Art and Migration: on cultural internationalisation in the age of displacement

Researcher Errol Boon wrote a personal essay on DutchCulture’s colloquium on the aesthetics of displacement and Gianfranco Rosi’s film Fuocoammare, both programmed during the Forum on European Culture. The colloquium was part of DutchCulture’s research project on cultural internationalisation in a globalised world (see for related items below).

Artistic internationalisation in the age of displacement

‘’The island of Lampedusa has a surface area of 20 square km; it lies 113 km from the African coast and 205 km from Sicily. In the past 20 years, 400,000 migrants have landed on Lampedusa. In the attempt to cross the Strait of Sicily to reach Europe it is estimated that 15,000 people have died.’’

These simple yet brute facts form the opening scene of Gianfranco Rosi’s award-winning documentary Fuocoammare (‘Fire at sea’). One month after the film’s release in February 2016, the notorious migration deal between the European Union and Turkey came into effect. Under this agreement, the EU paid Turkey six billion euros to stop migrants from crossing the European border. In addition to Turkey, the EU had already funded the Libyan authorities (infamous for their torture methods in migrant detention centres) and even the Sudanese militia Janjaweed (infamous for their genocide in 2004-2007) to stop migrants from coming to Europe (see Baldo 2017; Barbieri 2020). The New Pact on Migration and Asylum, presented September 23 by the European Commission, is a continuation of this policy that is primarily aimed at reducing the incoming migration flows – a forlorn policy in which neither the protection of human rights nor the promotion of humanist values is guaranteed (see e.g. Amnesty International 2018, Human Rights Watch 2019).

The EU’s attempt to do almost whatever it takes to control immigration numbers is due to EU's painful inability to reach an urgently needed unified interior migration policy, especially regarding the equal spreading of migrants across the member countries. This absence of a unified policy becomes all the more pressing as the urgency for such a policy increases. However, as long as the national governments of some member states (notably Poland and Hungary) block any possibility for cooperation, and as long as the dominant political debate is hijacked by the xenophobia and nationalism, integral European solidarity remains a lost cause. Meanwhile, the situation is bursting at the seams, as demonstrated by the burned refugee camps on Lesbos; so in order to at least do something (or, arguably, in order to reduce the pressure to do something), the EU focuses on enforcing border controls and expediting deportation procedures. Paradoxically, this policy is a genuflection to the nationalist and xenophobic discourse that is blocking a pan-European migration policy in the very first place. Hence, European migration politics is literally stuck in a mode of thinking that offers no perspective on a European solution for the humanitarian crisis happening at its borders. Our discourse about migration needs to be liberated.

As an alternative to this discourse in which European migration politics seem to be caught up, artists and cultural workers, especially those working interculturally, have sought to critically respond to the migration crisis in a different, aesthetic manner. At the recent Forum on European Culture, organised by DutchCulture and De Balie, various of these aesthetic responses were presented, including Rosi’s Fuocoammare, Fernando Sánchez Castillo’s Figures of freedom, the photographic exhibition Afropean by photographer Johny Pitts, and Charl Landvreud’s performance The Utopia of the Normal Space. These works of art offer an aesthetic approach to migration that disrupts the expectations and anticipations that are conditioned by dominant discourses. Take Rosi’s Fuocoammare, for example: after seeing the numbers at the beginning of the film (quoted above), the viewer naturally expects to see images of boat migrants and suffering refugees - images that are as horrific as they are familiar to us from the daily news. Instead, however, the scene succeeding the text-opening consists of long silent shots in which we see a young boy from Lampedusa, Samuele Pucillo, playing outdoors in the island’s beautiful nature, manufacturing a catapult and trying to shoot birds with a friend. As one watches the film, one encounters a documentary about Lampedusa that not only portrays migrants, but mostly the lives of people like Samuele and his grandmother, the DJ of the local radio station, and the doctor of Lampedusa. Given that Fuocoammare is a documentary about the migration crisis in Lampedusa, as the quoted opening facts inevitably imply, it raises the question why Rosi chose to feature all these lives in his critical aesthetic approach of the subject matter. What is the critical potential of an aesthetic approach to such an overly discussed topic as migration? Can works of art provide a fruitful alternative mode of thinking, besides the forlorn discourse in which European democracy has become entangled?

Artistic internationalisation in a globalised world

The question how artists and cultural workers can critically relate to the effects of globalisation, such as the current migration crisis, gains added significance in the context of what is often called the increasing internationalisation of the arts. At present, almost all cultural activities in Europe – the international programmes of our theatres and cinemas, the translated books in our libraries, the students of our conservatoria and art schools and so on – are in one or other way involved with or affected by international collaborations between artists and cultural workers from different parts of the world.

For centuries, the intrinsic value of this cultural internationalisation was unquestioned. The belief that artistic practices should never be limited by contingent national borders led to the idea that cultural exchange between artists and audiences from different countries had the potential to fundamentally broaden our mind. This ‘cosmopolitan ideal’ became the ethical justification and ideal motivation for the increasing cultural internationalisation (see Boon 2020b). As historian Orlando Figes noted in a conversation with Joost de Vries at this year’s Forum on European Culture, it was especially in the 19th century that artists and intellectuals came to believe that the artistic transfers, translations and exchanges among countries could strengthen international fraternity and solidarity by either creating or reaffirming existing commonalities between people from different (European) cultures (Figes 2019).

This ethical justification of cultural internationalisation lives on in most European countries today, where governments invest a considerable share of their cultural budgets in stimulating the internationalisation of their arts sectors. We continue to believe that the arts can enrich us with foreign and unfamiliar perspectives that confront us with the contingency and ambiguity of our own values. In showing foreign films and documentaries to children, creating international exhibitions in museums, translating books from various parts of the world and stimulating artists and cultural workers to engage in residencies, collaborations and tours abroad, the tacit cosmopolitan assumption is that intercultural exchange is the best education for global citizenship (cf. Appiah 2008).

However, this idealistic 19th-century justification of cultural internationalisation no longer applies in the same way in our current globalised world. After all, a world where even the remotest places are connected with each other and where a single bat sold at a local Chinese market can cause a global pandemic – such a world is already an internationalised world (Boon 2020a). That means that in our globalised world, internationalisation is no longer an ideality to strife for, but rather an inevitable reality that confronts cultural workers with complex moral and artistic challenges (cf. Janssens 2018). Although globalisation carried the promise of realising the cosmopolite ideal, one could argue that globalisation has instead problematised the cosmopolitan ideal of global solidarity, intercultural exchange and artistic self-development.

This disenchantment of globalisation, which increasingly characterises the consciousness of our age, urges also artists and cultural workers to reformulate the justifications for their international work (see Boon 2019). For instance, how can ‘intercultural enrichment’ or ‘diversification of audience’ still be valid reasons to go abroad, when a subway ticket to a suburb often gives access to a more diverse audience than a flight ticket to another gentrified city centre at the other side of the globe (see e.g. Van Imschoot 2018)? How can intercultural artistic work bring people closer together if every international collaboration takes place in a world that is always already structured by global power differences that are very likely to be reproduced in artistic collaborations (cf. De Graan 2018; Bul 2019)? Do I allow myself to travel by plane in a world that is being destroyed ecologically by our globalised economy (cf. Kyle 2019)? As an artist working abroad, one is inevitably confronted with questions arising from globalisation’s broken promises.

There is one broken promise of globalisation that is especially relevant for our question of art and migration; namely, that the diminishing of strict national borders has in many respects not led to the international solidarity that was expected to follow from international collaboration. Instead, the dominant response to the fading of national sovereignty currently appears to be a revival of a discourse of nationalism, protectionism, xenophobia and other forms of resentful politics (cf. Hall 1997). The old cosmopolitan ideal that internationalisation would lead to international solidarity, and thus that artistic international projects foster mutual understanding and empathy, has therefore lost its self-evidence.

What we see today is, on the one hand, that modern-day political resentment is very much directed against the internationalisation our life world. Yet on the other hand, most artists and intellectuals still see the active, expressive and imaginative power of art to be the most promising antidote to prevent political disappointment from turning into resentment. Artists and cultural workers are thus challenged to find out how international cultural activities can potentially disrupt rather than fuel the dominant political discourses. If we want to revitalise the cosmopolitan justification of artistic internationalisation and demonstrate that intercultural exchange can contribute to mutual understanding and democratic solidarity, we need to explain how art can disrupt the very logic of the discourses that presently hinder such understanding. If there is a cosmopolitan value in art, it must lie in its potential to liberate us from dominant modes of thought.

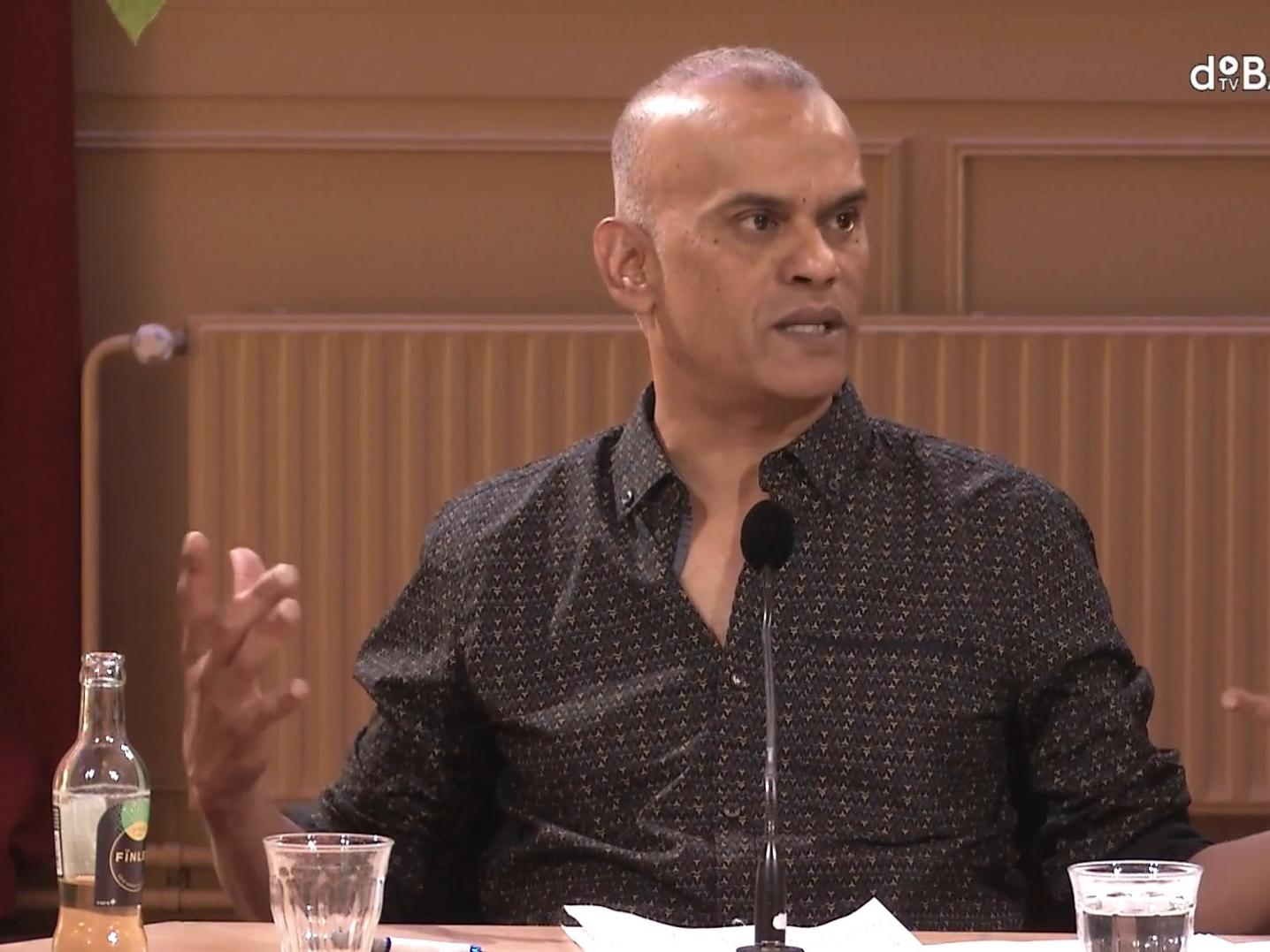

Sudeep Dasgupta and the aesthetics of displacement

During the Forum on European Culture, DutchCulture organised a colloquium on aesthetics in the age of displacement with Sudeep Dasgupta, Associate Professor of Media and Culture at the University of Amsterdam. Building on his articles ‘Fuocoammare and the aesthetic rendition of the relational experience of migration’ (Dasgupta 2019b) and ‘The aesthetics of displacement: dissonance and dissensus in Adorno and Rancière’ (Dasgupta 2019a), Dasgupta explored the potentiality of aesthetic experience to disrupt and destabilise dominant political discourses.

Dasgupta begins his argument with the premise that migration inevitably challenges our existing political, intellectual and social understandings of the contemporary global order. According to Dasgupta, the current political discourse in Europe has become problematic because it ignores rather than recognises these challenges. Instead of understanding the world as a relational space with entangled common histories, transforming societies and evolving cultures, the dominant discriminatory discourse offers stable map of an inter-national world that is divided into clear-cut territories and isolated cultures, separated by identifiable borders. Understood from this straightforwardly communicable understanding of cultures and civilizations, migrants are outsiders trespassing clear boundaries. In order to prevent European societies from a war of civilizations, religious conflicts and an economic drain as a result of ‘them’ invading ‘our’ societies, it is easy and even logical to argue for solutions based on reinforcing borders and marking out clear territorial separations, for instance by means of walls and border controls.

However, the reality of migration thwarts this simplistic separatist world picture; migrants undermine the very idea of globalisation as inter-nationalisation. Rather than fleeing from one nation to the other, trespassing territorial borders, a migrant should be seen as a translocal subject (cf. Smith 2011). The space that the migrant crosses is not primarily marked by topography, but by danger and safety, shrivel and prospect, risk and opportunity. In this sense, the migrant forces us to recognise how the global and local are intertwined and how the world manifests itself in our local environments, while the significance of the nation state is increasingly relegated to the background (cf. Vanackere 2019). Thus, Dasgupta argues that the presence of migrants represents an evolving rather than static understanding of cultures, entangled rather separated histories.

But why does Dasgupta find it relevant to talk about aesthetics in this context of displacement and globalisation politics? What does ‘aesthetics’ actually mean? Stemming from the Greek aísthēsis, ‘sensory perception’, aesthetics is certainly not confined to a theory of beauty or art. ‘Aesthetics’ rather designates the whole sensory order one experiences through the bodily senses – ranging from our daily experience of a city’s layout, the flavours of food in restaurants, the sounds produced by our mobile phones, the scent of freshly mown grass. In short, the aesthetic marks our experience in so far as it is a bodily experience before being a conceptual reflection. And that position in between sensing the world and making sense of it makes the aesthetic experience politically significant. For this process of conceptualisation - this passage from how we sense the world to how we know the world – always involves a filtering of the overwhelming amount of sensorial input. That is, in order to come to a conceptual understanding of the sensorial material, I inevitably exclude certain particularities and concentrate on others, so that there is always sense data that is left out in the process of shaping meaning and interpreting the world. And this is where aesthetics becomes the arena of politics; because, why do we do we select certain sensorial material over other sense data? Which aspects of our sensory experience are we expected to find important and who decides that? According to Dasgupta, this sensorial selection process is a political process par excellence, and therefore aesthetics has political relevance.

Since the aesthetic experience is sensorial before it is conceptual, it has the potential to interrupt the very process of conceptualisation: by standing between sensing the world and knowing the world, it can call into question our very capacity to know and to conceptualise the world. Hence, through it aesthetic experience art has the potential to destabilise dominant ways of explaining the world and can introduce doubt when political discourses claim self-evidence. In other words, rather than offering new narratives or moral statements, art’s critical power might lie especially in its ability to disrupt the defining and reductive operations of our conceptual thinking itself, no matter what its content might be.

One way in which art can do so is by refusing to use images as mere illustrations with which to offer simplistic explanations of the complex contemporary world. Photography and cinema, for example, can confront us with images that do not fit within the dominant discourses, as a result of which the viewer needs to explain these images by herself without drawing on dominant conceptual frameworks. An image that refuses to fit a general story or a rational argument might be the most subversive aesthetic experience possible, since it liberates the image from the expectation of telling a story or representing a situation.

As Dasgupta wants to demonstrate, art’s potential disruption of reductionist discourse applies especially to the dominant separatist discourse that occupies European migration politics. Dasgupta believes that by interrupting and interrogating the clear-cut divisions of space that these political discourses seek to communicate, art can alter ‘fixed meanings ascribed to space and open it to bodies, realities and histories that are entangled together through processes of displacement’. Thus, Dasgupta explains how art can call into question the legitimacy of existing social orders in which everyone is assigned their proper place, by bringing to the surface particularities and entangled histories that do not fit that dominant social order. In this sense, aesthetics can indeed reframe the world, redrawing the coordinates of internationalisation – creating an experience of ‘traveling’ in the sense of genuinely encountering foreignness, rather than only recognising the expected, clearly articulated stories and discourses.

Fuocoammare

In order to understand the power of aesthetic experience to disrupt dominant discourses on migration, it is illuminating to look at the aforementioned documentary Fuocoammare as an example of how this critical potential can be realised. Rosi’s documentary is an interesting example, because it is, on the one hand, an international work of art in the strict sense of the word: it features the lives of both Italians and of migrants from various nations in Africa. At the same time, however, this inter-nationalist logic that divides the world into distinct nation states, inhabited by citizens and trespassed by migrants, is precisely what is undermined in Rosi’s film. Furthermore, one could say that Fuocoammare is a translocal work of art par excellence (cf. Doorman 2020), both in the sense that it deals with displaced, stateless people who are primarily seeking a safe locality rather than crossing national borders, as well as in the sense that the film investigates a local environment – roughly the 20 square km of Lampedusa – as a juncture of worldwide movements.

To understand how Fuocoammare undermines dominant modes of explaining the world, Dasgupta recounts how he came to hear about Rosi's documentary: ‘When I heard about Fuocoammare and read about it in the newspapers, I heard it was a documentary and that it was about migrants; moreover, the word ‘Lampedusa’ fell. Well, all these notions immediately raise assumptions, expectations, pre-conceptions, so that, when watching the film, I naturally expected to see the experience of migrants, their processes, images of boat refugees, stories of death, etc.’ According to Dasgupta, Rosi’s film is an example of an artwork where precisely these sorts of general assumptions are thwarted - where ‘we lose our way just at the moment when we thought we knew’ – and hence where the individual’s own critical and imaginative abilities are activated.

As described above, one’s expectations are already disrupted in the very beginning of the film, when the images succeeding the opening text do not form an explanatory or narrative link with the opening facts. In fact, the whole film consists of a sequence of images from Lampedusa that are not causally linked to each other as different elements of one narrative or argument. The images of migrants are connected with, for instance, pictures of Samuele learning English at school or of an old man catching sea urchins, without relating these images causally to construct a clear, linear plot about the migrants. In fact, apart from the opening facts, there is no voice-over or accompanying text to explain the connections between the scenes.

According to Dasgupta, the film does not seek to explain anything by itself: the images are not meant to illustrate an idea, to represent an explanation or furnish a description of the situation of the migrants. Rather, through this non-causal sequence of images, the viewer is left with the task of understanding the images without reducing them to a general story or argument: since the gaps between the images thwart our expectations, we are forced to establish links by ourselves. That is, one can only make sense of this cinematic experience by contemplating and interrogating the actual images without relying on dominant discourses of explaining the world.

Since migrants are not used here to explain or illustrate a general argument, Dasgupta argues that the bodies of the migrants transform from being merely objects of our knowledge and representatives of either a cultural threat or humanitarian crisis, to being subjects worth seeing and listening to. By not being pushed into a motivated, causal sequence, the pictures of the various figures in the film co-exist rather than building upon each other linearly. Instead of representing the space of Lampedusa through a one-dimensional meaning or narrative, Dasgupta argues that Lampedusa thus becomes a ‘relational space’ in Rosi’s film: a place of co-presence where diverse individuals, intertwined stories, entangled histories, separate fragments and an array of images cohabitate. As a result, the name ‘Lampedusa’ – that normally overdetermined symbol of threat and crisis, that place that demarcates ‘us’ from ‘them’ - is now liberated from its fixed identities and becomes a location for the lives of all at the same time. Dasgupta thus concludes: ‘the politics of the film resides in helping us to rethink Lampedusa as a space of a counter-intuitive copresence, (..) to rethink the relations between different people whose pasts and futures intersect in a cohabited present.’

Art as truth claim or moral call?

During DutchCulture’s colloquium on aesthetics in the age of displacement, various critical questions were raised following Dasgupta’s lecture. Most of these questions addressed the possibility of the proposed amoral and non-discursive critique proposed by Dasgupta, i.e. the idea that visual arts can be critical without evoking an articulated moral argument or narrative, solely by disrupting dominant discourse formation of any sort.

The non-discursive or ‘muted’ character of Fuocoammare was questioned by Katia Hay Rodgers, Assistant Professor in Philosophy of Art and Culture at the University of Amsterdam. Whereas Dasgupta highlighted the absence of voice-over and the scarcity of text and dialogue in Fuocoammare as a way of interrupting discursive expectations, Hay Rodgers points out that the film actually does capture some moments of text and dialogue. In fact, the film’s silence, which Dasgupta highlights in his argument, makes these spare moments of discourse all the more important, according to Hay Rodgers. In reading the film, as well as in analysing its critical potential, we must explain the power that these words might have: there are not just images that disrupt discursive expectations, but there are also words suggesting how to read the images. And what is more, according to Hay Rodgers, it is inevitable that we continue to read the images within a certain discursive context of articulated thoughts, reasoning and a minimal understanding of the present political situation. If the critical potential of a visual work of art, such as Fuocoammare, continues to depend on discursive reason, it remains unclear how art is able to disrupt dominant modes of explaining the world and thus transform our experience and understanding of global migration.

Dasgupta explained the politics of the film as a ‘non-pedagogic truth claim’: the depiction of the various unconnected figures show us the co-presence of people – which is a truth that dominant separatist discourses seek to undermine. Hay Rodgers, however, interprets the depiction of the highly diverse figures on the small island of Lampedusa as a critique on the alienation of the European people from refugees and migrants; a critique that inevitably contains value judgements or articulated moral standpoints: ‘I see the film not as a truth claim, but as a call – a call that there is fire at sea, and that this happening right now, in front of all of us.’

Similarly to Hay Rodgers, dramaturg and curator Lara Staal questioned whether a non-causal relational aesthetics, which Dasgupta reads in Fuocoammare, would actually be able to change our understanding of the world. Although Staal agrees that Fuocoammare thwarts the linear forms of storytelling that reinforce existing power relations, she wonders whether a disruption of dominant narratives alone is enough to counter xenophobic politics. In today’s world, where Staal sees a renewed desire for one single overarching narrative, we might need a strong counternarrative instead of images that disrupt storytelling. ‘Wouldn’t it be much more effective’, Staal asked, ‘if the arts try to realise their critical power within an alternative power structure, one in which values like empathy, identification and dependency are explicitly advocated?’ Whereas Dasgupta sees Fuocoammare as undermining discourses that construct power structures, Staal thus suggests that the arts must necessarily subscribe to a power structure in order to criticise another; therefore we should not criticise the ‘bad’ stories by disrupting storytelling, but rather by telling different stories.

Finally, Annick Schramme, Professor in International Cultural Policy at the University of Antwerp, offered a different view on the societal relevance of artistic encounters, which is more in line with the alternative presented by Staal. Contrary to Dasgupta’s view on the aesthetic as the realm where the sensorial and the rational interrupt each other, Schramme instead sees aesthetics as a ‘non-confrontational means of complementarity or revelation’. As an example she refers to her research on post-apartheid arts and culture in South Africa, where she found that people understand art and culture as ‘a way of healing’, ‘the glue of society’. Instead of seeing art as a place for dispute or contention between the sensorial and the conceptual, in Schramme’s view art realises its critical potential by creating a place where the sensorial and rational can mutually enrich and complement each other.

To conclude: the politics of indifference

As an example of the reductionist and oppressive operations of our conceptual discourse, Dasgupta mentioned the application procedures pertaining to sexual asylum. The testimonies of the sexual asylum seekers often do not match the strict categories and protocols of the European immigration services, as when, for instance, the particular life-story of a refugee might not fit our logic of lesbian identity. One week after Dasgupta’s lecture, this oppression of general categories on particular experiences was again reinforced in the EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum. The European Commission’s ‘fresh start on migration’ plans to put newly arrived migrants through a quick first application procedure of maximum five days in order to determine whether the migrants have any chance at all of receiving a refugee status in Europe. Since such a quick procedure will be based on one’s country of origin and not on one’s personal story, the fundamental right of migrants to have their individual history is violated. This right to be heard personally is a crucial migrant’s right, since a country of origin that is a safe country for one might not be a safe place at all for another (cf. Polman 2020). Within this conflict between, on the one hand, the general discourse of concepts, categories, procedures and expectations, and, on the other hand, the particular sensorial reality of individuals, art potentially has a political and emancipatory role to fulfil. For art can emancipate precisely the singularity that cannot be understood through general concepts, the atonal note that does not fit the whole; art can highlight the particular and sensorial reality that is normally lost in our conceptualised understanding of migration, such as a refugee’s experience that does not match up with Europe’s procedural system.

With the remarks by Hay Rodgers, Staal and Schramme, the question becomes whether art should express an articulated political position in order to be politically relevant. For Dasgupta, the emancipation of the singular experience can function as a critique of general structures without formulating an explicit political argument or narrative. In his response to the participants of the colloquium, Dasgupta admitted that he does see the aesthetic strategies of Fuocoammare as modes to come to an argument. That is, the aesthetic experience does not exclude knowledge or meaning-making; the film is not about nothing, there is a certain political point to be made. However, the responsibility of articulating the argument at stake resides in the viewer – and that viewer can thus also refuse to make that argument or perhaps overlook the possibility of making the argument.

At the core of Dasgupta’s view lies a reluctance to reduce art’s critical potential to that of telling a discursive or moral counter-story. Such a ‘pedagogic’ understanding of art naturally runs the risk of being moralistic and ineffective in convincing people that do not share the same moral outline in the first place. Indeed, whereas articulated moral arguments also occur in discursive contexts, such as academia, journalism or daily conversations between people, the idiosyncratically aesthetic critique that only art can potentially deliver against the political discourses around migration might exist in the peculiar disruption of conceptual discourse, rather in presenting an articulated moral argument. That is why Dasgupta calls Fuocoammare a truth claim: the relationality depicted in the film is not a moral appeal that we should ‘be nice to each other’ or that it is ‘good’ to live together; instead, the film is saying: this is the reality, and political discourses that shut their eyes to this reality are actually false.

According to Dasgupta, Fuocoammare is not a moral statement but a political one. Its truth claim is, of course, not a neutral description – as he says, ‘it will actually function as a call, a political interruption’ - but its provocative and disturbing effect on us is not pedagogic or moralistic. Dasgupta calls this non-pedagogic concern the ‘politics of indifference’- a form of politics that acknowledges the presence of differences but cannot be sure of the meaning of that difference. Rosi’s film testifies to this politics of indifference, for it acknowledges the copresence of difference without fixing, identifying, classifying or explaining these.

Rather than calling for empathy and solidarity, a politics of indifference might be a productive way in which the arts can critically relate to Europe’s forlorn discourse on migration. And this sheds new light on the problem with which we started, namely that globalisation has not led to international solidarity, which has problematised the cosmopolitan justification of cultural internationalisation. In an attempt to revitalise the cosmopolitan legitimisation of mutual understanding and international fraternity, artists and cultural workers may explicitly make a case for values like empathy and solidarity. This is, of course, a possibility and often very noble. However, such critical strategies also run the risk of reproducing, at some level, the logic and discourse in which Europe has become entangled. That is neither necessarily problematic (as Staal pointed out), nor does it seem to be fully surmountable (as Hay Rodgers pointed out), but works such as Fuocoammare demonstrate another artistic option that is less substantial yet more radical in its critique. And precisely this radicality or thoroughness might be what is needed in addressing the challenges of globalisation’s broken promise, because it enables artists and cultural workers to contest the existing ways in which we map the world, and thus the dominant understanding of the international itself. In the case of the migration crisis, the violence at the European borders may not be due primarily to a lack of empathy or solidarity, but first and foremost to the oppressive discourses, narratives and procedures that fail to recognise the individual life of a migrant. Revitalising the ideal of cultural internationalisation might thus exist in an attempt to emancipate, as much as possible, the individual, the singular or the sensorial from its dominant discursive and conceptual context: an individual who is different, who is somewhere else, and whose fear of danger and hope of a better life will, to some extent, elude our conceptual understanding.

Literature

- Amnesty International (2018). ‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea. Europe fails in refugees and migrants in the central Mediterranean’.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony (2008). ‘Education for global citizenship’. In: Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. 107 (1): 83–99.

- Baldo, Sulamin (2017). ‘Border control from hell. How the EU’s migration partnership legitimizes Sudan’s militia state’. Washington: The enough project.

- Barbieri, Alberto et al. (2020). ‘The torture factory. Report on human rights violations against migrants and refugees in Libya (2014-2020)’. Rome: Medu.

- Boon, Errol (2019). 'What does cultural Internationalisation mean anno 2021?’. Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- Boon, Errol (2020a). ‘Translocality: artistic internationalisation after the corona crisis’. Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- Boon, Errol (2020b). ‘Beyond expats and nomads: on cosmopolitanism in the arts.’ Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- Bul, Maarten (2018). ‘Report on fair international cultural cooperation #1 – funding parties. Conventions and pratical issues in funding international activities’. Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- Chayka, Kyle (2019). ‘Can the Art World Kick Its Addiction to Flying?’ London: Frieze.

- Dasgupta (2019a). ‘The aesthetics of displacement: dissonance and dissensus in Adorno and Rancière’. In: Distributions of the Sensible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. 119-144.

- Dasgupta (2019b).’Fuocoammare and the aesthetic rendition of the relational experience of migration.’ In: Handbook of art and global migration. Berlin: De Gruyter. 102-116.

- Doorman, Maarten (2019). ‘Far-off and nearby - on translocality in the arts’. Amsterdam: Nieuw Dakota.

- Doorman, Maarten (2020). ‘On translocality in the arts’. Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- European Commission (2020). ‘New pact on migration and asylum.’

- Figes, Orlando (2019). Europeans: Three Lives and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture. London: Penguin Books.

- Government of The Netherlands (2020). ‘International Cultural Policy 2021-2024’.

- Graan, Mike de (2018). ‘Beyond Curiosity and Desire: Towards Fairer International Cooperation in the Arts’. Amsterdam: IETM, On the Move and Dutchculture.

- Hall, Stuart (1997). ‘The Local and the Global. Globalization and Ethnicity. In: Culture, Globalization and the World-System. Minneapolis.

- Human Rights Watch (2019). ‘European Union. Events of 2018.’

- Janssens, Joris (2018). ‘(Re)framing the International. On new ways of working internationally in the arts’. Brussel: Flanders Arts Institute.

- Polman, Linda (2020). ‘Tegen elke prijs’. Amsterdam: De Groene Amsterdammer.

- Smith, Laura; DeMeo, Brieahn & Widmann, Sunny (2011). ’Identity, Migration, and the Arts: Three Case Studies of Translocal Communities.’ In: The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society. Vol.41: 186-197.

- Vanackere, Annemie (2019). ‘From local spectator to international player’. Amsterdam: DutchCulture.

- Van Imschoot, Tom (2018). ‘De nood aan een andere taal’. Brussel: Kunstenpunt.