in the Moroccan arts world: “Around eight years ago, I saw how a new generation of artists was struggling to find space to share their work and make new connections. It became my drive to create a network and a place for cultural exchange.” In 2021, she opened NIYA – the first vegan restaurant in Casablanca – where she also hosts book clubs, yoga sessions and open mic nights.

Last April, Tahiri wrote Reclaiming Casablanca for DutchCulture’s magazine on the city’s art scene in which she highlighted the work of our third guest. During the panel discussion, Mohammed El Bellaoui – also known as Rebel Spirit – called in from his studio in Casablanca. In his early work, he depicts a character called Madini, who guides you through his home city. Rebel Spirit: “Casablanca is nothing like the rest of Morocco, it’s very open and vibrant. The spirit of Casa tells you to either take it or leave it, you must react instantly.”

Our fourth guest – visual artist Salim Bayri – was also born and raised in Casablanca, but studied in both Barcelona and Groningen before he was selected for the Rijksacademie in Amsterdam. Bayri, who is nominated for de Volkskrant Beeldende Kunstprijs 2022, was struck by the work of Dutch-Moroccan artist Nour-Eddine Jarram, even though he represents an older generation.

Where to start?

After visiting the exhibition together, a smaller group of artists, cultural professionals and heritage students stayed for the second part of the programme. Together with Benali, DutchCulture’s Morocco Advisor Myriam Sahraoui and three of the guest speakers they discussed Dutch-Moroccan cultural exchange in more depth. In this more intimate setting, they talked about their experiences with building and maintaining a network, and how both formal institutions and social media contribute to developing their artistic practices.

Attendee and Dutch-Moroccan visual artist Samira Serghini is excited and anxious to start collaborations in Morocco. She asked the panel speakers: “I’m only familiar with the traditional side of Moroccan culture through my family but encounters with Moroccan contemporary artists have been a totally different experience. There are so many differences in language, perception and taboos. Can I just travel as an individual female artist to Casablanca and dive in?”

Moderator Benali recognises this feeling. “The cultural field of Morocco is confusing. Despite my personal connections, it’s hard to keep track. But I learned a closed door doesn’t mean it’s not going to be happening. It’s just not going to happen the way you expected it to. The rhythm in Morocco is just different, it’s important to go prepared and to be patient. For me, contact with the locals is the key.”

Bayri chips in, noticing that Europeans who visit Morocco for the first time often perceive a ‘chaotic’ country: “But this is a misconception. People have been living this way for thousands of years and it still works; you just don’t know the codes of this system yet. Show some humility and stop thinking in basic transactional currencies. We make art in order to find other kinds of currencies.” As Tahiri illustrates: “For the French, ‘le souk’ means chaos. But it’s very structured. Then I wonder: according to whom is this chaotic, whose standards do you apply?”

Tahiri’s advice to Serghini is to be open: “The best way is to take your time and meet the locals. Many Moroccan artists have studied or travelled abroad and are willing to connect. Go with the flow and you’ll be invited to meet lots of other interesting people.” Cafés like NIYA play an important role in encountering locals and meeting like-minded creative people.

Networking via Instagram

In 2018, Sarah Amrani was invited via Instagram for her first Moroccan exhibition. And she’s not the only one. “Young Moroccans spend a lot of time on the internet, which can be a safe but sometimes brutal space. Young artists with unprivileged backgrounds perhaps don't have access to art institutions, but they find new collaborations through Instagram,” Tahiri says. “Moreover, there’s an increasingly thin line between what's considered 'art', and content creation.”

Thus, they also find new audiences via Instagram. Benali was surprised by the high number of Instagram followers the controversial photographer Fatima Zohra Serri has, even though she lives and works in the conservative city of Nador. Tahiri explains: “Some Moroccan artists [like Serri, ed.] aim for a better representation of the country, with a focus on Moroccan audiences. But often, they reach a point where it’s not enough, and it becomes more interesting to extract themselves from this and focus on a new and universal language, and international audiences.”

Controversiality

One of the attendees wonders whether Amrani has ever been confronted with negative reactions to her work, since the Oujda series depicts the anonymity and intimacy of a bride’s preparation for her wedding ceremony in a rather unconventional way. But so far, Amrani hasn’t. As Tahiri explains: “In a way, elite art depicting controversial themes is harmless because the people who have access to highbrow galleries are not going to be shocked since they’re already familiar with these topics.” Nevertheless, Amrani says it’s important to her to stay open to different interpretations of her work.

Bayri agrees: “I’m very careful about imposing on an audience what to see or feel. Unlike most modernist painters of the School of Casablanca around 1969, who thought they could explain to peasants what real art should be. How arrogant is it to decide for someone else what to think?” He sometimes struggles to find a Moroccan audience that is really interested in his work. “I’m not looking to reach the majority of the Moroccan population, because they are rather conservative. At the end of the day, few people dare to say or do something outside the establishment. Sometimes it feels like it’s not the right place or time to say something, so then I wait for a better moment.”

“In Morocco, free speech exists in a misleading way,” elaborates Tahiri. “There are just three things we don’t talk about: religion, the kingdom and the Sahara. You can address pretty much any issue, as long as you don’t annoy powerful institutions or people. But at the same time, the main social issues are not represented enough in galleries, like racism against black Moroccans.”

Formal structures

Especially young Moroccan artists have financial constraints since access to institutions and funding is lacking. Tahiri: “This brings a sense of urgency which can be a good thing because nothing great is created out of comfort. On the other hand, I would say: go get the money where it is but stay grounded. Like Rebel Spirit, who is still connected to the neighbourhood where he comes from, but also mingles with the highbrow art scene. He even sold his work to King Mohammed V.”

DutchCulture’s Morocco advisor Myriam Sahraoui emphasises the importance of formal institutions in the collaboration between Morocco and the Netherlands. Sahraoui: “In 2018, we took the first baby steps towards a more profound cultural exchange. We planned a cultural trip to get to know the arts and culture in modern Morocco, but then the pandemic hit. There was no funding or support for the Moroccan cultural field whatsoever, it felt like two years of the desert.” This spring, we finally managed to organise an exchange as preparation for a training programme for museum professionals from the Moroccan Fondation Nationale des Musées and the Reinwardt Academy in the Netherlands. The exhibition The Other Story is one of the first concrete results of this shared effort.

The colonial attitude

Another issue Benali was confronted with during his frequent trips to Morocco, was the influence of French governmental structures and culture. “As a Dutch person, I was shocked by the French framework in Moroccan society. Some Moroccan artists have inherited a distant attitude towards their own heritage and culture. They talk about Morocco as if it’s a foreign country.”

Tahiri agrees: “This French attitude of arrogance and spite towards people of other classes has become ingrained. Some French people still have a certain domineering attitude towards Morocco as a former colony, as if they still own it. But we should stop defining ourselves through western gazes. Morocco has been orientalised and fetishized for long enough. We need collective psychotherapy.”

Born and raised in the Netherlands, Serghini feels intimidated by the history of colonialism. She is probably not the only one of her generation whose discomfort is an obstacle to creating space for new perspectives. Sahraoui advises: “It’s important to not let yourself be imprisoned in mental, intellectual concepts. If you go to Morocco, try to feel the ground when you’re there, instead of remaining occupied by ideas in your head and your western way of thinking.”

The time is now

A certain openness towards working with Dutch artists and cultural professionals seems to be growing recently. Tahiri agrees: “For me, it was refreshing to work with Dutch people, who were interested in what I have to offer instead of assuming they needed to teach me something.” Finally, Myriam Sahraoui has one more thing to say to Dutch-Moroccan artists like Samira Serghini: “Go for it, the time is now.”