The International Queer and Migrant Film Festival (IQMF) aims for an inclusive society in which people of all genders, sexual preferences and nationalities enjoy equal human rights, freedom of movement and fair representation in the media. DutchCulture is a partner of IQMF and co-organized the talks Queer Artivism, the Moroccan Perspective and Festivals for Freedom that took place during the festival. On Sunday, the talk Safe Art Spaces: The Balkan Approach took place with DutchCulture Cees de Graaff, as one of the speakers.

In the early afternoon on December 7, just before the first screening is about to start, the festive LAB111 in Amsterdam is still quiet. Soon the spacious bar, screening rooms and exhibition spaces will be filled with people, looking at art and socializing in many different languages. The festival attracts an international audience, that is both young and older, queer and not.

Shelter – Farewell to Eden

The first screening we attend is Enrico Masi’s documentary film Shelter – Farewell to Eden. In the film, we follow Pepsi, a Muslim transgender woman, in her flight from the Philippines to different places and countries. The film is disorienting as it provides no clear descriptions of locations or time. The lack of the documentary’s linearity or clarity is frustrating at first, but comes with the uneasy realization that it suggests only partially the disorientation and complete uncertainty that Pepsi faces. We see how she mostly walks from one country to another, as it is safer and cheaper than going by train, boat or car through a trafficker. Pepsi recounts her experiences with homelessness and sexual abuse, and she assures us that the forest is a safer space for her to be in than the city – which says a lot about our current social services and immigration policies. The documentary underscores the necessity of IQMF; it is very important that we consider marginalized sexualities and gender identities as interrelated with immigration. Shelter – Farewell to Eden exposes the dire situation of (queer) migrants that is often downplayed or ignored.

Festivals for Freedom

During the talk Festivals for Freedom, festival organizers and filmmakers Leyli Gafarova (Azerbeijan), Masha Godovannaya (Russia), Popo Fan (China), and Mohammed Shawky Hassan (Egypt) talked about setting up and maintaining safe, queer festivals and/or spaces. Moderator Maxime Duvall raises the important question: how and where to start? Leyli Gafarova: “You need to look for an opportunity – I think there are always opportunities. It is about taking initiatives, and not being afraid of doing so. I mean, it is dangerous, but you somehow have to be naïve and crazy and start with an initiative and see where it takes you. There is no one way to do it, there is no universal recipe; in each country, it is different what the dangers are and how you have to approach it. The question is, do we necessarily have to recreate the same institutional ideas as in the West? We have to always remain critical of the protocols that we already know and listen to what the community in a certain place wants and needs.”

Masha Godovannaya explains how art can become activism: “The Side by Side festival started with the simple idea to just screen queer films, but it was politicized from the beginning onwards. We started having bomb threats. Homophobes will show up at the festival every time. You have to think about it; do we come to see a film or does it almost become a political act to be with the community?” Popo Fan: “I agree that the challenges are different in every country. In China, stereotypically, we don’t bother other people. So, people didn’t come to protest or hurt people at our festival, but we spend a lot of time trying to avoid being targeted by the authorities. Therefore, we have guerrilla tactics for showing movies; once, we showed a film on a riding bus.”

Exhibitions

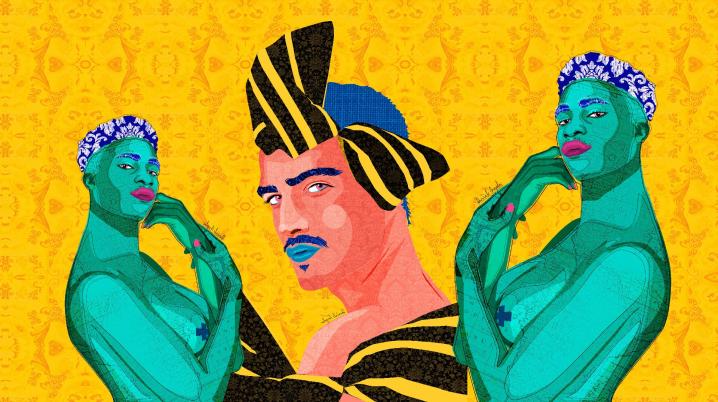

In between talks and film screenings, you can visit the exhibition spaces. Here, you can look at the amazing visuals by Daniel Arzola. Since 2016, he has illustrated the official artwork of IQMF. The walls are covered with colourful images of gender fluid and gender variant people. It is a rare pleasure to see gender non-conformity celebrated in such a beautiful way. If you have a careful look, you can see how the shapes of bodies and faces are created through collages of different structures – be they fabric, flower and butterfly patterns, or world maps.

In the exhibition space, you also have the opportunity to experience the love story of an Egyptian lesbian couple in an animated virtual reality (VR) documentary. This VR experience, titled Another Dream, is created by Tamara Shogaolu and attests to the power of storytelling through animations and the immersive experience that VR offers.

The other location of IQMF, Cinema of the Dam’d, is situated in a formerly squatted building. Cinema of the Dam’d hosts the other film screenings and exhibits the photography project Naked Berlin by Abdulsalam Ajaj and Mischa Badashyan. The images document interventions in Berlin by naked people who climb monuments or pose in parks. The images are beautiful and funny at the same time. "Have we really achieved the entire freedom of expression in public?" the photographs ask its viewer humorously, but also seriously.

Queer Artivism, the Moroccan Perspective

Next up is the film Salvation Army by Abdellah Taïa, followed by Sido Lansari’s short movie Les Derniers Paradis. The latter has an interesting form. The voice-over, accompanied by stop motion images and archive video material, recounts the story of Sami, a young man who ends up living in Paris. Lansari joins the panel discussion Queer Artivism, the Moroccan Perspective, where he explains that he wanted to tell a simple story in an original, new format. He tells us about the lack of stories about queer Arab people in France: “Queer people from the Arab region are considered ‘just Arab,’ not Arab ánd queer. I was looking at articles and stories about these people and I discovered that they were only written by French people. That’s why I decided to tell this story.”

In Salvation Army we follow the teenager Abdellah; we see how he watches television in a small room together with his mother and seven siblings, we witness his first homosexual encounters, and see how he eventually ends up staying at the Salvation Army in Geneva. Abdellah Taïa, director of the film and writer of the autobiographical novel that the film is an adaptation of (in 2007, the book was translated to Dutch titled Broederliefde), also joins the panel on Moroccan queer artivism. When he is asked if he considers the film an activist film, he replies: “Absolutely. Because now that I survived from those strategies of killing people like me, I can write and speak. And I am aware of the fact that our stories are not even written or shown. There is a huge lack of these stories told from inside. Every time when I see the film, I start crying because I can’t believe that I made it. Making a film is extremely hard; first of all, you have to write the screenplay and come up with a cinematographic idea that has layered meanings – I did not only want to write a gay story, from a Western perspective. For me it was extremely, extremely important to have a gay perspective and a queer perspective as a Moroccan perspective. Because there are gay Moroccan people like me. You also need to convince people endlessly to fund your film, and then if you get the money, you have to make sure people will not destroy your idea. For gay stories, there is already the gay narrative, no matter where the gay character comes from. They will try to push you to write the story they have in their minds. My challenge was to not let the expectations they had enter the screenplay.”

Food for thought

It seems that we can take away from both talks about the combination of art and activism in different regions that financial support is needed from countries like the Netherlands to support queer safe spaces and festivals. Financial support is also needed to tell LGBT stories taking place in non-Western regions that are created by its inhabitants, and to provide support for activist groups that are doing difficult and significant work. However, as the talks also highlight, it is important that we remain critical of interference and preconceived ideas of what LGBT activism and art should look like in other regions, since art and activist practices are situated. Additionally, we might consider how we can offer (queer) migrants better asylum procedures and safer spaces in the Netherlands.

By showing inspiring and provocative films and artworks, the International Queer and Migrant Film Festival provides a lot of food for thought. The festival affords much needed space and time to collectively reflect on different pressing issues concerning sexual diversity. As a result, the festival bolsters an awareness of LGBT issues and a solidarity that stretches beyond national borders.

DutchCulture is a partner of IQMF and co-organized the talks Queer Artivism, the Moroccan Perspective and Festivals for Freedom. On Sunday, the panel Safe Art Spaces: The Balkan Approach took place; read an interview with one of its participants here.