The story of the Erasmus Huis #3: 1970-present

In a series of three articles, we sketch the story of Erasmus Huis, the cultural centre of the Embassy of the Netherlands in Jakarta, in the context of cultural and diplomatic interactions between Indonesia and the Netherlands. This third and final article covers the development of the Erasmus Huis and its programming.

“Cultural relations between countries are of utmost importance. We need to understand each other’s culture", spoke the Director-General of Culture Haryati Subadio at the opening of the new Erasmus Huis building in 1981. Indeed, since its opening in 1970, the cultural centre had heralded a new era of strengthening bilateral relations between Indonesia and the Netherlands, in which cultural collaborations played a significant role. Its role evolved along political changes, shifting social trends and movements of supply and demand. As a Dutch cultural centre located in the ever-expanding mega-city of Jakarta, its position and programming within the local cultural scene have become unique.

From language to other arts

Within 10 years, the Erasmus Huis at Jalan Menteng Raya 25 was bursting at the seams. By 1981, it had about 3,000 members, 90% were Indonesian and 10% were Dutch. Of this 90%, half consisted of older people who learned Dutch during the colonial rule and the other half of younger people who didn't. Fewer and fewer Indonesians spoke Dutch. NRC Handelsblad warned in 1973 that “the position of the Dutch language is threatened: in twenty years Indonesia will only speak Indonesian”.

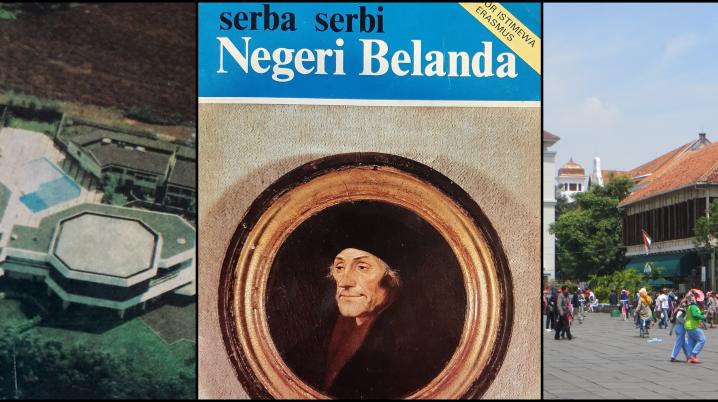

Consequently, the Erasmus Huis’ programming transformed from promoting the Dutch language to events in which language was less relevant, such as music, dance and visual arts. Most of the communication and part of the activities of the Erasmus Huis were therefore in Indonesian, such as the Embassy’s own magazine Serba-Serbi Negeri Belanda (‘This and that from the Netherlands’) which was published periodically in the period mid-1960s till the early 1990s. At the same time, the Dutch language courses were professionalized and expanded. The Erasmus Huis also took a more recreational role, even providing chess clubs and bridge evenings.

Accessibility to knowledge

The events held by the Erasmus Huis were well-received within Jakarta’s society. On 23 October 1971, the newspaper Kompas covered film screenings held at the Erasmus Huis for the first time. Since then, it published a frequent column titled Cultural Events in which the Erasmus Huis’ events were included: between 1971 and 1990 there are at least 300 mentions. Within a few years since its establishment, Erasmus Huis was considered one of the most prominent cultural centres in Indonesia in terms of accessibility to knowledge.

In 1976, Indonesian author and journalist Sides Sudyarto D.S. emphasized in Kompas that many young people encountered difficulties in pursuing their education because of the limited number of schools and universities, high tuition fees, and overpriced study books. Sudyarto pointed out that the Erasmus Huis, as well as the Goethe Institut, Yayasan Idayu (Idayu Foundation, now inactive), the French School of the Far East and several other institutes, provided free access to books and thus were a good alternative to freely access literary resources.

At the same time, the independence of cultural centres in Jakarta that were funded by foreign governments was questioned and there were doubts whether the use of such facilities would not silently reduce Indonesian nationalism. Responding to this, the ‘pope of Indonesian literature’, H.B. Jassin, commented in the same Kompas issue that “precisely because of our feelings of nationalism, we want to be able to understand the outside world better. By understanding the outside world, we will realize how big we are”. Jassin also dismissed common views that the Erasmus Huis was prejudiced towards Indonesia because of the Dutch colonial period and the Soviet Union’s Cultural Institute in Jakarta because of its relations with communism.

New, modern premises

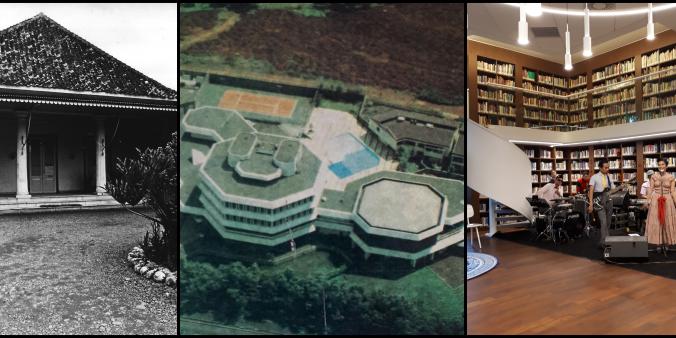

Both the Erasmus Huis and the Embassy building at Jalan Kebon Sirih 18 had become too outdated and cramped for the ever-expanding diplomatic team. The Netherlands' government eventually decided to relocate its diplomatic, consular and cultural functions to a new Embassy compound. In 1976, Governor Ali Sadikin of Jakarta offered a 1-hectare plot of land in the new southern suburb of Kuningan. After a tender period, the project was granted to PT Decoriënt Indonesia, a contractor based in Jakarta which was originally a Dutch-Indonesian company: Decoriënt is short for Dutch Engineering Oriënt. Recently, BAM International sold Decoriënt to its current management, ending a more than 50 years-period of Dutch-Indonesian collaboration.

The new compound was designed by Dutch architects Norbert Gawronski and Thijs Moll of architectural bureau Haskoning, in cooperation with Sangkuriang, an Indonesian company. The complex consisted of a “Consular department, a four-storey chancery and a two-storey ‘Erasmus house’, a Dutch cultural centre containing a library, classrooms, an exposition area and a multipurpose hall for 300 seats. Four houses for staff, a swimming pool, a technical building and a tennis court are situated at the rear”, according to a Decoriënt information sheet from the Erasmus Huis archive. The chancery and the Erasmus Huis both received distinctive octagonal shapes, and had a thoroughly modern, almost futurist design: a definite break from its previous colonial accommodation.

The opening of the new Erasmus Huis was performed by the Dutch junior minister of Foreign Affairs Durk van der Mei, who stated that “the Netherlands only rarely opens a cultural centre in this world as good as this one in Jakarta, which can only be matched with those in Paris and Rome, and which shows how important the cultural relationship with Indonesia is”.

Due to its new facilities, the Erasmus Huis could now host more and larger programmes, and for larger audiences. De Volkskrant mentioned in 1981 the exhibition Rembrandt and his contemporaries, music performances by Flairck and the Erasmus-ensemble, a conference by Henk van Ulsen and cabaret by d’Amateurs, as well as an educational conference for Indonesian Dutch-language teachers, a photo exhibition by Marie Bot and a performance by Dutch comedian Paul van Vliet. The 44th Serba-Serbi Negeri Belanda promoted the upcoming poetry festival Malam Puisi 81 Jakarta, with thirteen Indonesian and five Dutch poets, among which Remco Campert.

A criticised safe space

This poetry festival, which was held from 21 to 23 April 1981, is now ingrained in the memories of many progressive poets who grappled with power during the New Order era under Suharto. Kompas mentioned that at the festival, critical Indonesian poets such as W.S. Rendra, Sitor Situmorang (the first translator of Rob Nieuwenhuis’ critical book on Multatuli, Mitos dari Lebak, into Indonesian), Toeti Heraty, and many others were present.

Commenting on Rendra’s poem, which discussed the social and environmental impact of the government’s economic development in Indonesia, and which was greeted with raucous cheers by the audience on the second day, the newspaper wrote: “with his rhyme, he seemed to sum up the thoughts and feelings of many people”. Unfortunately, due to the language barrier, it also reported that the Dutch poets were not well received, and that “readers of the translations were engrossed as if they did not care about the interpretation of the poetry they read”. However, as Toeti Heraty recalled in Media Indonesia in 2015, the Malam Puisi 81 Jakarta festival succeeded in presenting “many poets who had not been active for a long time” due to the political climate.

Even though the Erasmus Huis had offered a safe space for interaction and cultural exchanges, there was still criticism of its service. In 1983, Kompas published a reader’s letter from a user of the Erasmus Huis library called Tubagus Budi Rachman. His contribution started with the jarring title “In the Erasmus Huis, there is discrimination [based on] skin colour”. He wrote that an officer at the Erasmus Huis had reprimanded him and several other Indonesian users for bringing bags into the library, while the warning was not given to “white women (Dutch people)” present.

Six days later, the complaint was answered in the same newspaper through a statement of regret written by Erasmus Huis director Roel Verstrijden. According to Verstrijden, this was the first complaint since the founding of Erasmus Huis in 1970. The quick action by the director of the Erasmus Huis was highly necessary because the complaints evoked experiences of discrimination endured by many during the Dutch colonial period.

Sit in the loge for a dime

Initially many of the Dutch performers at the Erasmus Huis were subsidized by the Dutch government. Indeed, the Erasmus Huis was intended to (re)present the Netherlands as a country and Dutch culture and language specifically to Indonesian audiences. The 1989 Note Dutch cultural institutes abroad stated that “the promotional effect of these activities is the translation of general interest in the Netherlands into a concrete specific interest in any field, including trade, industry and tourism”. Subsidies for culture could pave the way for more lucrative counterinvestments, so to say.

However, the impact of the Erasmus Huis should also be understood in contributing to the mutual understanding between the Netherlands and Indonesia, specifically considering the historical and cultural ties between both countries. Due to heavy budget cuts by the Dutch government during the 1980s, the Erasmus Huis and its mission could depend less on subsidies and had to find alternative sources of income. These were found in renting out its facilities for different events and activities organized by external organizations, both Indonesian and foreign. “Dutch cultural policy does not mean much”, the Algemeen Dagblad wrote in 1988, referring to the Erasmus Huis, “the less public money is put into it, the happier our government is. The private initiative is amply welcomed so that the Netherlands can sit in the loge for a dime”.

Creative transformation

Despite the declining government funding for its activities, the Erasmus Huis kept on adapting its programming to stay relevant within Jakarta’s society. In the 1970s, Kompas reported that the Erasmus Huis was a venue for film screening, wayang performances and paintings exhibitions. In the 1980s, especially after having moved to the Kuningan area, it reported that the Dutch cultural centre held photo exhibitions, symposiums on ageing, Christmas concerts, seminars on the translation of Dutch colonial legal documents, and exhibitions on old coins used in Indonesia.

More recently, Suni Wijogawati, a retired project manager of the Erasmus Huis who was interviewed for this article, explained the extent to which the programming changed over time. “At first we only focused on classical music and culture, but now we are also exploring pop music”, she said. Technician Gideon Sapulete added that they are also programming very popular electronic dance music. Besides, at Erasmus Huis unusual places can be creatively turned into event venues. Rina Tjokorde, the also recently retired Erasmus Huis librarian who served for more than three decades, said that the library was occasionally turned into a concert venue.

A mature relationship

In 1988, newspaper Het Parool wrote in a tiny article on the front page of 23 February that “in Jakarta, there is a wave of nostalgia for the time when the Netherlands held sway there”. It based this remarkable observation on a slightly more elaborate New York Times article which described that “Dutch language courses at Erasmus House are full; Dutch colonial buildings are being restored, including the old City Theatre, built when Jakarta was Batavia. Restaurants, and one exclusive club frankly evoking the colonial era, are opening”. It continues with quoting an Indonesian NGO worker who explained that “Indonesians (…) know themselves and are proud of their history, cultures and institutions” while “artists and writers (…) say the Dutch period disrupted the traditional arts minimally if at all. More often, Europeans took inspiration from the developed civilizations of Java, Bali and other islands”.

Both the New York Times and Het Parool included quotes by Dirk R. Hasselman, a counsellor at the Netherlands Embassy who was also stationed in Jakarta in the early 1970s: “Indonesia’s relationship with the former colonial power has matured (…) What we experience now would have been inconceivable back then”. This trend has continued. More recently, the Jakarta Globe visited four high-end restaurants located within Dutch colonial buildings, reminiscing that “Jakarta is one of those cities that have exceptionally rich colonial architecture. While hundreds of its historical buildings, especially in the Kota Tua complex, still require restoration, many have recently been turned into public spaces”. Such a change was especially remarkable considering that in the early 1960s, bilateral relations between the two countries were completely severed.

50th anniversary

To the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Republic of Indonesia in 1995, the same year in which Queen Beatrix, Prince Claus and Crown Prince Willem-Alexander ventured to Indonesia for a state visit, several Dutch private companies with interests in Indonesia funded the restoration of the colonial Reinier de Klerk Huis on Jalan Gajah Madah. This former estate of one of Batavia’s Governors-General was meticulously restored and transformed into the new main offices of the National Archives of Indonesia, as well as a wedding venue. The project was guided by Indonesian and Dutch restoration architects, and the contractor was the previously mentioned PT Decoriënt Indonesia. The transformation won the Award of Excellence at the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation in 2001.

The Netherlands Embassy and the Erasmus Huis also supported their fair share of heritage projects. Some examples are the workshop Documenting Architectural Heritage in Jakarta of Ikatan Arsitek Indonesia (Indonesian Architects Association) and its Dutch counterpart Bond van Nederlandse Architecten (Association of Dutch Architects) in 2003; the documentation of Gedung AA Maramis (Ministry of Finance, formerly Daendels’ Palace) in 2004-2005 and 2011-2012; hosting the exhibition Tension, 100 years architectural perspectives in Indonesia at Erasmus Huis in 2007; the inventory of forts throughout Indonesia in 2007-2010; or the documentation of the Museum Sejarah Jakarta (Jakarta History Museum, formerly Batavia’s city hall) in 2011.

Heritage and international cultural policy

The Reformasi era, the period after President Suharto’s resignation in 1998, witnessed increasing heritage conservation collaborations between the Netherlands and Indonesia performed by private restoration architects, educational institutes and government agencies. From 1997 onwards, heritage became embedded in the Dutch international cultural policy, aiming at strengthening bilateral relations between the Netherlands and countries with which it has a shared, not exclusively colonial, history. Indonesia was of course one of these countries, and as the Netherlands’ cultural representation in Jakarta, the Erasmus Huis played a key role in the implementation of this policy.

Initially, between 1997 and 1999, the term ‘Dutch cultural heritage overseas’ was used for this specific type of heritage which “the Netherlands, especially during the time of the Dutch East India Company and the West India Company, left behind in the world in the form of monuments, buildings, archives and shipwrecks”. With this policy “a strong emphasis is placed on finding common ground for supporting activities and raising awareness on the ground of the importance of this area. The policy, therefore, focuses mainly on those countries where the Dutch presence has had a more lasting significance for the local population and is seen as a cultural achievement of its own”.

The term ‘overseas’ had certain colonial connotations. The responsible Ministries of Foreign Affairs and of Education, Culture and Science apparently thought so as well, as they consecutively changed the term from ‘mutual cultural heritage and heritage overseas’, to ‘mutual cultural heritage’, ‘mutual heritage’ and ‘common cultural heritage’ between 2000 and 2012, to ‘shared cultural heritage’ from 2013 to 2020. The term was yet again updated to ‘international heritage cooperation’ for the latest version of the International Cultural Policy in 2021.

Fierce public debates

The public debates in the Netherlands on its colonial history and its impact on countries around the world have been growing fiercer in the past few years. They give an interesting new layer to the existing heritage collaborations between the two countries. In the Netherlands, there is a particular focus on the Dutch role in the Indonesian War of Independence. In 2017 the national government commissioned three Dutch institutes for the research programme Independence, Decolonization, Violence and War in Indonesia, 1945-1950, which particularly “looks into the nature, causes and impact of the Dutch acts of violence” in this period.

During the state visit of March 2020, King Willem-Alexander, flanked by Queen Máxima and Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo at Bogor Palace, addressed the war, stating: “I would like to express my regret and apologize for excessive violence on the part of the Dutch in those years. I do so in the full realization that the pain and sorrow of the families affected continue to be felt today”. And in May 2020 feature film De Oost (The East) premiered in Amsterdam, covering the perspective of Dutch boys who voluntarily enlisted to fight in an attempt to regain control over the Indonesian colonies, and the different choices they made in the process. A spin off of this film was used for an educational programme for Dutch high school students to learn to get a multi-perspective insight into the Indonesian War of Independence.

In February 2022 the results from the aforementioned research programme were published. Because of its main conclusion, that the Dutch army systematically used extreme violence during the Indonesian War of Independence, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologized to the Indonesian people.

Mutual projects and co-creation

Within this dynamic context, the Erasmus Huis, as well as its cultural partners in both the Netherlands and Indonesia, has been steadily adapting its programming and function as a cultural platform for conversation. In its over 50 years of presence in the Jakartan cultural scene, it has become a well-known brand and popular venue with particularly young Indonesians. The Erasmus Huis has supported projects addressing the shared and contested history of both countries, such as photography projects Heritage in Transition and I Love Banda by Isabelle Boon, Suzanne Liem’s photography project The Widows of Rawagede, the multidisciplinary co-creation My story, shared history between Indonesian and Indo-Dutch artists, the exhibition Segar Bugar: The story of conservation in Jakarta 1920s till present and the book presentation of the Indonesian translation of Didi Michielsen’s novel Lichter dan ik (Lebih Putih Dariku).

Occasionally the Erasmus Huis also programmed activities in Kota Tua, the historical inner city of Jakarta. At the same time, its more traditional programming such as music, theatre, performances, as well as its library function have been consistent. Apart from providing a stage for Dutch singers, bands and DJs in their own premises, or organizing and managing their tours through Java, Bali, Sulawesi and Sumatra, the Erasmus Huis increasingly invites Dutch and Indonesian artists to perform and create new material together. Recent names on the bill include the Junior Company of the Dutch National Ballet (who trained together with the Namarina Dance Company from Jakarta), jazz singer Sanne Rambags, who performed with a gamelan orchestra and wayang master Wayang Gamblang Nusantara and Dalang Ki Gamblang, workshops by rock band Altın Gün who also performed with El-Farhan, an Indonesian gambus band, and the screening of Dutch children movies with Indonesian subtitles.

Collaborations with other European cultural institutes in Jakarta have been found in the annual Europe on Screen Film Festival. Gradually, the Erasmus Huis is broadening its cultural collaborations to other cultural disciplines such as film, creative industry and design. Building With Nature is a recent example in which Dutch and Indonesian designers worked together on an exhibition on sustainable materials. It actively seeks collaboration with Indonesian festivals, like Solo Perfoming Arts Festival and Jakarta International Photo Festival as well as with art academies throughout the archipelago. Also, the centre seeks to utilize its facilities and name to programme other, Embassy-wide topics such as human rights, climate change and LGBTQ+ rights.

Remaining relevant

Throughout the past decades, the Erasmus Huis has continuously adapted its programming, firmly established its position within the Jakartan cultural scene, offered a stage for Dutch and Indonesian artists, as well as strengthened its role as a centre for cultural diplomacy for the Netherlands Embassy in Indonesia. As such, it has always remained relevant through different governments, both Indonesian and Dutch, and within the ever-changing dynamics of the relationship between former colony and former colonizer.

The story of the Erasmus Huis #1: 1945-1960

The story of the Erasmus Huis #2: 1960-1971

This article has also been published in Indonesian on Historia.id. You can find this article here.

Special thanks to the research assistants of this project, three Bachelor students from Universitas Indonesia: Harry Farinuddin (History), Muhammad Gibran Humam Fadlurrahman (History) and Sarah Ardelia Saptono (Dutch Studies)